Home>Research>SAFEDUC Research Project >Student Exposure to Gender-Based and Sexual Violence: SAFEDUC 2024 Survey Results

Student Exposure to Gender-Based and Sexual Violence: SAFEDUC 2024 Survey Results

In 2024, students enrolled at Universit�é Paris Cité and Sciences Po were invited to take part in a questionnaire survey aimed at measuring the prevalence of gender-based and sexual violence (GBSV) within the student population. The survey sought to document the acts of violence experienced, the contexts in which they occurred, and to provide an overview of the number and types of violence reported. This report presents the first results of the survey

Virginie Bonnot (Cité du Genre, LPS-UPCité) and Hélène Périvier (PRESAGE-Sciences Po) led this project and coordinated it alongside Victor Coutolleau (PRESAGE-Sciences Po), Marta Domínguez Folgueras (CRIS-Sciences Po), Joëlle Kivits (ECEVE-UPCité), Clara Le Gallic-Ach (Ined - CRIS-Sciences Po), and Violette Toye (PRESAGE-Sciences Po).

Table of Contents

Why a New Survey on Gender-Based and Sexual Violence?

Background to the Survey

In line with major prevalence studies on gender-based and sexual violence (GBSV) in the general population (Bozon 1995, 2012; Jaspard and Enveff team, 2001), research has shown that this type of violence takes specific forms within universities. Indeed, the higher education and research (HER) sector is characterised by economic, gender, age, class, and hierarchical dynamics that differ from those observed in the workplace or society at large (Cardi, Naudier, and Pruvost 2005). These particularities call for specific approaches to better understand these phenomena and to develop appropriate measures to combat GBSV.

The university-focused component of the Violence et Rapports de Genre (Virage) survey (Ined, 2015) provided insight into the extent of such violence across four higher education institutions (Brown et al. 2020; Lebugle, Dupuis, and the Virage survey team, 2018). As the primary scientific source on the prevalence of violence in the general population, these 2015 data remained for a long time the only reference specifically concerning students. More recently, initiatives have emerged at both national (Observatoire des VSS dans l’enseignement supérieur (FR)) and local levels, led by universities (Nantes Université (FR), Université de Clermont-Auvergne (FR), École Polytechnique (FR)) or student associations (Ça pèse à Centrale Supélec (FR)). These studies have shown that such violence primarily affects female students and gender minorities, negatively impacting their learning conditions, social lives, and health. In turn, this may have long-term consequences for their professional trajectories.

Specificities of the SAFEDUC Project

The SAFEDUC survey is part of a broader collective effort to quantify gender-based and sexual violence (GBSV) in higher education. Funded by the Initiative d’Excellence Université Paris 2019 (IdEx UP19) and led by Sciences Po's Gender Studies Programme, this research project has also received support from the Cité du Genre at Université Paris Cité (UPCité)1. It has been carried out by a multidisciplinary research team from the two partner institutions. Based on a rigorous methodology, the survey offers a reproducible research protocol that can be applied in other institutions for comparative purposes. Its findings aim to help higher education and research institutions, the student population, and, more broadly, public authorities to grasp the scale of the phenomenon. The results can contribute to the development of institutional policies tailored to combating this form of violence.

This report provides an initial overview of the prevalence of GBSV among the student populations of the two partner institutions. The survey covers violence occurring in the context of student life, encompassing everything from classrooms to internships and parallel professional activities, as well as sports events and private gatherings. It provides valuable data not only on the prevalence of this form of violence but also on the circumstances in which it arises, the profiles of perpetrators, and its consequences.

Our findings are consistent with those of other comparable studies: gender-based and sexual violence primarily affects women as well as gender and sexual minorities. It negatively impacts students’ living and study conditions and, in doing so, undermines equal opportunities in both academic and professional trajectories. Through its dissemination and the additional analyses that will emerge from it, this survey is set to contribute to a broader movement of awareness-raising regarding both the scale and specific characteristics of gender-based and sexual violence affecting the student population.

Points of Attention

The survey was conducted from mid-March to mid-May 2024, gathering 4,649 complete responses, as well as 901 partially filled questionnaires. The overall participation rate stands at 8.1%, with a significant disparity between the two institutions: approximately 20% at Sciences Po (n = 2,958) and 5% at UPCité (n = 2,592). Within each institution, the response rate varies by programme, year, etc. A detailed summary of the methodology and survey process is provided in a dedicated article, in which we outline the sampling biases inherent in this type of survey and suggest potential solutions to mitigate them, at least partially (WP survey process).

The sociodemographic composition of the respondent sample differs from that of the student population at each institution, notably with an overrepresentation of women, children from managerial and higher intellectual professions, as well as scholarship students. To correct for these biases and improve the sample's representativeness, a weighting variable was created based on available data on the student populations of both institutions2.

A representativeness bias remains related to the low response rate typical of this type of survey, specifically regarding victims of GBSV. Specifically, individuals who have not experienced GBSV may be less likely to respond, as they do not feel directly affected by the issue, which may result in an overestimation of the prevalence. Conversely, victims may be reluctant to respond for fear of reliving painful memories or concerns about the loss of anonymity, leading to an underestimation of the prevalence rate. These biases cannot be fully corrected, and as such, we present three rates: a minimum prevalence rate, an adjusted (or “weighted”) rate, and a raw rate.

- The minimum rate is calculated by comparing the number of individuals reporting having experienced an act of violence in the survey to the entire student population. This assumes that all victims responded to the survey, which is not the case, so this rate is not credible. However, the actual prevalence rate can never be lower than this figure.

- The raw rate refers to the number of people reporting having experienced an act of violence, relative to all respondents. This assumes the sample is representative of the general population in terms of standard characteristics (gender, social background, year and field of study, etc.), but also with regard to violence. This is not the case; however, this rate represents the exact proportion of victims among those who participated in the survey.

- The weighted prevalence rate is calculated based on the weighted adjusted figures, that is, those for which representativeness biases have been partially corrected with regard to certain characteristics (such as gender, social background, year, and field of study, etc.). The rate is calculated within the respondent population, similar to the raw rate. It more accurately represents the student populations of the two institutions with regard to the characteristics that have been corrected for. Since experiencing GBSV correlates with certain characteristics, including gender, this weighted rate partially corrects for the reporting bias regarding GBSV.

The statistical analysis presented in this report was carried out using the complete questionnaires, i.e., 4,649 responses. The profile of individuals who chose not to complete the questionnaire has been analysed in a working paper dedicated to the analysis of the survey process (Coutolleau, Le Gallic-Ach, and Périvier (2025)).

Prevalence of Different Categories of Violence

Types of Violence Measured in the Survey

Victimisation surveys, conducted using survey methods, complement our understanding of a social phenomenon that is most often measured through administrative data. They are the most suitable tool for characterising and measuring the violence experienced by victims, as the questions are phrased in such a way that respondents recognise their experiences in the descriptions of gender-based and sexual violence (GBSV) without requiring legal knowledge. Thus, the questions do not merely rely on the legal definition of the acts but cover a broad range of situations, describing them in precise and concrete terms.

The SAFEDUC adopts the broad definition of gender-based violence set out by the Istanbul Convention3 and by a body of literature showing that verbal, economic, physical, and sexual violence overlap within a system of multiple victimisation. Documenting all these dimensions allows us to capture both the emergence of violence and its consequences.

To achieve this level of precision, the questionnaire must include a large number of questions. The SAFEDUC questionnaire asked respondents whether, during their studies4, they had been exposed to 14 acts of violence, ranging from mockery to incidents that could be classified as sexual assaults, rapes, or attempted rapes. To ensure comparability with other studies, the 14 acts and their formulations were similar to those measured in the Virage Universités surveys and, more recently, in the Nantes Université survey5. Additionally, questions regarding the context of these acts were directed to individuals who reported experiencing violence during the last 12 months.

To provide an overview of the survey findings, the acts of violence were grouped into four categories: psychological or social violations includes acts of violence that do not necessarily have a sexual dimension (mockery, exclusion from collective activities, etc.). Sexual harassment corresponds to acts of violence that are sexual in nature but do not directly involve physical contact (sexual gestures, being followed, exposure to exhibitionism). Physical or sexual assaults refers to acts of physical or sexual violence involving contact: groping, administering substances without the victim's knowledge, or exerting serious pressure to obtain sexual favours. The fourth category focuses on acts that could be classified as rape or attempted rape6. The details of the questions and classification are summarised in Note 1.

In this context, comparisons with other surveys should be approached with caution: the more acts of violence considered by the survey, the more likely it is that students have been victims of them. Comparisons with other surveys are only relevant when based on specific acts of violence, with identical or similar formulations, or when using categories that group together the same acts.

Note 1: Categorisation of Acts of Violence

- Has anyone subjected you to mockery or degrading or humiliating comments (e.g. remarks about your appearance or body)?

- Has anyone deliberately excluded you from student, group or festive activities?

- Has anyone appropriated or destroyed your work, or forced you to do their work for them (an assignment, essay, portfolio, dissertation, presentation, etc.)?

- Has anyone damaged your reputation or tried to do so, by spreading rumours for example?

- Has anyone damaged your image or threatened to do so (by circulating intimate videos or photos, photos taken without your knowledge, photo montage, etc.)?

- Has someone made remarks or gestures of a sexual nature to you that made you feel uncomfortable (miming a sexual gesture, making sexual propositions, commenting on your sex life, etc.)?

- Were you forced to look at pornographic images that made you feel uncomfortable (on a group chat or unsolicited intimate photos, for example)?

- Has someone followed you, or contacted or approached so insistently that you felt uncomfortable or frightened?

- Did you encounter an exhibitionist or a voyeur?

- Has someone thrown an object at you with the intention of hurting you, pushed you, shaken you roughly or hit you?

- Has someone given you a substance (e.g., an addictive or medicinal drug) without your knowledge that was likely to impair your judgement or control over your actions?

- Has someone touched your bottom, kissed you or rubbed up against you even though you didn’t want to, or forced you to touch or be touched on your/their private parts?

- Has someone put you under serious pressure to obtain a sexual act from you; you were made to fear reprisals if you refused to comply with a sexual request; or you were given to understand that you might be rewarded if you complied with a sexual request?

Has someone tried or managed to have sexual intercourse with you, whether this involved penetration (with a penis, fingers or an object) or oral-genital contact, even though you didn’t want to?

Prevalence Rates

The prevalence rates measured for the four categories of violence are first presented in a summary form, based on the raw figures in Table 1. Individuals who reported experiencing violence in the last 12 months are included in the figures used to calculate the prevalence rate since the beginning of their higher education. 8.6% of respondents report having experienced at least one instance of rape or attempted rape since the start of their higher education, 28.4% report having experienced at least one occurence of “physical or sexual assault”, 50.3% report having experienced at least one incident of “sexual harassment” and 40.6% report having experienced at least one incident of “psychological or social violation”.

Table 1: Raw Prevalence Rates for Different Categories of Violence

| Since entering higher education | Over the past 12 months | |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological or social violation | 40.6 | 21.5 |

| Sexual harassment | 50.3 | 29.9 |

| Physical or sexual assault | 28.4 | 13.6 |

| Rape or attempted rape | 8.6 | 2.7 |

| Source: SAFEDUC (UPCité & Sciences Po, 2024). | ||

| Coverage: Student population of Sciences Po and Université Paris Cité in initial education or apprenticeship. | ||

| Reading: 40.6 % of Université Paris Cité and Sciences Po students report having experienced at least one psychological of social violation since starting higher education. | ||

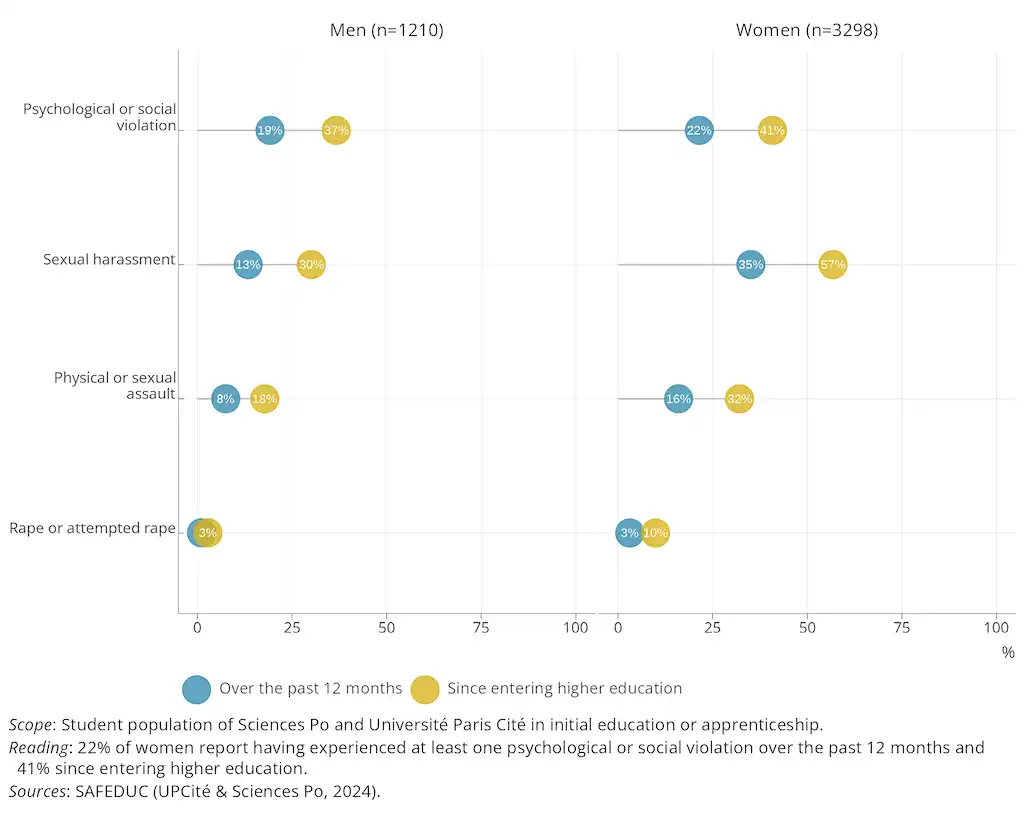

The weighted prevalence rates are broken down by gender category for the two time periods measured by the survey in Figure 1. This figure includes only men and women7. The raw prevalence rates affecting non-binary respondents or those preferring another term to define themselves are presented further down (Table 2).

Figure 1: Weighted Prevalence Rates for Different Categories of Violence by Gender (excluding non-binary individuals or those using another term)

Consistent with the findings of other surveys cited, women are disproportionately exposed to gender-based and sexual violence. While women and men report psychological or social violations at relatively similar rates, both in the past 12 months (19% of male respondents compared to 22% of female respondents) and since the start of their higher education (41% of women compared to 37% of men)8, the gap between the two categories widens as the violence takes on a sexual dimension. Indeed, female students are more likely to report incidents of sexual harassment than psychological or social violations: over half of the female respondents (57%) report having experienced sexual harassment since the start of their studies, whereas a minority of male respondents report the same (30%)9.

This gap is also evident in cases of physical or sexual assault10, as well as in instances of rape or attempted rape: one in ten female students reports having experienced such incidents since the start of their higher education, compared to only 3% of men11.

These estimates highlight the high prevalence of gender-based and sexual violence in student life and the over-representation of women among the victims. A significant proportion of respondents report having been exposed to violence since the start of their higher education, as well as in the 12 months preceding the survey.

The prevalence rates are substantially the same whether calculated based on weighted data or raw data (Table 2). The prevalence rates reported by non-binary individuals or those who prefer another term should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size (n=141). However, it is noteworthy that individuals in this gender category report experiencing violence at similar rates to women over the past 12 months and report higher rates since the start of their higher education. Non-binary individuals or those who identify otherwise thus appear to be, like women, disproportionately exposed to violence during their student life when compared to men12. Furthermore, non-binary individuals or those preferring another term report significantly more frequently than women that they have experienced psychological or social violations since the start of their higher education13.

Table 2: Estimation of the prevalence rate for different categories of violent acts by gender

|

Women (n=3298)

|

Men (n=1210)

|

Non binary, use another term (n=141)

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min. rate1 |

Estimation

| Min. rate1 |

Estimation

| Min. rate |

Estimation

| ||||

| Wtd. rate2 | Raw rate3 | Wtd. rate2 | Raw rate3 | Wtd. rate | Raw rate3 | ||||

| Psychological or social violation | |||||||||

| Since entering higher education | 3.0 | 40.8 | 41.2 | 1.9 | 36.7 | 37.0 | - | - | 56.7 |

| Incl. over the past 12 months | 1.6 | 21.5 | 22.0 | 1.0 | 19.2 | 19.6 | - | - | 25.5 |

| Sexual harassment | |||||||||

| Since entering higher education | 4.1 | 56.8 | 56.8 | 1.6 | 30.1 | 31.0 | - | - | 63.8 |

| Incl. over the past 12 months | 2.6 | 35.1 | 35.7 | 0.7 | 13.4 | 14.0 | - | - | 32.6 |

| Physical or sexual assault | |||||||||

| Since entering higher education | 2.3 | 32.1 | 31.9 | 0.9 | 17.8 | 17.8 | - | - | 36.9 |

| Incl. over the past 12 months | 1.2 | 16.0 | 15.8 | 0.4 | 7.5 | 7.6 | - | - | 15.6 |

| Rape or attempted rape | |||||||||

| Since entering higher education | 0.8 | 9.9 | 10.3 | 0.2 | 2.9 | 3.4 | - | - | 12.8 |

| Incl. over the past 12 months | 0.2 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | - | - | 3.5 |

| Source: SAFEDUC (UPCité & Sciences Po, 2024). | |||||||||

| Scope: Student population of Sciences Po and Université Paris Cité in initial education or apprenticeship. | |||||||||

| Reading: 3.2 % of female students who took part in the survey report having experienced a rape or attempted rape over the 12 past months. | |||||||||

| 1 Minimum rates are given for information purposes only, they are based on the implausible hypothesis that all gender-based violence victims responded to the survey. | |||||||||

| 2 Weighted rates are calculated based on the weighted sample. | |||||||||

| 3 Raw rates refers to the number of people reporting having experienced an act of violence, relative to all respondents. | |||||||||

Prevalence of GBSV Over the Last 12 Months

One of the unique aspects of the SAFEDUC survey lies in its simultaneous deployment across two higher education institutions, allowing for a comparison of prevalence rates between these two populations. The temporal reference point of the start of higher education is not relevant, as it encompasses transitions between different institutions.

It is observed that the differences in prevalence rates measured for the past 12 months14 are not statistically significant (Table 3). The rates observed in SAFEDUC are comparable to those from recent, similar surveys. This convergence of results provides an estimate of the prevalence of different categories of violence. The prevalence rate for rape and attempted rape over the past 12 months ranges from 2 to 3%15, while the rate for groping is approximately 10%16. All forms of violence are widespread within student life, with women and gender and sexual minorities being disproportionately affected, although other factors also contribute to victimisation.

Table 3: Weighted Prevalence Rates of Violence Experienced in the Last 12 Months by Institution

| Sciences Po | UPCité | Diff.1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological or social violation | 21.1 | 20.1 | ns |

| Sexual harassment | 27.2 | 27.8 | ns |

| Physical or sexual assault | 14.1 | 11.8 | ns |

| Viol ou tentative de viol | 2.6 | 2.2 | ns |

| Sample size | 2556 | 2093 | - |

| Source: SAFEDUC (UPCité & Sciences Po, 2024). | |||

| Scope: Student population of Sciences Po and Université Paris Cité in initial education or apprenticeship. | |||

| Reading: 2.2 % of Université Paris Cité students reported having experienced rape or attempted rape at least once over the 12 past months. | |||

| 1 Chi-squared test applied to raw counts ; ns = not significant at 5 % level. | |||

Risk Factors

The likelihood of reporting incidents of violence is strongly influenced by gender. The SAFEDUC survey also highlights other risk factors such as self-declared sexual orientation and paid employment.

The Impact of Sexual Orientation

The questionnaire includes a question on self-declared sexual orientation. Significant differences are observed between non-heterosexual and heterosexual individuals (Table 4). Consistent with other surveys (Mellins et al. 2017), the former report experiencing violence more frequently than the latter. Thus, for all four categories of violence, gay, bisexual, or individuals identifying with another term are more likely to report incidents of violence than heterosexual men, both in the last 12 months and since the start of their higher education studies17. The same pattern is observed for lesbian, bisexual, or individuals identifying with another term compared to women who identify as heterosexual18.

Table 4: Weighted Prevalence Rates of Different Categories of Violence by Self-Declared Sexual Orientation

|

Women

|

Men

| |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not heterosexual (n=1102) | Heterosexual (n=2005) | Not Héterosexual (n=301) | Heterosexual (n=853) | |

| Psychological or social violation | ||||

| Since entering higher education | 46.3 | 38.8 | 46.0 | 33.2 |

| Incl. over the past 12 months | 26.0 | 19.7 | 25.1 | 17.1 |

| Sexual harassment | ||||

| Since entering higher education | 63.1 | 54.6 | 44.7 | 24.6 |

| Incl. over the past 12 months | 42.3 | 32.1 | 23.6 | 9.5 |

| Physical or sexual assault | ||||

| Since entering higher education | 39.5 | 29.3 | 30.0 | 14.1 |

| Incl. over the past 12 months | 19.6 | 14.7 | 13.3 | 5.8 |

| Rape or attempted rape | ||||

| Since entering higher education | 13.8 | 8.3 | 9.1 | 0.9 |

| Incl. over the past 12 months | 5.0 | 2.3 | 3.7 | 0.4 |

| Source: SAFEDUC (UPCité & Sciences Po, 2024). | ||||

| Scope: Student population of Sciences Po and Université Paris Cité in initial education or apprenticeship. | ||||

| Reading: 38.8% of female students identifying as heterosexual report having experienced at least one psychological or social violation since entering higher education. | ||||

Non-heterosexual men report experiencing psychological or social violations more frequently than heterosexual women, whereas the latter are more likely to report experiencing sexual harassment. This is likely due to a distinction between psychological or verbal violence specifically targeting men who deviate from the heterosexual norm and sexually motivated psychological violence that predominantly affects women. Heterosexual men stand out as the group least exposed to violence compared to the other three groups.

Paid Employment as a Risk Factor

Another factor associated with victimisation identified in the SAFEDUC survey is engaging in paid employment over the past 12 months, as well as the degree of material dependence on this activity (Table 5).

Table 5: Weighted Prevalence Rates of Different Categories of Violence in the Past 12 Months by Employment Status

|

Not involved in paid work (n=1285)

|

Involved in paid work

| ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Not very important or not important at all (n=1811) | Essential or very important (n=1455) | ||

| Psychological or social violation | |||

| Since entering higher education | 32.4 | 36.7 | 48.4 |

| Incl. over the past 12 months | 17.8 | 20.3 | 23.8 |

| Sexual harassment | |||

| Since entering higher education | 37.5 | 45.6 | 58.3 |

| Incl. over the past 12 months | 23.0 | 27.3 | 32.1 |

| Physical or sexual assault | |||

| Since entering higher education | 18.5 | 25.2 | 36.8 |

| Incl. over the past 12 months | 10.1 | 13.5 | 15.6 |

| Rape or attempted rape | |||

| Since entering higher education | 5.2 | 6.9 | 9.9 |

| Incl. over the past 12 months | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.3 |

| Source: SAFEDUC (UPCité & Sciences Po, 2024). | |||

| Scope: Student population of Sciences Po and Université Paris Cité in initial education or apprenticeship. | |||

| Reading: 32.4 % of students not involved in paid work over the past 12 months report having experienced at least one psychological or social violation since entering higher education. | |||

The more respondents describe paid employment as "essential for living,"19 the more likely they are to report experiences of violence. This trend is observed across all forms of violence since the beginning of higher education and over the past 12 months for the first three categories of incidents.

Several hypotheses may explain this pattern. Firstly, being present in a workplace setting may increase exposure to environments where violence can occur, thereby amplifying the risk of victimisation. Additionally, engaging in paid work and reliance on this income may be indicative of financial insecurity, which could render individuals particularly vulnerable. The survey findings suggest that students who are financially dependent on paid employment constitute a high-risk group in terms of experiencing gender-based and sexual violence during their time in higher education.

In What Contexts Do These Forms of Violence Occur?

To clarify the concept of the student environment, the questionnaire included the following explanation: This may refer to incidents that took place within your institution but also outside of it, for example, during an internship, an apprenticeship, or within your student social life (friendships, romantic relationships, etc.). In order to provide context for the reported incidents of violence, the questionnaire included specific modules designed to contextualise experiences of violence that occurred within the past 12 months.

Where?

The questions regarding the locations where respondents experienced violence included 20 possible responses, which have been grouped into five categories:

- Institutional premises (classrooms, common areas, etc.)

- Events organised by the institution or its associations (sports events, student association activities, institutional events)

- Private settings (student gatherings, weekends away, private homes, vehicles, online, etc.)

- Professional settings (internships, apprenticeships, student jobs, research fieldwork, etc.)

- Other locations (public spaces, or locations categorised as "Other")

Table 6: Locations where incidents of violence occurred in the past 12 months (multiple locations possible for a single incident)

| On campus | At a university event | Private context | Work environment | Other | Total | Size (places) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological or social violation | 32.6 | 10.6 | 35.2 | 8.9 | 12.7 | 100 | 1853 |

| Sexual harassment | 19.4 | 2.8 | 31.2 | 10.2 | 36.2 | 100 | 1476 |

| Physical or sexual assault | 11.3 | 6.3 | 41.6 | 4.9 | 35.9 | 100 | 635 |

| Rape or attempted rape | 0.8 | 1.6 | 84.8 | 1.6 | 11.2 | 100 | 125 |

| Source: SAFEDUC (UPCité & Sciences Po, 2024). | |||||||

| Scope: Students at Sciences Po and Université Paris Cité in initial education or apprenticeship who reported experiencing at least one act of violence in the past 12 months. | |||||||

| Reading: 32.6% of the places where students said they experienced a form of psychological or social violation in the past 12 months are on campus. | |||||||

The private sphere is overrepresented among the locations where reported acts of violence have occurred. However, variations exist depending on the category of violence. 85% of reported rapes and attempted rapes took place in this setting, including 70% in the victim’s or perpetrator’s home or car. Incidents involving physical and sexual assaults occur across all contexts: 11.3% of reported cases took place within the institution, 6.3% at an institution-related event, and 5% in a professional setting. Personal violations and harassment (categories 1 and 2 of violent acts) frequently occur in academic contexts, with 43.2% of psychological or social violations taking place in such settings (32.6% within the institution and 10.6% at university-related events) and 22.2% of sexual harassment acts occurring in similar contexts (19.4% within the institution, 2.8% at university-related events). The professional setting, which includes internships and other placements directly linked to students’ training, must also be considered, as it accounts for 10.2% of personal violations with a sexual dimension.

The "Other" category, which primarily includes public spaces, is frequently cited in cases of sexual harassment and physical or sexual assaults (36.2%). Additionally, an analysis of the status of the perpetrators (examined further below) in incidents occurring in these "other settings" suggests that the perpetrators are not necessarily strangers. For instance, nearly 70% of psychological or social violations that occurred in these "other locations" were committed by fellow students.

Profile of Perpetrators

After identifying the location(s) where incidents of violence occurred in the 12 months preceding the survey, respondents answered a series of questions regarding the perpetrators. These included the perpetrators’ gender and number, their status within or outside the university (e.g., student, lecturer, colleague), and their prior relationship with the victim (e.g., friendship, intimate relationship, date, acquaintance).

Predominantly Male Perpetrators Acting Individually

Consistent with findings from most other studies, the available data on perpetrators of violence indicate that they are, in the majority of cases, men acting alone. This general profile is further specified according to the type of violence reported (Table 7).

Table 7: Gender and Number of Perpetrators by Category of Violence (Past 12 Months)

|

Lone perpetrator

|

Perpetrators in group

| Total | Size (perpetrators) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A woman | A man | Several women | Several men | Several men and women | |||

| Psychological or social violation | 23.7 | 37.6 | 11.5 | 9.9 | 17.2 | 100 | 1143 |

| Sexual harassment | 6.6 | 72.1 | 1.4 | 16.1 | 3.8 | 100 | 1206 |

| Physical or sexual assault | 9.5 | 79.8 | 0.8 | 8.5 | 1.4 | 100 | 516 |

| Rape or attempted rape | 5.7 | 88.6 | 1.0 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 100 | 105 |

| Source: SAFEDUC (UPCité & Sciences Po, 2024). | |||||||

| Scope: Students at Sciences Po and Université Paris Cité in initial education or apprenticeship who reported experiencing at least one act of violence in the past 12 months. | |||||||

| Reading: 23.7 % of reported perpetrators of psychological or social violations were lone women. | |||||||

Psychological or social violation involves a significant proportion of women and mixed-gender groups among the perpetrators, although men acting alone remain the most frequently cited (37.3%). The perpetrators identified for the other three categories of violence are, in the vast majority of cases, men acting alone: they account for 71.8% of the perpetrators of personal acts with a sexual dimension, 79.4% of perpetrators of physical or sexual integrity violations, and 88.6% of perpetrators of rape or attempted rape (Table 7).

Men in groups are also frequently cited as perpetrators in cases of sexual harassment (16%), in cases of physical or sexual assault (8.5%), and, to a lesser extent, in incidents of rape or attempted rape (4.8%). Regardless of their number, men represent 93.3% of the perpetrators cited for rape or attempted rape.

The Status of Perpetrators

The question regarding the status of perpetrators helps to identify members of the university, professional relationships, as well as any potential power dynamics between the individual reporting the violence and the perpetrators.

The questionnaire provided 12 different statuses, which were grouped into 3 categories: relationships within the university, work or internship relationships, and other relationships (outside of academic and professional contexts). The main statuses of perpetrators are presented, by type of violence, in Table 8.

Table 8: Status (University, Professional) of Perpetrators by Type of Violence (Past 12 Months)

|

University relations

|

Work/professionnal relations

| Other lien | Total | Size (perpetrators) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student | Staff | Other | Coworker or manager | Client or other | ||||

| Psychological or social violation | 65.7 | 6.3 | 1.2 | 13.3 | 1.4 | 12.1 | 100 | 1154 |

| Sexual harassment | 34.9 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 10.2 | 2.9 | 45.7 | 100 | 1210 |

| Physical or sexual assault | 38.0 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 4.6 | 1.6 | 51.2 | 100 | 550 |

| Rape or attempted rape | 41.5 | 0.0 | 6.6 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 46.3 | 100 | 106 |

| Source: SAFEDUC (UPCité & Sciences Po, 2024). | ||||||||

| Scope: Students at Sciences Po and Université Paris Cité in initial education or apprenticeship who reported experiencing at least one act of violence in the past 12 months. | ||||||||

| Reading: 65.7 % of reported perpetrators of psychological or social violations were students. | ||||||||

Students represent a significant proportion of perpetrators across all categories of violence, ranging from 65.7% for incidents of psychological or social violation to 34.9% for those involving sexual harassment. At least one perpetrator in three is another student. The proportion of perpetrators from university staff (faculty members, research supervisors, administrative, technical, or maintenance staff) is relatively low for all types of violence studied, although not negligible: they account for less than 10% of perpetrators in each category of violence.

It is not surprising that the proportion of university staff among the cited perpetrators is much lower than that of the student population, given that students interact daily with a greater number of their peers than with university staff. However, while acts of violence are less frequently perpetrated by university staff, the existence of a hierarchical relationship with the victims is likely to amplify the negative consequences and hinder the continuation of studies (for instance, in the case of a doctoral programme).

Professional relationships play an important role in the overall occurrence of violence. Approximately 70% of the student population report engaging in paid work or undertaking an internship during the last 12 months. When narrowing the analysis to this subgroup, the proportion of professional relationships increases slightly, although it still does not surpass the prominence of university-based relationships. Indeed, colleagues or supervisors account for 15.6% of perpetrators of psychological or social violations, 12.3% of perpetrators of sexual harassment, 4.6% of perpetrators of physical or sexual assaults, and 7.2% of perpetrators of rape or attempted rape.

Finally, the proportion of perpetrators from outside the university and work environment is significant for incidents of sexual harassment (45.7%), physical or sexual assaults (51.2%), and rape or attempted rape (46.3%). Within these external relationships, extra-university or extra-professional relationships (friends, intimate relationships, dates, etc.) are distinguished from individuals described as "unknown".

Are "Strangers" Truly Unknown Individuals?

In the SAFEDUC survey, the interpretation of the option "a stranger" should be approached with caution. Due to the structure of the questionnaire (Note 2), it likely allowed respondents to refer to both absolute strangers (for example, individuals encountered in public spaces, etc.) as well as people they may have recognised or met briefly (such as at a university event, a party, etc.). Therefore, the interpretation of the "stranger" category should be considered alongside other contextual information, such as the location where the violence occurred (section 3.1).

Consequently, the tables concerning the nature of the relationship with the perpetrators of violence are restricted to respondents who answered this question, excluding those who identified the perpetrator as a "stranger" (table 10). The percentage of "strangers" identified through the question on the status of the perpetrators is consistently presented in the commentary of the tables to provide context for its interpretation. Lastly, this contextualisation draws on additional information, particularly regarding the location of the violence, to clarify the profile of the "strangers" identified20.

Note 2: The Category "Stranger" in the SAFEDUC Survey

SAFEDUC is distinctive in its approach to distinguishing between the status of perpetrators (their role within the university, workplace, etc.) and the nature of their relationship with respondents (which may be friendly, romantic, etc.). The aim is to differentiate, on the one hand, the power dynamics that may exist between perpetrators and victims, and, on the other hand, the nature of their personal relationships. This distinction, which is a key feature of SAFEDUC, however, comes with a limitation in the categorisation of so-called “strangers.”

Indeed, the SAFEDUC questionnaire first asked respondents about the status of the perpetrators, with a category labelled “stranger.” Those selecting this option were not then asked about the nature of their relationship with the perpetrators. This two-step filtering process resulted in notably high proportions of “strangers” among perpetrators of violence compared to other surveys. Moreover, the detailed responses describing a “stranger” reveal sometimes inconsistent trends, particularly when the violence occurred in the perpetrators’ or respondents' homes.

These inconsistencies suggest that the “stranger” category may have been used to describe individuals who were generally infrequent contacts, and especially those who were not involved in the respondent's educational or work environment (e.g., mere acquaintances, people met briefly at private events, etc.). In other words, the SAFEDUC survey is imperfect in quantifying the involvement of “strangers” in incidents of violence: it fails to provide a nuanced description of the various situations covered by this term (such as a mere acquaintance, a person recently met at an event, a date, or a stranger encountered in a public space, etc.). Consequently, the figures regarding the proportion of “strangers” should be interpreted with caution.

The breakdown of “other relationships” (neither academic nor professional) varies according to the type of violence. As shown in Table 8, 45.7% of perpetrators identified for acts of sexual harassment are neither known within the academic nor professional contexts. This proportion is further broken down into 41.2% “strangers” and 4.5% individuals with “another status” (likely individuals known but not interacted with within the academic context). Similarly, 51.2% of perpetrators identified for acts of physical or sexual assault are neither known within the academic nor professional contexts, with this proportion divided between 45.6% “strangers” and 5.6% “other relationships.”

In the case of rape and attempted rape, the proportion of perpetrators categorised as “strangers” is much lower: 46.3% of the perpetrators identified are neither known within the academic nor professional context, with this proportion divided into 27.4% “strangers” and 18.9% individuals with “another status.”

The “other status” category (neither academic nor professional, nor “stranger”) is more frequently cited in cases of rape or attempted rape compared to other types of violence. These incidents therefore appear, more so than others, to involve individuals “known” outside of academic settings, whereas acts of sexual assault and physical or sexual integrity violations primarily involve “strangers,” possibly encountered in public spaces or transient locations. This interpretation of the survey results is consistent with the location of incidents of violence committed (at least in part) by strangers (see Table 9).

Table 9: Locations of Acts of Violence Occurring in the Last 12 Months Involving at Least One "Stranger" Among the Perpetrators

| On campus | During a university event | Private context | Work environment | Public place | Other | Total | Size (places) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological or social violation | 20.3 | 7.2 | 32.0 | 8.1 | 30.2 | 2.3 | 100 | 222 |

| Sexual harassment | 6.5 | 0.8 | 22.2 | 3.7 | 64.5 | 2.3 | 100 | 645 |

| Physical or sexual assault | 4.2 | 4.6 | 28.4 | 3.6 | 56.2 | 2.9 | 100 | 306 |

| Rape or attempted rape | 0.0 | 0.0 | 75.0 | 2.5 | 12.5 | 10.0 | 100 | 40 |

| Source: SAFEDUC (UPCité & Sciences Po, 2024). | ||||||||

| Scope: Students at Sciences Po and Université Paris Cité in initial education or apprenticeship who reported experiencing at least one act of violence in the past 12 months and who reported a “stanger” among the perpetrator(s). | ||||||||

| Reading: Regarding acts of violence involving a “stranger”, 64.5% of the places where students reported a form of sexual harassment are public places (off campus). | ||||||||

Important differences emerge between categories of violence when analysing the locations of incidents involving “a stranger.” For sexual harassment acts, public spaces are the most frequently cited locations (64.5% of the cited locations). The same applies to physical or sexual assaults (56.2% of the cited locations).

However, incidents of rape and attempted rape involving at least “one stranger” occur less frequently in public spaces and, in the vast majority of cases, within “events or private settings,” which represent 75% of the cited locations (victim’s or perpetrator’s home or car, private parties or weekends, etc.). The detailed responses further reveal that the victim’s or perpetrator’s home or car account for 45.5% of the locations of rape or attempted rape involving “a stranger.”

In general, the “strangers” who perpetrate rape do not appear to be the same as those involved in other forms of violence. The “strangers” responsible for acts of sexual harassment or physical or sexual assaults seem to be predominantly encountered in public spaces. The figures associated with rape or attempted rape tend to suggest that these perpetrators are individuals who are “acquaintances” or who have been recently met in a private setting, outside of academic or professional spheres, for example, during private events or dates. The analysis of the nature of the relationship between respondents and the perpetrators of the reported violence supports this interpretation.

The Nature of the Relationship with the Perpetrators

The main interpersonal relationships involved in acts of violence (excluding the case of "strangers") are presented in Table 10. The nature of the relationships with the perpetrators varies according to the type of violence.

Table 10: Relationship with the Perpetrator at the Time of the Incident by Type of Violence (Incidents in the Past 12 Months, Excluding "Strangers")

| Couple | Ex-partner | Date | Friend | Acquaintance | Other | Total | Size (perpetrators) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological or social violation | 2.3 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 25.8 | 46.6 | 17.5 | 100 | 1018 |

| Sexual harassment | 1.6 | 2.6 | 5.2 | 21.1 | 44.6 | 24.8 | 100 | 610 |

| Physical or sexual assault | 7.5 | 2.2 | 9.3 | 29.5 | 24.2 | 27.2 | 100 | 268 |

| Rape or attempted rape | 15.5 | 7.1 | 35.7 | 13.1 | 19.1 | 9.5 | 100 | 84 |

| Source: SAFEDUC (UPCité & Sciences Po, 2024). | ||||||||

| Scope: Students at Sciences Po and Université Paris Cité in initial education or apprenticeship who reported experiencing at least one act of violence in the past 12 months and who didn’t reported a “stanger” among the perpetrator(s). | ||||||||

| Reading: 7.1 % of reported perpetrators of rapes or attempted rapes were ex-partners (at the time). | ||||||||

Regarding psychological and social violations, the perpetrators are primarily acquaintances (46.6%). Compared to the figures in Table 6 and Table 8, it appears that this type of violence is mostly committed by individuals with whom the victim has minimal interaction in the context of their studies. However, a significant proportion of perpetrators are also friends (25.8%), who, among close relations, are the most likely to be identified as perpetrators of such violence.

For sexual harassment, a similar trend emerges: acquaintances and "other" relationships are the most frequently cited interpersonal relationships, followed by friends, who are the most cited perpetrators among close relations. Taking into account the significant proportion of "strangers" indicated in the question on status (41.2% of perpetrators described), this category of violence is predominantly perpetrated by individuals with whom the victim has limited acquaintance, encountered in public spaces and, to a lesser extent, in the study environment. A comparable trend is observed for physical or sexual assaults, although friends make up a larger proportion of the cited perpetrators (30%, excluding strangers).

Regarding rape and attempted rape, romantic and/or sexual relationships are cited much more frequently than in the other categories of violence. "Date"21 relationships dominate among perpetrators of rape or attempted rape, representing 35.7% of the described relationships with perpetrators (excluding strangers). Romantic relationships and former romantic relationships also represent a significant share of the relationships with perpetrators (15.5% and 7.1% respectively, excluding strangers). These figures, combined with the trends identified regarding the locations and status of the perpetrators, present a profile of perpetrators (primarily men) who are known to the victims, possibly only recently, and potentially involved in a context of "chatting up" and sexual experimentation.

Consequences of Violence on Academic and Personal Life

The final module of the SAFEDUC questionnaire asked all individuals who had reported experiencing violence since the beginning of their higher education or in the past 12 months about the consequences of this victimisation. This table therefore presents all individuals who have reported violence since the beginning of their higher education, categorised by types of violence and categories of consequences. These consequences include 14 outcomes that were proposed in the questionnaire, along with the option to report “No particular consequences,” other consequences, “Don’t know,” or “Prefer not to say.” We also provide a focus on the consequences for the academic path of individuals who reported experiencing violence in the past 12 months in Table 12.

An individual may report having experienced multiple types of violence across different categories, and therefore the figures may include the same individual in various categories of violence. However, each individual is only counted once in each category, whether they have reported one or multiple incidents within that category. Furthermore, respondents who reported violence could indicate multiple types of consequences, which is why the totals exceed 100%.

The vast majority of victims report consequences affecting their social, academic, or personal lives. Individuals who report that the violence they experienced had no consequences represent approximately 30% of victims of psychological or social violation and physical or sexual assaults, with this proportion exceeding 36% for victims of sexual harassment. In contrast, only 11% of individuals who reported rape or attempted rape state that there were no consequences.

Violence involving a physical and sexual dimension (physical or sexual assaults and rape or attempted rape) results in more significant repercussions. Rape and attempted rape also show a higher representation of all types of consequences. For example, while the impact on social life outside of university is 39% for psychological or social violations and 34% for sexual harassment, it reaches 42% for physical or sexual assaults and rises to 60% in the case of rape or attempted rape. It is worth noting, however, that psychological or social violations, which mostly occurs within the institution itself, has a significant effect on the academic sphere, as well as on health.

Regarding social life at university, all types of violence show high and fairly consistent rates, with nearly half of the victims (between 39% and 51%) reporting such consequences. Social life outside of university, as well as romantic and sexual life, are even more significantly impacted in cases of physical violence: for example, 60% of victims of rape or attempted rape report an impact on their social life outside campus, and 71% report an impact on their romantic or sexual life, compared to more moderate rates for other types of violence. Furthermore, the health of victims appears to be particularly compromised, with an observed impact on 38% to 49% of victims in categories 1, 2, and 3, which exceeds 72% for cases of rape or attempted rape.

Table 11: Consequences of Victimisation Since the Start of Higher Education on Academic and Personal Trajectories

| Commitment in studies | Social life at university | Social life outside university | Sex life or love life | Health (mental of physical) | No particular consequence | Size (victims)1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological or social violation | 32.9 | 49.0 | 38.5 | 26.9 | 43.6 | 28.2 | 1886 |

| Sexual harassment | 25.3 | 38.6 | 34.1 | 26.2 | 37.8 | 36.3 | 2338 |

| Physical or sexual assault | 31.0 | 44.2 | 41.9 | 37.1 | 49.2 | 29.8 | 1318 |

| Rape or attempted rape | 45.6 | 51.1 | 60.2 | 70.9 | 72.4 | 11.0 | 399 |

| Source: SAFEDUC (UPCité & Sciences Po, 2024). | |||||||

| Scope: Students at Sciences Po and Université Paris Cité in initial education or apprenticeship who reported experiencing at least one act of violence since entering higher education. | |||||||

| Reading: 32.9% of students who reported experiencing a form of psychological or social violation say that the violence they experienced (including violence from the other categories) impacted their commitment in their studies. | |||||||

| 1 A single individual may report several categories of violence. As a consequence, an individual can be included in the sample size of several categories. However, an individual is only counted once in each category, whether they reported one or more incidents belonging to that category. Individuals reporting violence could select several types of consequences. | |||||||

Regardless of the type of violence experienced, victims report that it has had repercussions on various aspects of their lives. Psychological or social violations, which predominantly occurs within the institution, affects the victims' engagement in their studies and their social life within the university. Physical or sexual assulats, along with rape or attempted rape, negatively impact the victims' romantic or sexual life and their health (Table 11).

Data from the subsample of violence recorded during the past 12 months (Table 12) confirm a notable deterioration in the academic trajectories. Individuals reporting having experienced rape or attempted rape in the last 12 months are more likely than others to state that this has had consequences, regardless of the nature of these consequences. Several aspects of academic life are affected by having experienced violence: absenteeism, motivation to continue studies, changes in academic direction or location, as well as interactions with fellow students and university staff. For example, approximately 11% of individuals reporting having been victims of sexual harassment claim that it had an effect on their absenteeism, compared to around 23% of those reporting having experienced rape or attempted rape. These figures demonstrate that, regardless of the nature of the violence, victims suffer consequences that alter their engagement, integration within the institution, and, more broadly, their academic trajectory.

Although less frequently mentioned, changes in academic direction or location reflect a significant break in the university trajectory. Around 14% of individuals reporting having been victims of rape or attempted rape are considering or have made such a change. A decline in motivation to continue their studies is frequently cited (by nearly 38% of individuals reporting having been victims of rape or attempted rape). This decrease in motivation, combined with difficulties in social interactions and increased absenteeism, constitutes a challenge to equality of opportunity.

Table 12: Consequences of Victimisation in the Past 12 Months on Academic Trajectories

| Absenteeism | Motivation | Academic career or place of study | Exam outcomes | Your relations with other students | Your relations with staff at your institution | Size (victims)1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological or social violation | 15.6 | 30.7 | 8.4 | 13.8 | 39.4 | 8.7 | 1000 |

| Sexual harassment | 11.2 | 20.4 | 5.0 | 9.3 | 23.3 | 4.5 | 1392 |

| Physical or sexual assault | 15.5 | 24.8 | 6.0 | 12.6 | 29.3 | 4.9 | 634 |

| Rape or attempted rape | 23.2 | 37.6 | 13.6 | 23.2 | 40.8 | 5.6 | 125 |

| Source: SAFEDUC (UPCité & Sciences Po, 2024). | |||||||

| Scope: Students at Sciences Po and Université Paris Cité in initial education or apprenticeship who reported experiencing at least one act of violence in the past 12 months. | |||||||

| Reading: 15.6 % of students who reported experiencing at least one act of violence in the past 12 months say that the violence they experienced (including violence from the other categories) impacted their absenteeism. | |||||||

| 1 A single individual may report several categories of violence. As a consequence, an individual can be included in the sample size of several categories. However, an individual is only counted once in each category, whether they reported one or more incidents belonging to that category. Individuals reporting violence could select several types of consequences. | |||||||

Conclusion

The SAFEDUC survey contributes to a better understanding of the extent of gender-based and sexual violence (GBSV) within the student population of two major higher education institutions, as well as the context in which these incidents occur. The methodological choices and the experience gained from SAFEDUC aim to facilitate the replication of such a survey in other higher education and research institutions. This is a significant challenge: to better understand the scale of the phenomenon in order to design effective institutional policies to combat these types of violence.

Bozon, Michel. 1995. “Les rapports entre femmes et hommes à la lumière des grandes enquêtes quantitatives.” In, 655–68. La Découverte. https://doi.org/10.3917/dec.ephes.1995.01.0655.

Bozon, Michel. 2012. “Autonomie sexuelle des jeunes et panique morale des adultes: Le garçon sans frein et la fille responsable.” Agora débats/jeunesses N° 60 (1): 121–34. https://doi.org/10.3917/agora.060.0121.

Brown, Elizabeth, Alice Debauche, Christelle Hamel, and Magali Mazuy, eds. 2020. Violences et rapports de genre: enquête sur les violences de genre en France. Grandes enquêtes. Paris: INED éditions.

Cardi, Coline, Delphine Naudier, and Geneviève Pruvost. 2005. “Les rapports sociaux de sexe à l’université : au cœur d’une triple dénégation.” L’Homme et la Société 158 (4): 49–73. https://doi.org/10.3917/lhs.158.0049.

Coutolleau, Victor, Clara Le Gallic-Ach, and Hélène Hélène Périvier. 2025. “Mesurer Les Violences Sexistes Et Sexuelles En Milieu Étudiant Défis Méthodologiques Et Incertitudes Juridiques.”

Coutolleau, Victor, Clara Le Gallic-Ach, and Hélène Hélène Périvier. 2025. “Synthèse de La Passation de l’enquête SAFEDUC. Représentativité d’une Enquête Sur Les VSS En Milieu Étudiant.”

Jaspard, Maryse, and l’équipe Enveff. 2001. “Nommer Et Compter Les Violences Envers Les Femmes : Une Première Enquête Nationale En France.” Population Et Sociétés, no. 364: 4.

Lebugle, Amandine, Justine Dupuis, and l’équipe de l’enquête Virage. 2018. “Les Violences Subies Dans Le Cadre Des Études Universitaires : Principaux Résultats Des Enquêtes Violences Et Rapports de Genre (Virage) Réalisée Auprès d’étudiants de 4 Universités Françaises.” Paris. https://www.ined.fr/fichier/s_rubrique/28685/document_travail_2018_245_violences.de.genre_universite.fr.pdf.

Mellins, Claude A., Kate Walsh, Aaron L. Sarvet, Melanie Wall, Louisa Gilbert, John S. Santelli, Martie Thompson, et al. 2017. “Sexual Assault Incidents Among College Undergraduates: Prevalence and Factors Associated with Risk.” Edited by Hafiz T. A. Khan. PLOS ONE 12 (11): e0186471. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186471.

- Interdisciplinary Institute for Gender Studies and Research, funded by IDEX UPCité (https://citedugenre.fr/)

- The weighting was constructed based on the following margins obtained from the administrative data of the two institutions: gender category (dichotomised into "women" and "men" due to the absence of other administrative categories relating to gender identity), year of study, scholarship status, and the socio-professional category of one of the parents.

- The convention defines violence against women as "any act of gender-based violence [gender-based violence] that causes or is likely to cause physical, sexual, psychological, or economic harm or suffering to women, including the threat of such acts, coercion, or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, both in public and private life."

- The section dedicated to exposure to acts of violence was introduced with the following text: "The following questions concern events you may have experienced since the beginning of your higher education studies and within a student context. These may include incidents that occurred within your institution, but also outside of it, for example, during an internship, work placement, or in your student social life (friendship, romantic relationships, etc.). If you have changed course or institution more than once, the first questions cover all these periods as long as they pertain to your higher education studies."

- Minor adjustments were made to update the description of certain events (evolution of the legal definition of rape, better consideration of online violence, etc.). The preprint of an article summarising the methodological and legal difficulties of the survey includes these modifications (Coutolleau, Le Gallic-Ach, and Hélène Périvier (n.d.a), available online, particularly pages 23-26).

- As indicated in Note 1, the question asked to approach the incidents of rape or attempted rape does not fully correspond to the definition of rape in the French context. Indeed, Article 222-23 of the French Penal Code defines rape as "any act of sexual penetration, of any kind, or any act of oral-genital contact committed on the person of another or on the person of the perpetrator by violence, coercion, threat, or surprise" (Légifrance, consulted online on 19/03/2025). The notions of "violence, coercion, threat, or surprise" were not retained for the question, in favour of a formulation that more directly referred to the victim’s consent ("without your consent"). This substitution, which brings the wording of the question closer to the definition of rape set by the Istanbul Convention (Article 36) than to the French legal definition, was primarily made for accessibility reasons: the terms "violence", "coercion", "threat", and "surprise" may be ambiguous or difficult to apply to one's personal situation (what is meant by "violence", "coercion", etc.). Using a logic based on the respondents' consent appeared to be more appropriate in this respect, given that they were the best placed to define the boundaries.

- Indeed, the calculation of weighted rates requires knowledge of the proportion of non-binary individuals or those preferring another term within the student populations of the two institutions. This information was not recorded in the administrative data.

- The gap between women and men since the beginning of studies, although small, is significant at the 5% threshold (Chi-squared test, applied to raw and weighted data). The gap over the last 12 months, however, is not significant at the same threshold (for both raw and weighted data).

- A significant gap at a threshold below 1% (Chi-squared test, applied to raw and weighted data) was found both for the last 12 months and since the beginning of higher education.

- The gender gap regarding incidents of physical or sexual assault is significant at a threshold below 1% for both measured time frames (Chi-squared test, applied to raw and weighted data).

- The gender gap regarding incidents of rape or attempted rape is significant both since the beginning of higher education (threshold below 1%) and in the last 12 months (threshold of 1%, Chi-squared tests applied to raw data).

- Non-binary individuals are significantly more likely to report experiencing acts of violence than both men and women combined since the beginning of higher education, particularly psychological or social assaults (0.1% threshold, Chi-squared test), personal assaults of a sexual nature (1% threshold, Chi-squared test), and assaults on physical or sexual integrity (5% threshold, Chi-squared test). If other differences are not significant at the 5% threshold, this result may stem from the small sample size of respondents in this category.

- According to Chi-squared tests comparing victimisation between women and non-binary individuals or those identifying by another term, the only significant difference (at a threshold below 1%) appears for the prevalence of psychological or social assaults since the beginning of higher education. For all other types of violence and time frames, differences between the two groups are either not significant or the sample sizes are insufficient to conclude.

- The time frame since the beginning of higher education is not a reliable time frame for making direct comparisons between institutions for several reasons. First, this time frame may include periods spent at different institutions (e.g., preparatory courses, other universities, or prestigious schools). Secondly, victimisation since the start of higher education increases with the length of studies. Thus, this time frame involves different effects related to the duration and trajectory of studies, which are partially limited by using the time frame of the last 12 months.

- The survey at Nantes University reports a rate of rape or attempted rape of around 2% for its entire student population. The question used to approach these incidents was slightly different from that of SAFEDUC, as it included the notions of "violence, threat, coercion, or surprise" (the full report "Living Environment During Studies and Exposure to Sexual and Gender-Based Violence" (2023), Nantes University, available online [Consulted on 19/03/2025]).

- The raw rate for this type of violence is 11.8% at Sciences Po, 10.1% at UPCité, and 10% at Nantes Université, with identical wording of the question in both surveys.

- These gaps between heterosexual men and non-heterosexual individuals are significant at the 1% threshold for psychological or social assaults in the last 12 months, or 0.1% for other incidents (Chi-squared test applied to raw data. Due to the small sample size of heterosexual men reporting incidents of rape or attempted rape, a Fisher’s Exact test was used).

- These gaps between heterosexual women and non-heterosexual women are significant at the 0.1% threshold (Chi-squared test applied to raw data).

- The questionnaire specified that "by 'essential', we mean 'necessary to meet the necessities of daily life (housing, food, access to healthcare...), including the possibility of having a social life'."

- Despite this contextualisation, the measurement of the involvement of unknown individuals in SAFEDUC remains imperfect and calls for further exploration in future surveys. These would benefit from maintaining the distinction between status and the nature of the relationship but by reversing the order of the questions when administering the survey: first asking about the nature of the relationship with the perpetrator ("friends", "romantic relationships"), including one or more "Unknowns"; then asking respondents about the status of the perpetrator (e.g., student). It would also be pertinent not to apply a filter between the two questions, particularly because students who are otherwise "unknown" may be responsible for acts of violence.

- These relationships were approached in the questionnaire using the option "A 'Date' relationship (you dated but did not consider yourselves engaged).

SAFEDUC is a quantitative research project led by the Sciences Po Gender Studies Programme, which is being implemented as part of the partnership between Université Paris Cité and Sciences Po, and is based on an endowment granted under the Paris University Excellence Initiative 2019 (IdEx UP19).

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to thank everyone who contributed to this research. Thanks to Nawale Lamrini and Sarah Pauloin, Data Protection Officers, as well as the legal and communications departments of the partner institutions, who supported the project. The development of the questionnaire and the preparation for its administration benefited from the valuable advice of a Monitoring Committee. The deployment of the questionnaire was carried out with the support of the team at Sciences Po's Center for Socio-Political Data (CDSP), and the research protocol benefited from the recommendations of the Inserm Ethics Review Committee. Thank you to the participants of the OFCE internal seminar for their valuable comments. We would also like to thank the Sciences Po student groups and associations who actively participated in the survey deployment. The discussions prior to the administration provided valuable field feedback, and their involvement in communicating about the survey greatly contributed to the dissemination of the questionnaire. Students also played a key role in promoting the survey among their peers at the various targeted sites. Finally, the research team warmly thanks colleagues from Nantes Université and those from the Observatory of Sexist and Sexual Violence in Higher Education (FR) for sharing their experience and the results of their own survey.

Contact

For enquiries related to this research/report, please contact presage@sciencespo.fr.

Press Contact: media@sciencespo.fr.