French Climate Action

5 December 2022

Governance and monitoring

7 December 2022By: Sebastian Baciu, Cecile Legris, Allegra Semenzato

Introduction

The European Green Deal (EGD), the European Union (EU)’s main pathway towards decarbonisation, is expected to bring major transformations to the Union’s socio-economic system. But the EGD will also bring a significant external impact on non-EU countries. As the EU is a great economic power, one of the most obvious implications of the EGD is on global markets and trade. This is why it is important to look at how the EU’s foreign policy will adapt to the goals of the EGD, the EU stance in the international climate arena, and what options the EU has at its disposal in order to reach its decarbonisation targets, including the often overlooked adaptation policies.

Economic and financial instruments for implementing the EU Green Deal

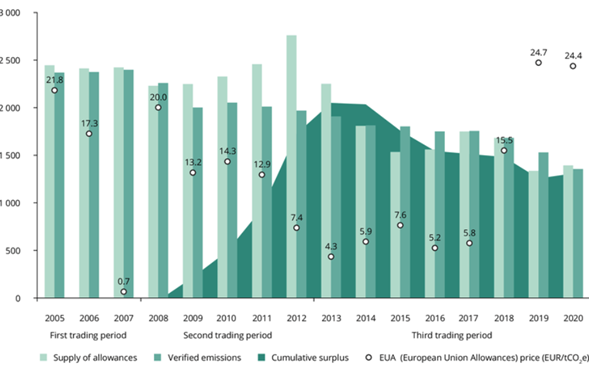

Conventionally, the EU relies strongly on market-based instruments in order to design and implement its climate and environmental policies. In this way, the Union is able to create the framework within which the economy itself can gradually move towards net-zero technologies without explicit intervention from the Union. The ETS and the CBAM are two examples of the EU’s market-based tools designed to deliver on the EGD, alongside the Green Taxonomy.

The revision of the ETS

Launched in 2005, the EU Emissions Trading System aims to create a price signal for carbon by putting an annual cap on emissions from power plants, industrial factories and the aviation sector. Within that cap, EU companies are required to buy emission allowances corresponding to their CO2 emissions. This is intended to encourage companies to move away from fossil fuels and adopt net-zero technologies as the costs of emission allowances become higher. Thus, the ETS is a type of environmental regulation that follows the polluter pays principle and that stays within the mandate of the Commission.

Figure 1. Million tonnes of CO2 equivalent (Mt CO2e)

However, the effectiveness of ETS has been undermined by one major loophole: the provision of free allowances for sectors that are considered to be at risk of “carbon leakage”. The rationale behind the free allocation of emission permits is to respond to the concerns of certain industries that claim they are disadvantaged by the EU’s stringent emission standards. Thus, certain sectors are allowed to pollute for free in order to support their competitiveness. For this reason, selling extra allowances is not a good strategy for the climate because this influences the price signals needed to encourage companies to transition to net-zero technologies (Figure 1).

In order to achieve the target of cutting GHG emissions by 55% by 2030, the Commission proposed in July 2022 a review of the EU ETS Directive as part of the Fit for 55 package. The new ETS sets to further reduce the total cap on emissions (which will subsequently increase the price of emission allowances) and to phase out free allowances granted under the current EU ETS. Moreover, the proposal also aims to introduce a new emissions trading system for buildings and transport. However, critics have pointed out that this extension of the ETS would compromise the just transition since it would put all consumers on the same level, regardless of their revenues. The Commission’s proposal for a review of the ETS is currently in the process of trilogue negotiations at the EU level.

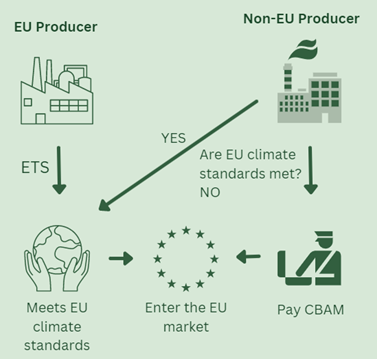

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)

As part of the Fit for 55 package, the Commission has also included a CBAM that would be targeted at imports from third countries. This is meant to complement the ETS by discouraging offshoring and carbon leakage. The CBAM would gradually replace the system of free allowances that currently exists under the EU ETS. The Commission itself has pointed out that free allocations are no longer an effective tool as they come with a big financial and climate cost, despite being effective in fighting carbon leakage. Instead, starting from 2026, EU importers will be required to purchase emission certificates equal to the weekly price of EU ETS allowances. This would ensure an equivalent price on carbon for imported products and for EU products, and thus a level playing field between domestic EU producers (which are already subject to the EU ETS) and third-country exporters, which will become subject to the CBAM when importing goods (Figure 2).

This would apply to the industries with the highest risk of carbon leakage: cement, iron and steel, aluminium, fertilisers and electricity. The CBAM would cover imports from all third countries, except those participating in the ETS. What this means in practice is that third-country manufacturers of products covered by the CBAM would have to pay an extra fee for their exports. The CBAM could also encourage partner countries to embrace carbon pricing which would reinforce the so-called Brussels effect. On the other hand, this may also create a so-called “resource reshuffling” whereby third-country producers would export low-carbon products to the EU while keeping dirtier versions for domestic and non-EU markets.

Figure 2. The CBAM procedure

From January 2023 to December 2025, over the course of the transition period, importers would only be responsible for calculating and reporting carbon emissions in line with EU requirements. And then from January 2026 onwards, importers will have to purchase emission certificates for the amount of CO2 emitted.

The first session of trilogue negotiations on the CBAM took place in July 2022. Many NGOs have pointed out that while the CBAM can be useful for reaching the EU’s climate goals, it can have a negative effect on third countries, especially those located in Africa and south-eastern Europe. Critics also point out that a carbon border adjustment can increase economic competitiveness but does not reduce global emissions substantially.

The EU Green Taxonomy

The green taxonomy is another important element in the EU’s toolbox for the energy transition. It aims to classify which economic activities can be marketed as sustainable investments according to multiple environmental criteria. Rules for most sectors came into effect this year, covering investments including steel plants, electric cars and building renovations. However, the proposal has also come with controversies since the Commission proposed in February this year the inclusion of gas and nuclear power plants in the taxonomy. It is important to mention here that the taxonomy does not ban investments in activities not labelled “green”, but it limits the projects that companies and investors can claim are climate-friendly. This should – at least in theory – limit the expansion of greenwashing.

EU Climate Adaptation

Why adaptation policies?

Figure 3. The MOSE flap gates

Source: MOSE Venezia. Retrieved from https://www.mosevenezia.eu/mose/

Do you know what the image represents? It is showing the MOSE, a system of flap gates that was finalised two years ago and will protect Venice from the more frequent high tides. Recently, since the season of high tides has begun, the city has been experiencing a series of extremely high tides and without these dams in place, the city would have flooded causing huge damage to Venetians and the whole economy of the island, as it happened in November 2019. The MOSE is an excellent example of climate adaptation against flooding. After years of debates on the topic and slow-downs in its construction, with predictions of continuous sea-level rise and more ferocious storms, rains, and winds, the system is proving to be a wise investment for Venice to build resilience and protect its residents and tourism industry from damages and losses caused by frequent flooding.

Within climate governance, attention is often paid to mitigation strategies, namely those addressing aiming at decreasing GHG emissions while those favouring the adjustment of territories and local communities to climate change remain out of the spotlight. Nevertheless, we are already touched by the impacts of climate change today even in Europe: the heat waves that hit the continent last summer, the floods that happened in Germany, the wildfires in Greece, and the coastal degradation and rising sea levels affecting the Mediterranean countries, to mention a few examples. This is why both the Stern Review and the most recent IPCC report highlight the importance of adaptation to reduce vulnerability, cope with the impacts of climate change, and increase resilience. Specifically, there are three takeaways from the IPCC report that are worth mentioning: 1. climate change is not a future threat and its impacts are more severe than expected (just in Europe, economic losses caused by climate-related extreme events already average over EUR 12 billion per year); 2. adaptation is crucial; and 3. the risks will escalate quickly with higher temperatures prompting irreversible impacts of climate change.

But where does the EU stand on adaptation policies?

Adaptation has been part of the European climate framework since the 2010s, first with a series of white and green papers bringing the issue to the policymakers’ agenda, and then with the publication of the EU Strategy on adaptation to climate change in 2013. The latter called for states to prepare a climate adaptation plan. However, the 2013 Strategy was recently updated to align it with other climate strategies like the farm-to-fork strategy, and more in general with the EU Green Deal. The 2021 Strategy sets 4 objectives, namely to make adaptation smarter, by focusing on better gathering and sharing data on climate risk and losses, faster, and more systemic, given the impacts of climate change on everyone in our societies. Then it also aims at stepping up international action on adaptation through international mechanisms like the Global Goal on Adaptation which was agreed upon at COP21. Moreover, the online platform Climate-ADAPT was enhanced to favour the dissemination of knowledge on adaptation. The 2021 Strategy also mentions three priorities. Firstly, integrating adaptation in macro-fiscal policies by, for instance, pushing for the adoption of insurance against climate-related risks. Then, boosting nature-based solutions and local governance.

Nature-based solutions (NBSs)

Nature-based solutions (NBSs) represent an umbrella concept referring to “solutions that are inspired and supported by nature, which are cost-effective, simultaneously provide environmental, social and economic benefits and help build resilience”. These have multiple benefits, stemming from increasing nature diversification in urban landscapes, to improving biodiversity, health and well-being. It is for these great advantages that the European Commission believes in the importance of scaling up these measures to promote adaptation in line with the European Green Deal. An example of an EU-funded project that is focused on NBSs is Connecting Nature. This initiative aimed at positioning Europe as the global leader in the innovation and implementation of NBSs by bringing together different stakeholders from industries to communities and non-governmental organisations. Among other things, it allowed cities with expertise in NBSs like Glasgow and Bologna to exchange best practices and knowledge with follower cities.

Figure 4. Connecting Nature

Local governance

Then, local governance plays a great role in adaptation strategies because adaptation policies are context-specific. There is a European initiative focused on local action worth mentioning: the Covenant of Mayors. It was first introduced in 2008 and then strengthened in 2014 with the inclusion of the “Mayors Adapt” facility, and it aims at providing assistance to scale up climate action to those municipalities that voluntarily decide to join. In fact, the only requirement to become a member of the Covenant is to pledge action to support the implementation of the EU GHG-reduction targets. It is widely considered to have succeeded in boosting local climate action by promoting bottom-up governance, favouring cooperation among different levels of government, and driving the adoption of contextual climate policies.

International climate action: the role of the EU

We must work relentlessly to adapt to our climate – making nature our first ally. This is why our Union will push for an ambitious global deal for nature at […] COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh”. These are the words of the President of the European Commission on November 6, the opening day of the 27th UN Climate Change Conference (COP27). For two weeks, the parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) met to discuss and negotiate actions to tackle climate change.

In 2015, in line with the goal of stabilising greenhouse gas concentrations “at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system” defined by the Convention in 1993, the EU and its member States ratified the Paris Agreement. Seven years later, the EU still plays a key role in international climate negotiations and has deeper climatic engagements. The European Green Deal is for instance one of the European keys to achieving the goal of climate neutrality by 2050 and States have submitted nationally determined contributions at the end of 2019 to give their pathways to reach this ambition.

These national ambitions have been increased during COP27. The Vice President of the European Commission, Frans Timmermans has announced the modification of nationally determined contributions to reach a 57% decrease in EU’s CO² emissions in place of 55%. The President of the European Commission has indeed called for an increased effort at the global level to reach the Paris Agreement goals during the Conference.

“The EU will stay the course […], because it is essential to keep the ambition of the Paris Agreement within our reach”

Ursula Von der Leyen, President of the European Commission – 2022 State of the Union

Raw materials: a new source of dependency?

By achieving climate neutrality, the EU has to be careful to not create new dependencies and has to tackle the existing ones. The green transition requires scarce raw materials that the EU has to import from other countries.

The President of the European Commission has already warned the Member States on the subject during her State of the Union last September: “Without secure and sustainable access to the necessary raw materials, our ambition to become the first climate-neutral continent is at risk.”

Solar panels are a good example of the stake of the EUs’ independence of raw materials. The decarbonization of energy is one of the major tools to tackle climate change and the development of renewable energies through solar panels especially is one of the objectives of the RePowerEU Plan presented by the European Commission last May. However, 75% of the world’s production of silicon, the main component of the panel, is Chinese. More generally, China has a virtual monopoly on rare earth and permanent magnets. So there is a massive dependency on the EU for the development of its solar panels which can have an impact on the achievement of climate neutrality.

Also, as we have seen with the Ukraine War and the European dependency on Russian gas, natural resources can indeed be used as foreign policy tools.

What responses to this increasing vulnerability?

This growing vulnerability will need to be addressed in two ways: by recycling more of these resources, and by developing alliances with exporting countries. In line with these two solutions, Ursula Von der Leyen made a proposal for a Critical Raw Materials Act in her state of the European Union last September. This act aims to develop a more resilient supply chain by going notably through the development of a European network of raw materials agencies and of strategic storage to prevent supply chain disruptions. In order to frame the ambitions, the EU will finance projects and some targets to reach could be introduced in the EU legislation. Commissioner Thierry Breton has proposed that “at least 30% of the EU’s demand for refined lithium” should come from the EU by 2030. Lithium is notably used for car batteries which are part of the European tools to reach climate neutrality.

Figure 5. Global distribution of rare earth elements

The way forward

After all the targets set and the announcements made it will now be up to member states, local actors, and businesses, to mention a few, to follow with concrete action. There seems to be room for optimism: for the Institute for European Environmental Policy’s 2022 Green Deal Barometer, while 73% of respondents think that the war in Ukraine will impact negatively the Green Deal implementation in 2023, the majority still think that the EU institutions will support the Green Deal to a great extent after the 2024 EU elections.

P.S. If you would like to learn more about the MOSE system and the discussion surrounding it, check this out and this article by the Guardian

Bibliography

Abnett, K., Jessop, S. (2022). “Explainer: What is the EU’s sustainable finance taxonomy?.”

Reuters. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/what-is-eus-sustainable-finance-taxonomy-2022-02-03/

Caserini, S. (2017). Climate policies and strategies in the European Union. In Colucci, A.,

Magoni. M., & Menoni, S. (Eds.), Peri-urban areas in food-energy-water nexus (pp. 3-9). Springer, Cham.

Casert, C. & Bas-Defossez, F. (2022). 2022 Green Deal Barometer. Retrieved from

Claeys, G., Tagliapietra, S., Zachmann, G. How to make the European Green Deal Work

(Policy Contribution Issue n. 13). Bruegel. Retrieved from: https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/wp_attachments/PC-13_2019-151119.pdf

Covenant of Mayors — English. (n.d.). Climate-Adapt.eea.europa.eu. Retrieved from

Delsol, C. (2022). “The European Parliament, the Council and the European Commission

enter the second trilogue negotiations for the adoption of the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).” Blog Droit Européen. Retrieved from https://blogdroiteuropeen.com/2022/10/25/the-european-parliament-the-council-and-the-european-commission-enter-the-second-trilogue-negotiations-for-the-adoption-of-the-eu-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism-cbam-charlotte-delsol/

European Parliament (2022). Review of the EU ETS ‘Fit for 55’ package (Briefing, EU

Legislation in Progress). Retrieved from

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2022/698890/EPRS_BRI(2022)698890_EN.pdf

European Union, European Commission, (2007). Adapting to climate change in Europe-

options for EU action, (Green Paper, (2007) 354 final). Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu

European Union, European Commission, (2009). Adapting to climate change: Towards a

European framework for action (White Paper, (147) final). Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu

European Union, European Commission, (2013). An EU Strategy on adaptation to climate

change, (Communication, (2013) 216 final). Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu

European Union, European Commission, (2018). Report on the implementation of the EU

Strategy on adaptation to climate change, (Communication, (2018) 738 final). Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu

European Union, European Commission, (2021). Forging a climate-resilient Europe – the

new EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change, (Communication, (2021) 81 final). Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu

European Union, European Commission, (2022). Critical Raw Materials Act: securing the

new gas & oil at the heart of our economy – Blog of Commissioner Thierry Breton. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_22_5523

European Union, European Commission. National energy and climate plans . Retrieved from

https://energy.ec

European Union, European Council, (2022). Council sets out EU position for UN climate

summit in Sharm El-Sheikh (COP27). Retrieved from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/10/24/council-sets-out-eu-position-for-un-climate-summit-in-sharm-el-sheikh-cop27/

European Union External Action, (2021), The Geopolitics of Climate Change (with Frans

Timmermans). Retrieved from https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/geopolitics-climate-change-frans-timmermans_en

Institute for European Environmental Policy. (2022). 2022 Green Deal Barometer. Retrieved

from https://ieep.eu/publications/green-deal-barometer-second-edition

Keskitalo, E. C. H., Westerhoff, L. & Juhola, S. (2012). Agenda-setting on the environment:

The development of climate change adaptation as an issue in European states. Environmental Policy and Governance, 22, 381-394.

Levin, K., Boehm, S., & Carter, R. (2022, February 27). 6 Big Findings from the IPCC 2022

Report on Climate Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Retrieved from https://www.wri.org/insights/ipcc-report-2022-climate-impacts-adaptation-vulnerability?utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter&utm_campaign=ipcc

Oztig, L. I. (2017). Europe’s climate change policies: The Paris Agreement and beyond,

Energy Sources, Part B: Economics, Planning, and Policy, 12(10), 917-924.

Pietrapertosa, F., Khokhlov, V., Salvia, M. & Cosmi, C. (2018). Climate change adaption

policies and plans: A survey in 11 South East European countries, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 81, 3041-3050.

Stern, N. (2007). Summary of conclusions. In The Economics of Climate Change (pp. 15-19).

West Nyack: Cambridge University Press.

UNFCCC, Sharm el-Sheikh Climate Change Conference. Retrieved from

Usman, Z., Abimbola, O., Ituen., I. (2021). What does the European Green Deal Mean for

Africa? (Paper). Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from: https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/10/18/what-does-european-green-deal-mean-for-africa-pub-85570