Home>“China is a country just like any other”

26.05.2015

“China is a country just like any other”

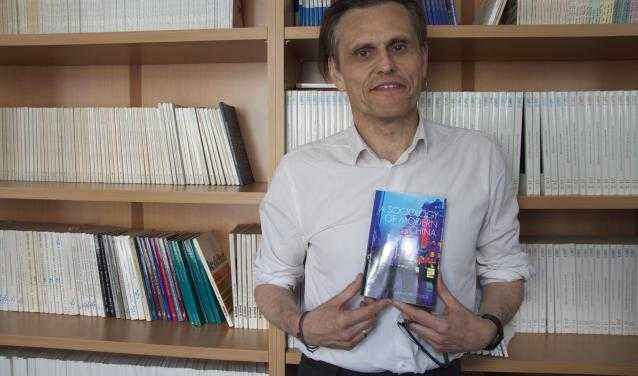

We met sociologist Jean-Louis Rocca on the publication of his new book, “A Sociology of Contemporary China”, Hurst & Co, first published in French in 2010, and largely augmented in this English version.

A professor at Sciences Po - CERI since 2011, Jean-Louis Rocca works on the evolution of political relations and social stratification in contemporary China. In his book, he uses the tools of social science to debunk persistent myths about China.

- Your book paints a nuanced portrait of China, far from the usual clichés. Why do we have trouble understanding China as a country ?

We have always had a specific image of China, positive or negative. For centuries we have perceived it as a country with a long history and a great civilization, but very different from us. In a way, we saw it as the “otherness of Europe”. But since the 1980's, two opposed images have emerged, one depicting the country as crippled by tradition and its totalitarian past and unable to change except in the economic domain, the other stressing the Chinese miracle with admiration. China doesn't leave anyone indifferent, it's hard to remain objective.

We don't strive to understand the country, but rather to have an opinion of it. It's not the same for India or Brazil, on which statements are far less driven by passion and ideology.

- What are the most common misconceptions about China that your book seeks to counter?

I'm mainly writing against two ideological currents that dominate the media and scholarship. On one hand there is the idea that China has to follow the path of modernization, that it has no choice but to progress on towards a free market, democracy and a social system based on the individual. The second is the idea that China has to follow its own path. That is has a certain kind of cultural, political, social system that prevents it from modernizing the way other countries do. It's the argument that it is impossible for the time being to establish a democratic system because the Chinese people don't have it in their blood: because they are supposed to emphasize collective interest to the detriment of individual interest and other “chinese values” that prevent them from really understanding the value of democracy.

- What's the main point that you make in this book ?

These two currents prevent us from seeing the country as it really is. My book tries to explore a different way. My main point is that China is a normal country, just like any other. Of course we have very different cultural ideas and realities, but Chinese people are just people, and their way to consider history or politics is not so different from ours. We have to use the tools of social science to study China as objectively as possible.

- Do the Chinese have as much trouble understanding us as we have understanding them?

It's probably even more difficult for them. We have images, common views, clichés and for scholars it's difficult to go against them. But the main difference is that in France, if you want to know what's “really” going on in China you can find the information. It's not the case in China. There is a real lack of specialists of western countries, there are no sociologists working on the “West” in China, they mainly focus on China itself.

- You describe the Chinese society, which arose at the end of the 1990s with the great reforms, as petrified by the fear of chaos and insecurity. Why is that so?

Indeed the Chinese are afraid of potential troubles that could endanger their social stability, as we have seen during the Hong Kong protests. The Chinese have experienced very troubled times. Until recently there has been political trouble every 4 or 5 years. Many people were killed, beaten, imprisoned. The Tian'anmen square movement in 1989 was a tragedy. So the Chinese have very bad memories of political change and periods of trouble. Additionally, from 1949 until the 1990s, criminality has been nearly non-existent. People didn't lock their doors! That's still considered the norm even though times have changed, so the Chinese remain very sensitive regarding any kind of insecurity.

- Yet you also describe the optimism reigning in the country...

Yes, and that's another reason why the Chinese are not eager for political change that could destabilize the country: most Chinese have reaped immense benefits from the reforms of the 1990's. Many people were poorly fed, had bad housing conditions and few to no opportunities in terms of personal achievement and jobs. In only 20 years they have become “middle class”, including the rural population. They now have access to leisure time, holidays, university, travel abroad...

- What will the next frontier of reforms be? The next challenges?

For me the next challenge is precisely to increase the size of the middle class. The social stratification of Chinese society has to change. Today we have very few rich people, most people are still at the bottom. The social structure cannot remain “pyramid”-like. China should aspire to have very few rich, very few poor and a large middle class. The issue is to know how to build up this kind of social stratification.

Interview by Andrea Palasciano.