Sustainable Buildings

20 October 2022

Sustainable Batteries

28 October 2022By Chloe Costa, Malena Ullrich and Maria Callewier

From phones to washing machines, no product is safe from the European Commission’s mission of lowering the environmental impact of products and moving towards a more circular economy. For the better part of two decades the EU has been trying to transform the market and guiding consumers and producers alike towards more energy efficient products through eco-design and energy labeling. But where did this regulation come from and does it tick enough boxes to warrant a more extensive update?

Eco-design in the EU

Eco-design is the integration of “environmental aspects into the product development process, by balancing ecological and economic requirements” (definition by the European Environmental Agency[1]). The crucial idea of eco-design is to consider the entire product life-cycle, from raw materials, to production, shipping, and disposal with the aim of reducing adverse environmental impacts across all life-cycle stages.

However, there are many different approaches to incorporating eco-design requirements into policy. The EU has adopted the logic of eco-design in the 2009 eco-design directive, which establishes a framework for the setting of eco-design requirements for energy related products. The 2009 directive is a revision of the 2005 directive[2], with the central difference being that the 2009 directive applies to all energy-related products rather than just energy-consuming products. Through this revision, the life-cycle perspective is applied more stringently. [3]

The 2009 eco-design directive puts minimum energy performance standards (MEPS) in place. In effect, the Eco-design directive removes the least energy efficient products, which do not meet the minimum standards, from the market.

Energy Labeling in the EU

From shopping for a new refrigerator to buying a new toaster, energy labels are the guiding light for consumers concerned with the energy efficiency of their household products. This energy label goes hand in hand with the aforementioned eco-design directive.

The Energy Labeling regulation has the same scope as the eco-design directive, but instead of minimum standards for removing inefficient products, it encourages demand for the most energy efficient products through energy labels. [4]

Figure 1: EU Energy Label for Commercial Fridges (from 2021)[5]

Market Transformation Theory

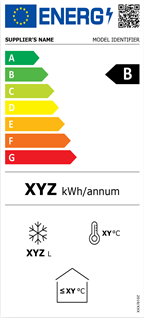

Both eco-design and energy labeling aim to transform the EU market for energy-related products. The theoretical effects, that the policy mix aims at, can be explained using market transformation theory[6]: The MEPS under the eco-design directive act as a market push-factor, by cutting out least efficient products. The energy labels then act as a market pull-factor, by increasing the demand for most-efficient products.

Figure 2: Market Transformation with MEPS and Energy Labels

But did it succeed?

Although theoretically the directive sounds like a sure-fire way to drive out the least-efficient products from the market and improve the general energy efficiency of the concerned products, the reality of the matter revealed quite a few shortcomings.

Firstly, there is a lack of focus on non-energy aspects such as raw material consumption and recyclability, which goes against the original life-cycle perspective that eco-design is based on. Secondly, many inconsistencies with other EU legislation (e.g. Construct Products Regulations) were discovered that either prescribed different assessment criteria for the same products or established separate rules all together. This led to confusion for manufacturers on the criteria and rules they were required to follow. Thirdly, the burden for industries to conform to these standards is quite high, and this is especially true when it comes to the administrative cost for small and medium-sized enterprises who often have less capacity to incorporate new regulation in a rapid manner. Fourthly, the development and implementation process of the policies takes longer than initially anticipated. Taking into account the grace period that is given industries to adapt their products, it often takes almost a decade before a product becomes subject to the regulation. Furthermore, this lengthy process has as a side-effect that recommendations on industry standards are often outdated by the time they go into effect. Stakeholders also requested to be brought in earlier during the development process and for the European Commission to be transparent on what basis policy choices are made. Lastly, a significant portion of potential energy savings are lost due to a high level of non-compliance (10-20%). Nevertheless, this non-compliance does not always stem from unwillingness of the companies to comply. For manufacturers to comply, they need to get the conformity of their product evaluated. However, there are many different interpretations of the assessment of the harmonized standards and some member states don’t possess the necessary qualified laboratories to conduct these tests. This makes it either impossible or very costly for manufacturers to adhere to the standards set out in the eco-design directive.[7]

That is not to say that the directive was not successful at all. Evaluations showed a move towards more energy efficiency in all products, as well as positive feedback from stakeholders on the directive’s role in driving out the least-efficient products from the market. Moreover, it was estimated that by 2020, eco-design and energy labeling delivered enough energy savings per year to cover Italy’s energy consumption in 2010.[8]

Still, more can be done…

On the 30th of March 2022, the European Commission issued a proposal for a regulation establishing eco-design requirements for all products in the EU internal market. This seems like the natural progression of the current Eco-design directive by extending its scope from only energy-related products to all physical goods on the EU market, with a particular focus on resource-intensive industries such as textile, plastics, construction, and electronics.

The objective of the new Eco-design for Sustainable Products Regulation is to make all EU products more durable, reusable, reparable, upgradable, recyclable, and generally less harmful to the environment.

To do so, the legislation will set out performance and information requirements specific to each product group. Each product will also be required to have a Digital Product Passport informing consumers on these requirements. Another crucial element of note included in this regulation is the banning of the destruction of unsold goods. Indeed, the Commission is planning to ban the destruction of unsold goods for particular groups of products that have the most negative environmental impacts. For other products, companies will be required to publicly disclose and publish the number of unsold goods thrown away and why they were discarded. However, these rules will be less stringent for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises.

All of these policies are in line with the EU’s circular economy package and the new circular economy action plan which are key pillars of the European Green Deal.

Why is a move towards a circular economy important?

According to the World Economic Forum, a circular economy is “an industrial system that is restorative or regenerative by intention and design.”[9] This means that products are designed with their whole-life cycle and associated environmental impacts in mind.

Figure 3: Circular Economy Model[10]

As figure 3 depicts, in a circular economy, in part thanks to eco-design and recycling technologies, products are designed to be able to be recycled and reused. This will reduce the need to create brand new products, and thus reduce the need to extract additional raw materials.

Hence, developing a circular economy will immensely reduce waste generation and associated GHG emissions, and alleviate the stress on natural resources. Moreover, the circular economy model also brings about positive social and economic benefits. Indeed, having a circular economy promotes the reuse of local resources, which decreases dependence on imported raw materials, improving resource security and independence. Additionally, a move towards a circular economy incentivizes the development of new, more innovative, and more competitive industrial models, stimulating economic growth and job creation. In fact, an EU report estimates that adopting circular economies in Europe would create 700 000 jobs in the EU alone by 2030.

Therefore, given that 80% of a product’s environmental impact is determined at the design phase, the new Eco-design for Sustainable Products regulation is crucial to move towards a circular economy – bringing the EU one step forward to a net zero emissions economy by 2050.

Yet, how have stakeholders reacted to this proposal?

Groups representing various EU industrial sectors, such as BusinessEurope, Applia, Euratex, and Orgalim, recognize the great potential of the new eco-design regulation, yet raise a number of concerns. These groups worry about the legal uncertainty, overlap in legislation, and over-regulation that this new policy might cause. These industrial stakeholders are also concerned with the significant investment, especially in R&D, that would be needed to comply with the new eco-design requirements. Overall, although they welcome the new proposal, stakeholders stress the importance of involving the various industrial sectors to develop cost-efficient and proportional requirements with “proven environmental benefits that exceed the costs to industry.”[11]

On another note, environmental NGOs, including the Environmental Coalition on Standards, criticize the gaps in the proposal, such as the fact that it does not directly address the issue of packaging.

Conclusion

Eco-design and energy labeling has clearly shown its effectiveness, however many shortcomings were identified by both stakeholders and the European Commission themselves. In an attempt to strive for more ambitious climate policies and resolve some of the issues noted in the original Eco-design directive, a new regulation is in the making. During a class discussion, the students of the “European Green Deal” class have made a few things clear: it will be a difficult exercise to weigh and include the different stakeholders’ interest in the exact specifications of this new directive. Additionally, the need for transparency in both developing the policies, as well as how producers are implementing them is at the top of the list for almost all of the attendees, no matter if they were asked to represent consumers or big clothing companies. Yet, only time will tell if this new legislation will be effective.

[1] “Eco-Design.” European Environment Agency, www.eea.europa.eu/help/glossary/eea-glossary/eco-design.

[2] “Directive 2005/32/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 July 2005 establishing a framework for the setting of ecodesign requirements for energy-using products”, Official Journal, 2005, L191, ISSN 1725-2555

[3] “Directive 2009/125/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 establishing a framework for the setting of ecodesign requirements for energy-related products”, Official Journal, 2009, L285, 10.3000/17252555.L_2009.28

[4] “Regulation (EU) 2017/1369 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2017 setting a framework for energy labelling and repealing Directive 2010/30/EU”, Official Journal, 2017, L198

[5] “Press Corner.” European Commission – European Commission, ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/deck09/MEMO_19_1596. Accessed 18 Oct. 2022.

[6] Glemarec, Yannick. “Catalying Climate Finance. A Guidebook on Policy and Financing Options to Support Green, Low-Emission and Climate-Resilient Development” UNDP, 2011.

[7] Bacian, I. “Revision of the Ecodesign Directive”. European Parliamentary Research Service. European Parliament. April 2022

[8] “Impact Assesment: COMMISSION REGULATION (EU) …/… Laying Down Ecodesign Requirements for Refrigerating Appliances Pursuant to Directive 2009/125/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council.” European Commission, SWD(2019) 341 final, European Commission, 1 Oct. 2019, ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/1552-Review-of-ecodesign-requirements-for-household-cold-appliances_nl.

[9] Chatterjee, Deyasini. “What Is a Circular Economy? Is It as Important as Reports Suggest?” Emeritus, 13 Sept. 2022, https://emeritus.org/blog/circular-economy-sustainability/

[10] “Circular Economy: Definition, Importance and Benefits.” News: European Parliament, 26 Apr. 2022, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/economy/20151201STO05603/circular-economy-definition-importance-and-benefits.

[11] Šajn, Nikolina. “Ecodesign for sustainable products.” European Parliamentary Research Service, European Parliament, May 2022.