From November 2013 to the end of January 2014, my life was to a large determined by the arrival and departure times of Air France flights into the main international airport of Douala in Cameroon. Airports have rhythms and for three months I danced according to the tunes of the work shifts of the Cameroonian police, the constraints of private security staff, and the routines of the French policeman on patrol at the airport.

This very focused fieldwork endeavour contributes to the research programme “Global Mobility and the Governance of Migration” at the CERI and forms part of a 4 ½ year long research project on the governance of migration and development and the global distribution of social risks and care needs. Launched in November 2011, this project was created as part of a larger research programme at the VU Amsterdam on “migration law as family matter”.[1] Together with an advisory board of renowned researchers, five researchers collaborate for four years to unsettle and reveal the implications of transnational family life for the governance of migration by states. Other fieldwork sites of this research project covered welfare hotels in Paris, social protection mechanisms of Cameroonian care workers abroad, the implementation of the bilateral agreement between France and Cameroon, as well as interviews with participants of France’s ‘voluntary’ return programme.

When I set out to work on control mechanisms at the airport in Douala, it was important for me to win the trust and collaboration of both the Cameroonian and the French police active at the airport. I directly approached the two French police officers without further mediation – stressing that I had been given access to do research at the French consulate office before. While neither of them fully understood why I want to accompany them on their nightly routine walks through the airport, they gave me permission and explained the purpose of their presence and work to me. With respect to the Cameroonian police, I was wary of the protective and secretive potential of a highly hierarchical police organization. A Cameroonian support organization for deportees, for example, had only ever been able to work due to informal connections with individual police officers. Official requests for access to their airport had never succeeded.

I thus chose a more indirect route to gain access to the Cameroonian police. A Cameroonian research colleague had personal connections with key figures at the airport. By presenting ourselves as collaborators, our research endeavor gained in legitimacy because it was backed by the prestige of a local institution. The intention to collaborate on the implementation of migration policy in Cameroon was genuine, but eventually proved unfeasible. By the time the research followed up on inadmissibles not only at the airport, but also in prison and in court, my collaborator judged the topic too close to human rights and too dangerous for his/her professional future. Once the introduction to the airport commissioner had been made, trust had been established and welcoming me (including with a personal farewell gift at the end) had become an act of excelling in an exercise of transparency and efficiency. Again the exact meaning of what research implies was not entirely shared. On our first encounter, I was promised statistics and the rest of my period of ethnographic observations consisted in stimulating conversation while different officers typed up numbers from their registers. Their statistical ambitions were high enough for me to have sufficient time to sit and observe their working routine.

I had initially been afraid that trust with one police authority would diminish my potential for access to the other police authority. I was thus relieved when following the routines of the French police officer did not lead me into the office of the Cameroonian commissioner. In the end, I realized that animosities between both police forces are much lower than I had anticipated, but also that they are not obliged to collaborate on boarding denials. On a day to day level, carrier sanctions mean that decisions to not board a Cameroonian traveler are formally taken by the airline companies and de facto carried out by private security companies, such as SICAS. Much of the day to day burden of preventing “illegal migration” has thus shifted to private companies and the French police looks to the Cameroonian police much more for targeted interventions on specific cases of fraud.

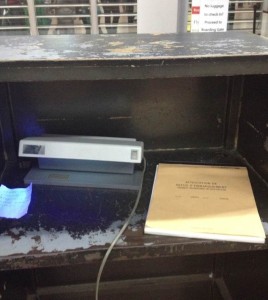

In order to gain insights into the working of the main security company involved with border controls at Cameroonian airports, I also contacted management staff for interviews in their office and carried out more informal conversations with street-level border employees. I observed controls of travel documents and interactions with aspiring travelers. In comparison to my research with the French and Cameroonian police, SICAS staff on all levels much more readily grasped the importance and manner in which I was studying border controls at an airport. They openly addressed the logistical and operational difficulties they were facing in their work. In their narratives, the French police officer figured more prominently than the Cameroonian police.

Migration control arguably occurs ever more through exit than through entry controls. It seems thus all the more important for researchers and migrant support organisations to follow this trend and devote attention to control mechanisms in countries of departure.

[1] http://www.rechten.vu.nl/en/research/top-research/migration-law-as-a-family-matter/index.asp