Selected aspects of EU climate action: Adaptation, trade & finance

5 December 2022

EU work programme: What’s on for sustainable development and climate transition?

7 December 2022By Wai Kwan Tang and Emma Eiermann

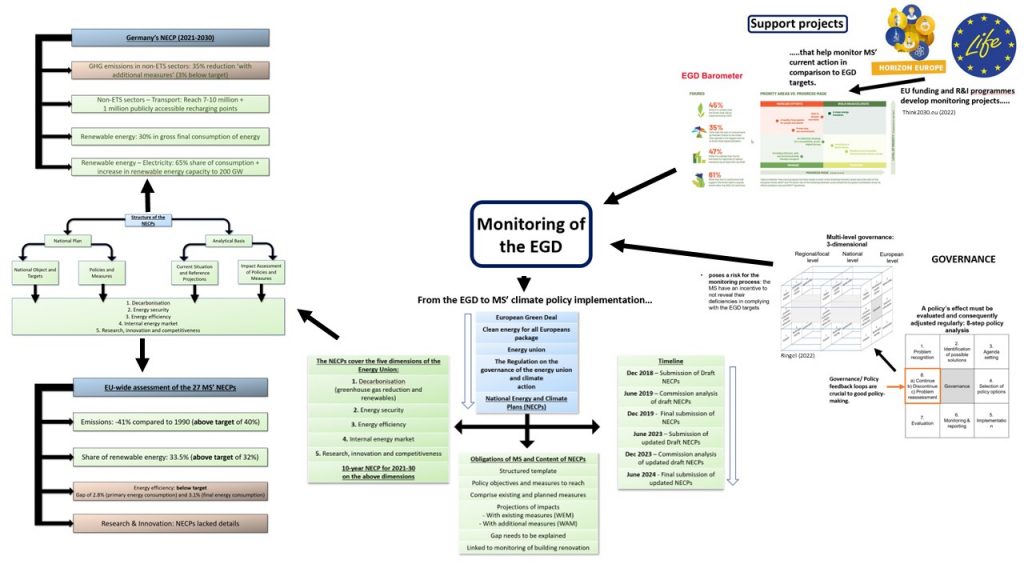

In order to ensure compliance of EU member states (in the following: MS) with the ambitious goals brought forward with the European Green Deal (in the following: EGD), the most crucial part of the EGD – its actual implementation, the translation of the broad EGD targets into detailed policy at the MS level, must be monitored extensively. This may be tedious, but monitoring is in fact very important work.

These monitoring processes are usually subsumed under specific governance structures. In the case of the European Green Deal (and specifically its forthcoming 55% emissions reduction by 2030 target), these are largely subsumed under the “Regulation on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action”, under which the MS have to establish a so-called “National Energy and Climate Plan” (in the following: NECP). The Regulation provides a legal framework for the NECPs, regulating not only the content of the NECP but as well as its format. Moreover, it also establishes the MS’ submission deadlines, thus delineating a clear road map for the MS to follow.

The NECPs serve one main goal: ensuring that the MS comply with the EGD targets by making the MS’ climate action policies comparable, accessible, transparent and visible and thus easily susceptible to public pressure. Putting MS’ policies out into the open adds peer pressure among MS and public pressure on each MS and is thus a crucial, effective soft-power instrument.

The second important monitoring mechanism on the EU level is the MS’ National Long-term Strategies, which must describe the MS’ strategy towards achieving net zero emissions by 2050 at the latest.

Well-functioning governance feedback mechanisms are another crucial element in ensuring effective policy-making overall. A policy’s effect must be evaluated and consequently adjusted regularly, for which the 8-step policy-cycle model of Jann & Wegrich (2007) presents a good template.

Multi-level governance revolves around a three-dimensional axis: the EU level, the national level, and the regional/local level. Multi-level governance also poses a risk for the monitoring process, as it is difficult for, e.g., the Commission, to obtain full information for proper monitoring as the MS have an incentive to not reveal their deficiencies in complying with the EGD targets.

For instance, Germany submitted its NECP draft 6 months after the deadline, delaying the overall policy process. Beyond that, the EU Commission’s assessment of Germany’s draft NECP described its climate action policies as insufficient.

Furthermore, EU-funded programmes such as the R&I Horizon Europe and the LIFE program can also support the monitoring process. For example, those programmes can provide monitoring and benchmarking information on the current state of play of achieving the EGD goals and thus help with monitoring.

The following mind map illustrated the aforementioned aspects visually: