Home>Indian Lessons

25.07.2019

Indian Lessons

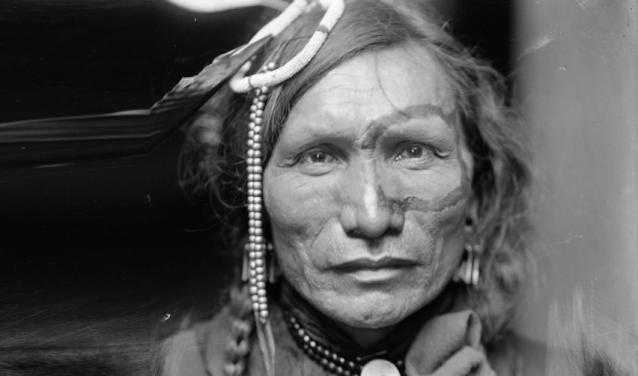

Louis Assier-Andrieu took his first steps in research alongside Claude Lévi-Strauss. As an anthropologist, and then historian, sociologist, and lawyer, he has long conducted field studies on the life of indigenous peoples: the Cheyenne, Inuits and Cajun in North America. His humanist observations have led him to a very particular understanding of the law. Explanations.

You have studied the rights of American Indians and Inuit people. What is special about them?

Louis Assier-Andrieu: What is special is that they don’t exist – or rather that they did not exist until the West introduced them. This is not a judgment but a fact. Let me explain: to claim a right involves proving that one has this right. Imagine asking Indian tribes to prove that a given mountain, river, or plain belongs to them. This is what they were asked to do in order to legally establish fishing and hunting areas reserved for them. They therefore needed to invent something that resembled laws.

How did they proceed?

L.A-A. : When one of the first cases emerged in 1979, in British Columbia, the Cheyenne used a lawyer who consulted an anthropologist to determine whether the Indians had landmarks to define their territories. He wanted something factual and tangible that was rational. It was the only way of dialoging with the law, which requires limits between the self and one’s property. In reality, the Indians consider their “ownership” of this land to be granted to them from divinities, and they do not believe they should have to prove or frame it. This is legal anthropology: reconciling a society’s organizational rules with the law , which is a purely Western creation that has imposed itself as a universal mechanism.

But how, without laws, do these societies resolve other types of conflicts?

L.A-A. : They do it through practices and rites that seek to eliminate conflicts rather than to condemn on the basis of evidence and arguments. For example, if the member of an Inuit tribe is accused of violating a member of another tribe, the two tribes organize a singing duel. They start by taking turns chanting in their own way. Over time, their chants mix. When they reach unison, the conflict is resolved. This is an irrational approach that is far removed from the law. The Cheyenne similarly regulate the worst infraction to their customs: when one of their members refuses to fulfill his role during the hunt. The sanction applied – the harshest of all – is a two-month ban. However, the sanction may be lifted if the offender’s family organizes a party and invites the whole tribe to it.

Yet you say that the Indians have developed their own law…

L.A-A.: Absolutely. And I can tell you that they use it! They have ended up appropriating the law we imposed on them. There are many North American Indian lawyers today. For the current Indian nation, recognition of its specific rights involves harnessing to its benefit a Western law that is blind to the mythological layers of Indian culture. Since the law creates its own legitimacy, it can only be fought from the inside. Vine Deloria Jr., a “native-American” from the Lakota tribe, paved the way in the 1970s. An activist, writer, theologian, and historian, he ended up teaching the law that he considered as the best way to lead his struggle. Today, indigenous communities use the law for some pretty surprising purposes: for example, they are seeking to collect fees from scientists who study their mores and territories. They are also looking to charge fees on courses about them. In a way, the West is being hoisted with its own petard as the indigenous haggle over what they have left after being deprived of their property.

What conclusions can we draw from these observations?

L.A-A.: A legal anthropological approach can help better understand the nature of the law. We can see it emerge by contrast. We can then see how it differs from rules and norms established according to different logics. A key point is that the law is a self-justifying system. It is an implacable force, and this explains its proliferation to all societies, especially with the establishment of universal rights. It is important to recall, for example, that private property in the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen is part of the quartet of natural and inalienable rights. The three others are freedom, safety, and resistance to oppression.

Interview by Hélène Naudet, office of the VP for Research.

This article was originally published in Cogito, the research newsletter. Read the original article and consult the bibliography here.

CNRS research director in legal science at Sciences Po’s Law School, Louis Assier-Andrieu focuses on the historical anthropology of Western law, the cultural theory of law, legal and cultural norms, and “tribe” law, its culture, its history and its evolution. A professor at Sciences Po, he has also taught in many institutions in France (École Nationale de la Magistrature, École des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales) and abroad (Yale, Tulane, Cornell, Bonn, Barcelona…)

More information