Sustainable Batteries

28 October 2022

Circular Economy

7 November 2022By Tereza Fabulova, Maria Kipp, Juahna Da Mota

A Complex and Multidimensional Definition:

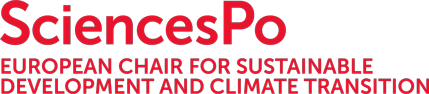

In Europe, more than 30 million individuals are thought to live in energy poverty. The persistent problem of the most disadvantaged households in Europe is the disproportionality of the effects of energy poverty. Although there is no one definition for the phrase “energy poverty,” it often refers to situations in which households spend an excessive amount of money on energy or cannot afford to satisfy their basic energy demands. Early studies on energy poverty in the EU focused heavily on defining the issue; early articles referred to it as “fuel poverty” rather than “energy poverty”.

The definitions of energy poverty that do exist may typically be divided into two types; one that concentrates on the vastly disproportionate proportion of family income spent on energy; and one that concentrates on families that do not spend enough on energy (Rademaekers, et al. 2016). But these broad categories only provide a very condensed understanding of a subject that actually involves many different dynamics, including economic, social, behavioral, policy, geographical, and temporal. As a concrete example, it is usually not taken into consideration that energy poverty exists in the summer as well, influencing the existing data and measurements on energy poverty.

Energy poverty has a variety of root causes, including low earnings, subpar housing, and inefficient equipment. Macroeconomic development, household final energy use, the availability of various energy sources, energy pricing, housing efficiency, and climate are other major contributors to energy poverty. Although the problem is widespread throughout Europe, the rates of energy poverty are higher in nations in Southern and Central-Eastern Europe.

Energy poverty is a multifaceted phenomenon that is difficult to express with a single measure. In order to measure its level, the combination of various indicators have to be used. As a result, it is difficult to measure and monitor energy poverty. It considers the uniqueness of every nation and is based on difficult-to-measure information. However, some nations are able to identify and quantify the energy poverty indicators such as France, Belgium or Austria.

Energy Poverty on the EU-Level

The EU has introduced legislative and non-legislative measures to tackle the issues of energy poverty on a European level. As it is a multidimensional topic and social policy lies at the responsibility of member states the EU has mainly focused on energy policies to tackle the issue.

Energy poverty becomes a policy focus on the EU level

Energy poverty for the first time appeared in EU legislation in 2009 as part of the 3rd Energy package. Since then the problem of energy poverty has been increasing in the EU, the Clean energy for all Europeans package (proposed in 2016 adopted in 2019) made energy poverty a key concept of EU legislation and a policy focus. Moreover, the Clean Energy for All Europeans introduced the NECPS, a 10-year plan on how member states align their climate and energy goals. The NEPC required MS to assess the numbers of households living in energy poverty and outline adequate measures on how to address the issue. Nevertheless, an Assessment of these plans by the EPOV has proven that the majority of EU countries still lacks a concrete definition of energy poverty and fails to present targets and measures to address the problem and resources available for it. Consequently, in spite of the urgency of the topic many of the member states in their strategies outlined in 2020 still lack a targeted strategy to tackle energy poverty.

In 2020 the EU Commission published a “Recommendation on Energy Poverty” aiming at supporting the Member States. It includes guidance on indicators to measure energy poverty, encourages best practice sharing and outlines options to access EU funding.

The European Green Deal and Energy Poverty

The European Green Deal (EGD) – the EU´s strategy to reach zero carbon emissions by 2050, calls for ambitious policies and thereby increasing the risk of energy poverty. To enable a just and fair transition – a declared goal of the EGD – measures to mitigate energy poverty need to be an integral part of the implementation.

Fit for 55 package

The Fit for 55 – package suggests reforms of existing EU legislation and new initiatives that pave the way to reach the goal of reducing GHG by 55% until 2030. Based on the recommendation on energy poverty published by the Commission the “Fit for 55” includes suggestions to identify key drivers of energy poverty as well as measures that address the problem structurally by introducing legislative and non-legislative measures.

Legislative measures tackling energy poverty:

Reform of Energy Efficiency Directive (COM/2021/558 final)

The suggested reform of the Energy Efficiency Directive would introduce higher targets for reducing energy consumption, and energy savings. Furthermore, it suggests a benchmarking system for member states to outline their national contributions to the EU 2030 goal. Regarding energy poverty, it underlines the importance that member states make best possible use of public funding to protect and empower vulnerable consumers and alleviate energy poverty. Member states shall when implementing energy efficiency obligation schemes or other measures financed by a national fund prioritize people affected by energy poverty and vulnerable costume and as stated in the Directive, where applicable social housing.

Non-legislative measures tackling energy poverty:

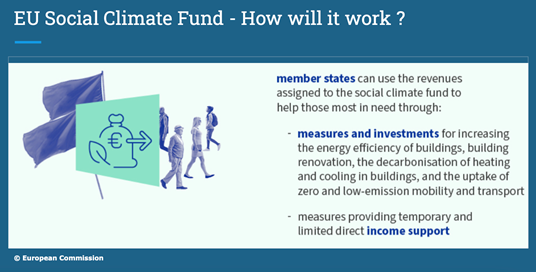

EU – Social Climate Fund

An example for a mitigation measure on EU -level is the introduction of a “Social Climate Fund”, which is part of the Fit for 55 – strategy and aims at counteracting the negative effects of the introduction of the Emission Trading System (ETS) for road transportation and building. The introduction would result in increased prices of fossil fuel and will place a higher burden on low- and middle-income households. To mitigate the negative effects the EMS will be complemented by the Social Climate Fund. The revenues of the allowances will flow into the Fund. The goal of the fund is to support green investment and to finance direct income support for vulnerable households and Member States. In spite of the potential of the instrument to decrease the inequality within and between EU countries, the fund has been criticized for being too small and not able to cover the cost needed to counteract the negative consequences of the new EMS. That clearly demonstrates the need for policies which mitigate energy poverty as an integral part of the policies.

The Diverse Situations and Policies at the National Level

The question of energy poverty is treated differently by the member States leading to a diversity of situations, policies, initiatives and challenges at the national level.

Palliatives or Preventives Measure ?

Some member states have a social definition of energy poverty, they tend then to focus on palliative measures to support vulnerable households.

Sweden : strong social system covering costs for adequate warmth households and “warm rent” where energy costs are a fixed component.

Greece : Social Tariffs by the Greek Power Corporation offer around 30% discount.

When the States define energy poverty as a social but also energy policy concern, they tend to use preventive measures improving the efficiency of the housing.

France: a mixed definition is used. In 2020 the government created a credit tax called “MaPrimeRenov”. Its allocation is based on the income of the household and the planned energy performance improvements.

Vulnerable households

Low-income households are often the most affected by energy poverty, especially because of the high prices of energy and the higher risk of poverty.

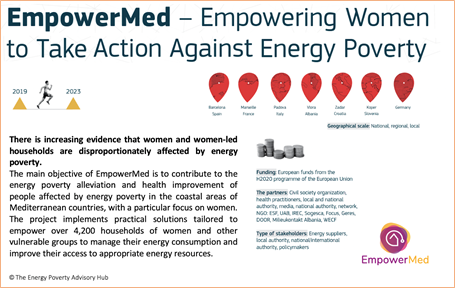

Women are particularly vulnerable since they are already more affected by poverty in general.

Example of initiative: EmpowerMed to reduce energy poverty of the women-led households

Older people, young children, disable people and chronically ill people are almost among the most vulnerable especially in winter and summer time when the houses can be heated or cool sufficiently. Cyprus: a national program aims to reduce energy poverty of disable households with small-scale energy renovations

“Transport poverty” and housing conditions

The energy performance of buildings is a key dimension.

Portugal: Due to a lack of insulation and inadequate heating systems, the buildings are not designed for cold winter. Example of initiative : The NGO Just a Change (JAC) rebuild homes for people in need from 2020.

Transport poverty depends a lot on policies led in each country.

Bulgaria and Hungary present expensive public transport not affordable for low income families while in Spain or Cyprus the prices made public transport a real option for the low-income households.

Nevertheless, the current energy crisis clearly demonstrates the consequences of the lack of clear and dedicated action to tackle energy poverty on national level and underlines the need for increased EU funding and a solidarity mechanism between member states to enable redistribution and to not risk the implementation of the European Green Deal.

Sources:

Defard, C., Bergoënd, A. (2021, September 22). Make the Social Climate Fund a game changer to tackle energy poverty. Jacques Delors Institute. https://institutdelors.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/BP_220922_make-the-Social-Climate-Fund-a-game-changer_Defard_EN.pdf

European Union, European Comission. (2021). Proposal of the European Parliament and of the Council on energy efficiency (recast) (COM(2021) 558 final).https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0558

European Union, European Parliament. (2021). Revising the Energy Efficiency Directive: Fit for 55 package(Briefing). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2021)698045

European Commission, Energy poverty in the EU (Website)https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/markets-and-consumers/energy-consumer-rights/energy-poverty-eu_en

European Union, European Council, Infographic – Fit for 55: a fund to support the most affected citizens and businesses.https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/fit-for-55-social-climate-fund/

Magdalinski, E. Delair, M. Pellerin-Carlin, T. for the Jacques Delors Institute. (2021, February). Europe needs a political strategy to end energy poverty. https://institutdelors.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/PP259_210202_Precarite-energetique_Magdalinski_EN.pdf

Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy, European Parliament. (2015, August) How to end Energy Poverty? Scrutiny of Current EU and Member States Instruments. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/563472/IPOL_STU(2015)563472_EN.pdf

Taylor, K.(24.22.2021) Europe’s social climate fund too small to make a difference, critics say. Euractive.https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/europes-social-climate-fund-is-too-small-to-make-a-difference-critics-say/

The Energy Poverty Advisory Hub, for the European Commission. (2021, November). Tackling energy poverty through local actions Inspiring cases from across Europe. https://energy-poverty.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-11/EPAH_inspiring%20cases%20from%20across%20Europe_report_0.pdf