The Diademe Life Project : toward the smartest city ?

15 November 2022

Report on Climate Action shared with G20 Summit Leaders

16 November 2022By Manon Chenailler, Kristina Feikova, Mara Foerster

Zero Pollution Ambition: Still a Long Way to Go?

By Manon Chenailler, Kristína Feiková and Mara Förster

In April 2022, the European Commission adopted its action plan ‘Towards Zero Pollution for Air, Water, and Soil’, thereby adding another major component to the legislative framework of the European Green Deal. This action plan envisions a world in which pollution has been reduced to levels that are no longer hazardous to human health and outlines the procedures required to get there.

Throughout the following blog post, we consider the EU’s zero pollution ambitions in more detail, by providing an overview of what pollution is in the first place, why we should care about it, what the EU is currently doing to reduce it and finally how close we are to reaching the zero pollution goals.

How Do We Define Pollution?

The EU defines pollution as the ‘direct or indirect introduction […] of substances or heat into the air, water or land which may be harmful to human health or the quality of aquatic ecosystems or terrestrial ecosystems […], which result in damage to material property, or which impair or interfere with amenities and other legitimate uses of the environment’, as outlined in Article 33 of the framework for community action in the field of water policy.

Following this definition, pollution can be categorised in three different ways: firstly, along the types of pollutant (namely chemicals, dust, noise, and radiation), secondly, along the sources of pollution (point-source or nonpoint source-pollution) and thirdly in relation to the medium affected by pollution (namely soil, air and water pollution). The latter categorisation will be used as our framework of analysis as it is the approach primarily utilised within the legislative framework of the EU.

Air Pollution

Air pollution refers to the contamination of air due to the presence of substances in the atmosphere that are harmful to the health of humans and other living beings, to the climate or to materials.

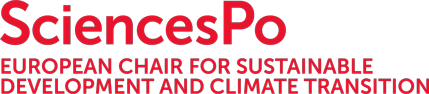

Thanks to the implementation of policy requirements, key air pollutants have declined significantly throughout the past three decades. Still, this has not been enough as for example the reduction of Particulate Matter (PM2.5) has only decreased by 28% since 2000, despite its significant impact on public health.

Water Pollution

Water pollution occurs when toxic substances enter water bodies such as lakes, rivers, or seas by dissolving in them, depositing on their bed, or suspending in the water. This pollution is of concern as it degrades the water quality and thus destroys aquatic ecosystems. Pollutants can also seep through and reach groundwater – an area of grave concern due to the difficulty of clearing it up once polluted. Plastic in particular marks a key water pollutant, accounting for 95% of the waste accumulating on shorelines, sea surface and sea floor.

Soil Pollution

Soil pollution is caused by the presence of human-made chemicals or other substances that negatively alter the natural soil environment. In comparison to air and water pollution, it is more difficult to assess and hardly visible. It is estimated that there are as many as 2.5 million potentially contaminated soils across Europe, with only one-third of those having been already identified. As soil is a non-renewable resource, it takes hundreds of years to generate just one centimetre of topsoil. Henceforth, tackling the impact of soil pollution becomes increasingly significant in the future.

Figure 2: Sources, degradation, and effects of soil pollution, Source: FAO

Why Should We Care About Pollution?

Social and Environmental Costs

Pollution is one of the main drivers of biodiversity loss, directly threatening the survival of more than 1 million of the planet’s 8 million plants and animals. Furthermore, pollution has a significant impact on public health, causing one in eight deaths in the EU every year. Vulnerable groups, such as children or the elderly, are at disproportionately higher risks of pollution-related diseases, making tackling the latter also a question of fairness. Thus, many lives could have been saved if pollution was reduced.

Tragedy of the Commons

Pollution is an example of the tragedy of the commons as the mediums of water, air, and soil mark scarce resources, which are non-excludable and rivalrous in consumption. Thus, each individual has an incentive to use and pollute them at the expense of everyone else and there exist few mechanisms to reduce the incentive for over-using common goods. With every individual acting in their rational self-interest, resources such as air, water and soil become victims of overconsumption and underinvestment. One solution to prevent their depletion due to pollution is through regulation, which is why the EU has put into place an ambitious legislation to tackle pollution.

What Is the EU Doing to Reduce Pollution?

Zero Pollution Hierarchy

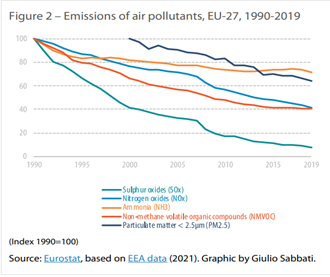

To achieve its goal of zero pollution by 2050, the EU uses a framework of zero pollution hierarchy, which establishes the priorities of the ambition.

The most important pillar of the EU’s environmental policies is prevention at the source (in all stages of the circular economy) based on the precautionary principle. The precautionary principle enables decision-makers to adopt precautionary measures when scientific evidence about an environmental or human health hazard is uncertain and the stakes are high. It first emerged during the 1970s and has since been enshrined in several international treaties on the environment, in the TFEU (Article 192) and the national legislation of certain Member States. The ‘polluter pays’ principle (enshrined in Article 191 TFEU) is the commonly accepted practice that those who produce pollution should bear the costs of managing it to prevent damage to human health or the environment. Both concepts are important in global environmental governance, as not all countries abide by these principles and therefore, they remain a point of contention.

The other two pillars of the zero pollution hierarchy are minimisation and elimination. Where fully preventing pollution from the outset is not (yet) possible, pollution should be minimised. Finally, when pollution occurs, it should be remediated, and the related damage compensated. This hierarchy, which is based on the values of transparency, accountability, participation, and reliability also encourages innovation, as it promotes zero pollution production and recycling in all stages of the process.

Long-Term Goals: 2050 A Healthy Planet for all

The EU Action Plan ‘Towards Zero Pollution for Air, Water and Soil’ sets out an overall vision of the world in 2050 where pollution is reduced to levels that are no longer harmful to human health and natural ecosystems. It ties together all relevant EU policies to tackle and prevent pollution, with a special emphasis on how to use digital solutions to reach this goal. It also emphasises that slowing down all economic activities is not the way the EU envisions its path towards zero pollution, and therefore degrowth is not an option that the EU is promoting right now. Instead, the EU wants to ‘sustain prosperity while transforming production and consumption modes and directing investments towards zero pollution’.

Intermediary Targets: 2030

Much like the EU’s other environmental goals, the Action Plan ‘Towards Zero Pollution for Air, Water and Soil’ plan also includes the following intermediary targets to be achieved by 2030:

- Reduce the number of premature deaths caused by air pollution by 55%

- Reduce waste, plastic litter at sea (by 50%) and microplastics released into the environment (by 30%)

- Reduce nutrient losses and chemical pesticides’ use by 50%

- Reducing by 25% the EU ecosystems where air pollution threatens biodiversity

- Reducing the share of people chronically disturbed by transport noise by 30%

- Significantly reducing waste generation and by 50% residual municipal waste

The EU considers the 2021-2027 multiannual financial framework and NextGenerationEU to be budgetary opportunities to support its zero pollution ambition.

How Close Are We to Reaching Zero Pollution?

Overall, we still have a long way to go before reaching the EU’s zero pollution ambition for 2050. Looking more closely at the three mediums affected by pollution, one can further observe a greatly varying protection, depending on how extensively EU legislation has been established. Further challenges are additionally posed due to the so far limited success in enforcing the ‘polluter pays’ principle and in light of the present global energy crisis.

Air Pollution

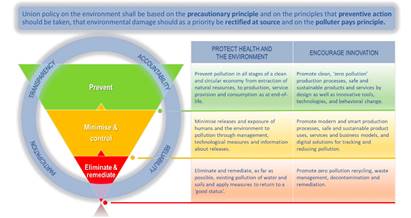

As already established, a significant reduction of major pollutants can be observed since the 1990s. Nonetheless, major challenges remain on the road to zero emissions as air pollution does not have a clearly defined ‘safe level of exposure’. Due to this lack of ‘safe exposure levels’, countries and international organisations set different standards, thereby creating an inconsistency that becomes particularly apparent when comparing EU standards to those of the WHO:

As highlighted in the graphic, WHO air pollution standards are significantly stricter than EU standards. Taking the example of the fine particle PM2.5, whilst following EU standards 4% of the EU’s urban population has been exposed to pollution, while according to WHO standards it was 96% of the population. Based on this stark contrast, the EEA estimates that 178.000 lives could have been saved if the EU adopted standards resembling those of the WHO.

The greatest limitation to reducing air pollution is, nonetheless, the lack of policy consistency and enforcement within the respective member states. Ensuring compliance is very tedious and energy intensive. This is further highlighted by the vast amount of infringement cases still occurring. For example, when the second Clean Energy Outlook was published in December 2020, a total of 31 infringement cases were still reported in 18 member states.

Water Pollution

Regarding its water and marine legislation, the EU is too slow to keep up with science by updating its list of priority substances deemed harmful for EU water. More concretely, the EU faces the main challenge that existing legislation currently does not sufficiently address the contaminants of major concern, such as microplastics and pharmaceuticals. Furthermore, its risk evaluation of substances does not currently consider the combination effects of mixtures on health. Also, wastewater treatment plants are (despite being used as the primary cleaning mechanism for water pollution) quite limited in their ability to remove contaminants, succeeding to only remove 90% of the microplastics. As such there is still a great need to ensure better enforcement mechanisms and make existing regulation more responsive to scientific findings.

Soil Pollution

The medium of soil pollution lags most behind between the three regarding the zero pollution goals. Although the ambition exists to create a comprehensive soil framework by 2023, soil pollution is currently only partially regulated due to overlap with other regulated mediums of pollution and individual soil pollution legislations of member states.

‘Polluter Pays’ Principle (PPP)

Despite the centrality of this principle to the EU’s zero pollution ambitions, it still suffers from major implementation weaknesses.

Firstly, the application of this principle to individual member states and sectors of industry is vastly uneven. This can be led back to unclear concepts and definitions indicated within EU legislation. PPP further rests upon the assumption that the polluter will always be able to pay. The principle, however, has not been fully developed for cases when this isn’t the case e.g., insolvency.

Secondly, even if the extent of pollution for each emitter can be successfully determined and the polluter is capable of paying the costs, the full costs of pollution are currently not yet charged. For air pollution, the medium of pollution with the most accurate data, only 44% of the incurred damages have successfully been charged. Meanwhile, water and soil polluters were charged almost nothing.

Therefore, whilst considering that pollution still occurs even if the polluter is not successfully charged for its costs, somebody eventually will have to come up for the damages which amount to €750 billion p.a. across the EU. Currently, it is indeed often the EU budget which is sometimes utilised for those clean-up actions. However, this cannot be considered a sustainable solution in the long term, with the implementation gap cost for the present failure of successfully implementing EU environmental legislations being estimated to amount to €55 billion p.a.

Outlook on the Present Energy Crisis

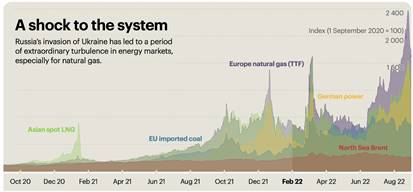

A further challenge to the EU’s zero pollution ambition is posed by the present global energy crisis, thereby re-emphasising the underlying question on the trade-off between the pollution ambition and energy security.

With the necessity of finding sufficient heating sources for the entire population to get through the coming winter, concerns are raised that vital legislation may be pushed back towards an unknown future (e.g., REACH). In addition, countries are resorting back to heating sources (e.g., old wood stoves or using freshly cut wood) which emit high degrees of harmful pollutants into the air. Therefore, it is possible that this winter marks a step backwards regarding our long term-goal of reaching the EU zero pollution ambitions, entailing a re-prioritisation of energy-security needs over environmental and health concerns.

Conclusion

From this one can conclude that although the EU is on a good track towards identifying key polluters and establishing legal frameworks to limit their emission into the environment, we can still observe great challenges in their successful implementation. Nonetheless, we argue that although these initial pushbacks may occur, the EU will be able to take it as an opportunity to improve its legislative framework in the long-term to achieve its ambitious zero pollution ambitions by 2050.

Bibliography

Agence européenne pour l’environnement. ‘Signaux de L’AEE 2020 – Vers une pollution zéro en Europe’. Publication, 2020. https://www.eea.europa.eu/fr/publications/signaux-de-l2019aee-2020-vers.

Brink, Patrick ten, Alberto Vela, and Patrick ten Brink and Alberto Vela. ‘Green Deal: The Light at the End of the Crisis Tunnel’. Social Europe (blog), 12 October 2022. https://socialeurope.eu/green-deal-the-light-at-the-end-of-the-crisis-tunnel.

Brun, Marie-Amélie. ‘EC Makes Steps to Tackle Water Pollution but Falls Short on Chemical Mixtures’, 26 October 2022. https://eeb.org/european-commission-makes-steps-to-tackle-water-pollution-but-falls-short-on-chemical-mixtures/.

Directorate-General for Environment. ‘Zero Pollution Monitoring and Outlook Workshop’. European Commission, 25 May 2022. https://environment.ec.europa.eu/news/zero-pollution-monitoring-and-outlook-workshop-2022-05-25_en.

European Commission. ‘Commission Warns Germany, France, Spain, Italy and the United Kingdom of Continued Air Pollution Breaches’. Text. European Commission, 15 February 2017.

European Commission. ‘European Green Deal: Commission Proposes Rules for Cleaner Air and Water’. Text. 26 October 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_6278.

European Court of Auditors. Air Pollution: Our Health Still Insufficiently Protected. Special Report. (European Court of Auditors. Online). LU: Publications Office, 2018. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2865/80097.

European Environment Agency. ‘Europe’s Air Quality Status 2022 — European Environment Agency’. Briefing, 1 April 2022. https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/status-of-air-quality-in-Europe-2022/europes-air-quality-status-2022.

European Parliament. ‘The EU’s Zero Pollution Ambition: Moving towards a Non-Toxic Environment’, 3 May 2022.

European Parliament and Council. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy, Pub. L. No. 32000L0060, Article 33 (2022). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/60/oj.

European Parliamentary Research Service. ‘Revision of the EU Ambient Air Quality Directives’, October 2022. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2022/734679/EPRS_BRI(2022)734679_EN.pdf.

International Energy Agency. ‘World Energy Outlook 2022’, 27 October 2022, 524. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/c282400e-00b0-4edf-9a8e-6f2ca6536ec8/WorldEnergyOutlook2022.pdf

National Geographic Society. ‘Point Source and Nonpoint Sources of Pollution’. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/point-source-and-nonpoint-sources-pollution, 20 May 2022. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/point-source-and-nonpoint-sources-pollution.

World Health Organization. ‘Air Pollution’. Accessed 19 October 2022. https://www.who.int/health-topics/air-pollution.

World Health Organisation. ‘Microplastics in Drinking-Water’, 2019. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/wash-documents/microplastics-in-dw-information-sheet190822.pdf?sfvrsn=1b4d77ac_3.

Zimmermann, Antonia. ‘Energy Crisis Sparks Air Pollution Fears’. POLITICO, 19 September 2022. https://www.politico.eu/article/russia-coal-shortage-causes-energy-crisis-poland-hungary/.