Home>The Pakistan Paradox, Instability and Resilience

14.07.2015

The Pakistan Paradox, Instability and Resilience

Pakistan has been racked by numerous tensions since its creation in 1947, yet it has managed not only to preserve its unity but to establish itself as a major player in the region. Christophe Jaffrelot,* CERI researcher and professor at Sciences Po, analyses this surprising endurance in his new book, The Pakistan Paradox, Instability and Resilience, published simultaneously in the USA, India and the UK.** We asked the author a few questions about this complex country.

- What is the place of religion, and Islam specifically, in Pakistan?

Christophe Jaffrelot: In 1947 there was a fundamental tension between those who wanted Pakistan to be a country for the Muslim community of colonial India, yet without making it a theocracy, and those who wanted an Islamic state and the application of sharia law. For a long time, the former position, a legacy of the country’s founding father Mohammad Ali Jinnah, prevailed. But in the 1970s, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto challenged this tradition and sought to instrumentalize religion for political ends, legitimizing a repertoire hostile to religious minorities in the public sphere. Under the rule of General Zia, this shift took a militant turn. Islamization became state policy, concerning everything from law to taxation and education. Not to mention covert support to the jihadists active in Afghanistan and later in Kashmir, two areas where the Pakistani Army sought to play a role through Islamist intermediaries.

- One of the prime issues for a developing state is education. In your book, you describe Pakistan’s significant weakness in this area. What are the difficulties that prevent an effective national education system being put in place?

C.J.: There is a glaring lack of public investment in education; the budgets are ridiculous. This reflects a societal imbalance, as the elite has never considered that the masses should have access to education – which, moreover, was also long the case in India. This elite has also never considered that it should have to pay taxes and each successive regime, both civilian and military, has systematically spared it from doing so. As such, the state effectively does not have the means for a real education or health policy. The result is a multi-tiered education system; at one end of the spectrum are very expensive private schools, and at the other are the Koranic schools, which provide an education for a very modest cost. However, the desire for education remains very strong among the working and middle classes and, in response, we are seeing the development of private schools and universities of a remarkably high standard.

- How does the situation stand for women in Pakistan?

C.J.: It is very mixed. Many women live in very difficult conditions, but this is as much for cultural as for social reasons and it is important to avoid any clichés. Most women are not subjected to what in the West we call the full veil. There are also some women holding leadership positions in politics, the judiciary, NGOs and the media. The first Indo-Pakistani war was triggered in 1947 following Kashmir’s choice to join India.

- Can this not be seen as a pretext for Pakistan and India to go to war rather than a real desire for Kashmir?

C.J.: It has become a pretext to some extent for the Pakistani military, in that as long as the Kashmir issue is unresolved, they have a good reason to benefit from a large budget to fight India. The Pakistani army therefore has little incentive to settle the issue of Kashmir. From the Indian perspective, the area is highly sensitive as it borders with China, an ally of Pakistan. However, as India’s largest trade partner, China does not want to alienate India and tends to try and pacify relations.

- What are the advantages of the alliance between China and Pakistan?

C.J.: For the Chinese, helping Pakistan forces India to look to the West, whereas India would like to expand its influence in South East Asia. By joining forces with Islamabad, Beijing also gains access via the Karrakorum Highway (which crosses the Himalayas at about 4,000m) to the Indian Ocean – where, moreover, the Chinese have built a deep-sea port in Gwadar (Pakistani Balochistan) to complete their “pearl necklace” of ports from the South China Sea to the Persian Gulf. For Pakistan, the relationship with China is essential, not least because China sells it weapons, supports it at the UN and invests in its infrastructure. But Pakistan and China have no ideological affinity, in fact rather the opposite. Indeed, Pakistan’s Islamic identity is a problem for some Chinese who are concerned about the links that Uighur Islamists have with Islamists based on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border.

- Pakistan is one of the “next eleven” promising economies identified by US bank Goldman Sachs. Do you agree that it deserves this status?

C.J.: What may hold Pakistan back are key variables related to political instability (Baluchistan is beset by what is almost a war of independence, the conflict between Sunni and Shiite groups is worsening, while Karachi, the lifeblood of the economy, lurches from crisis to crisis). In addition, Pakistan faces huge environmental problems (water scarcity is a major issue) and demographic challenges (the transition is far from complete on this point). Moreover, Pakistan has very few natural resources and is kept afloat financially by foreign powers and the IMF. US subsidies to Pakistan came to over thirty billion dollars between 2001 and 2014. It’s a vicious circle; as long as it is being kept afloat, Pakistan carries out no tax reforms, so does not free up any resources to develop its infrastructure and its education system. Nonetheless, Pakistan does have its strengths: a population of nearly 200 million people, a military strike force unparalleled in the Muslim world because of its nuclear capability, and highly enterprising economic and intellectual elites (which can be seen in the Gulf, although they are far outnumbered there by the millions of unqualified young Pakistani workers).

- In the end, can it be said that Pakistan is a country built on the threat from India? Is it possible for relations to improve?

C.J.: It is a country largely built in opposition to its neighbour and the neighbouring Hindu majority – hence Partition and the defensive nature of the Pakistani state. Fear (hate?) of the Other has bolstered the army’s security-based arguments and favoured centralization of the state. One wonders whether a detente with India would be enough to reverse the trend. There are now so many entrenched positions based on the “Indian threat” that even if this threat appeared to weaken, the army would probably find a reason to perpetuate the conflict. After all, it is this struggle that justifies its status and so much of its funding. Democratic developments can certainly come from judges, media or NGOs, but these parts of civil society are currently no match for the military. The military succeeds in ruling from behind the scenes without having to govern – that thankless task is left to politicians who content themselves with managing day-to-day affairs.

* Christophe Jaffrelot is one of world’s leading specialists on South Asia. Besides his work at Sciences Po, he is a visiting professor at the King’s India Institute (London) and Global Scholar at Princeton. He is also involved in many publishing and consulting activities in France and abroad. Find out more.

** This is an updated translation of Syndrome Pakistanais (Fr), published in 2013 in the CERI-Sciences Po collection by Fayard and winner of the Prix Brienne. This edition is published by Hurst (London) in the CERI-Sciences Po collection, by Oxford University Press (New York) and by Random House (New Delhi).

Interview by Mathilde Jove

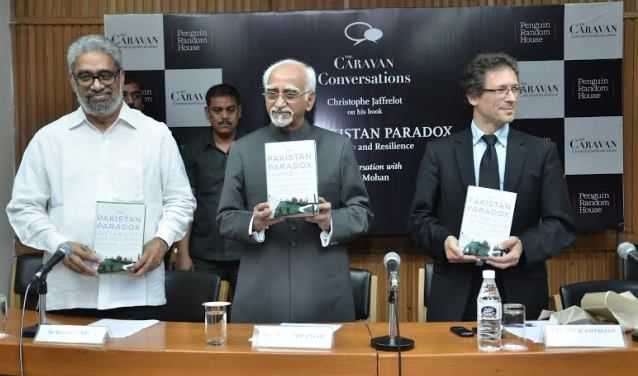

Photo: the book launch of the South Asian edition, which took place in Delhi on the 4th of June, under the chairmanship of Vice President Hamid Ansari (centre), has been the occasion of a conversation between the author and Prof. Raja Mohan (left), Senior Research fellow at the Observatory Research Foundation, a partner of Sciences Po.