Event: The European Green Deal

17 April 2024

Event Summary: The European Green Deal – An Event in Two Parts

7 May 2024Reflections on the role of start-ups in the digital and green transition, inspired by the OECD workshop ‘Start-ups and scale-ups for the twin transition: Challenges and policy responses’

By Miren Isasi, CEO of GarbiGlobe

Climate change and the way in which industrial practices affect the environment is now extensively proven by a wealth of available data. However, it is not as though the consequences of our practices were previously unknown. In fact, key actors in the oil industry accurately modelled the potential consequences of their activities as early as the 1960s. However, these “inconvenient truths” were ignored by the industry; not wanting to be the bearer of bad news while also thinking they had more time to address their impacts before it was too late. Stanford Research Institute scientists Elmer Robinson and R.C. Robbins presented a report to the American Petroleum Institute in 1968 on the sources, abundance, and fate of gaseous pollutants in the atmosphere, warning the release of carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels could carry an array of harmful consequences for the planet. Similarly, Exxon was aware of climate change as early as 1977—11 years before it became a public issue and yet has spent millions of dollars to promote misinformation and block progress on climate action.

Governments were similarly informed on the potential risks of climate change decades ago, with numerous studies assessing these risks having since been carried out. The National Petroleum Council, an oil and natural gas advisory committee to the Secretary of Energy in the United States, knew about climate change as far back as the 1970s. A 1982 report prepared by the energy division of Oak Ridge National Laboratory, which is funded and contracted by the US Department of Energy, highlights the fact that the US federal government was indeed made aware of the research results.

Nevertheless, several generations of business leaders and politicians chose to leave future generations with the responsibility of addressing the issue. Decades of inaction and a complacent “laissez-faire” attitude, propagated by well-funded institutes, businesses, and governments have inevitably contributed to further deepening the environmental crisis.

Hope is now rightfully, although somewhat reluctantly, being placed in small and agile start-ups to look for solutions to this man-made crisis.

Start-ups offer fertile ground for clever ideas, generated by “out-of-the-box thinkers”, who are unafraid of questioning established norms. This contrasts with traditional corporate leaders who are often constrained by the short-termism of investment bankers focused on maximising shareholder value over stakeholder wellbeing.

Developments in new technologies are facilitating a digital and green transition. This progress is paving the way for increasingly innovative tools that can reduce both pollution and the costs of production, accelerating the implementation and dispersion of these technologies. One such example can be found in the pace of decentralised power production and storage. Owing to a wide variety of renewable energy technologies, individuals and communities now can become energy independent by going off-the-grid in an environmentally friendly manner, without the need for heavy upfront infrastructure investment. Incremental innovations—batteries vs hydrogen for transportation, sodium vs lithium-based batteries, etc.—naturally follow the creative start-up trend, which needs to be supported both financially and with appropriate regulation.

It needs to be noted, however, that most new ideas have been focused on alleviating the symptoms rather than tackling the cause of environmental challenges. To truly understand these underlying issues, we must reflect on the factors that have led us to our current predicament.

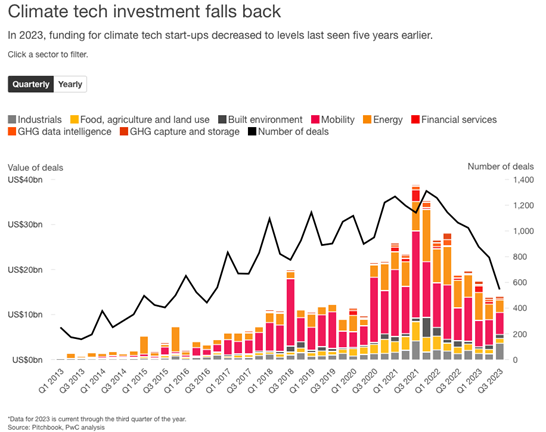

The concept of financial return on investment (ROI) has a significant influence on our actions across various dimensions: social, political, financial, and environmental. In prioritising financial gains, or ROI, there is a risk of underestimating the risk profile of an investment and neglecting the consideration of non-financial risks or future financial liabilities. This emphasis on ROI also extends to how start-ups are measured, which may partially explain the decline in investment in climate technology start-ups.

Beyond a focus on ROI, it is imperative to consider the environmental impacts associated with our pursuit of innovation. The extraction of raw materials used in clean energy technologies often comes with its own environmental costs. In Chile, for instance, the diversion of vast quantities of fresh water—a vital resource in this arid region—for lithium mining operations adversely impacts the brine of the salt flats and in turn, local ecosystems and communities.

We must not repeat the errors of our predecessors by failing to account for the true cost of our actions. In our efforts towards a green transition, it is crucial to support start-ups that address both the causes and symptoms of environmental issues, as they can play a key role in shaping societies that are more environmentally respectful and prosperous.

However, the embedding of ESG principles into executive decision-making is often challenged if it impacts financial returns. The former CEO of Danone, Emmanuel Faber, for example, was first applauded for his ambitious and sustainable growth agenda for the company, only to be forced out when prices of shares began to lag behind competitors. This instance, along with many others, creates a dilemma for executive leaders who are expected to balance their fiduciary obligation to increase company value with the pressing need to address environmental concerns.

Investment funds, pension funds, private equity funds, and banks predominantly favour initiatives that deliver the highest financial returns. Similarly, government tenders continue to focus primarily on financial cost rather than environmental impact. As a result, capital is largely invested in projects unencumbered by ESG principles.

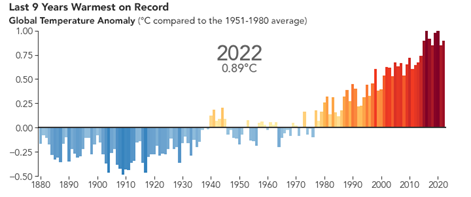

To solve this dichotomy, carbon markets were established under the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, following the “polluter pays” principle. This marked the first agreement among governments to implement a carbon trading mechanism that penalises polluting countries by requiring them to compensate countries that pollute less for their rights to pollute. This pioneer carbon market, which was binding, has since been followed by various voluntary carbon markets around the world that allow companies, organisations, and individuals to voluntarily offset their emissions through the purchase of carbon credits. However, the implementation of carbon markets has often been too limited in scope and compromised by potential conflicts of interest, which have contributed to the continued rise in CO2 emissions and increasing atmospheric temperatures year on year.

Source: ‘World of Change: Global Temperatures’.

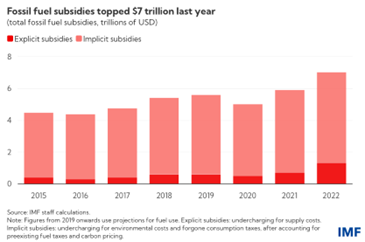

Governments frequently rely on traditional tools like subsidies and taxation to help advance the green transition. However, this approach may risk unintended consequences, such as sector-specific downturns or abrupt market shifts. Moreover, relying solely on fiscal policies often neglects innovative strategies that could better support start-ups and offer new and effective solutions. It is therefore essential for governments to explore and embrace more creative approaches and thereby increase the range of tools at our disposal, which can facilitate a smoother transition towards environmental sustainability.

Governments often face a conflict of interest when their fiscal policies prioritise financial returns over ESG values, jeopardising the success of the green transition. For example, the annual revenues generated by the oil and gas industry, which have averaged close to USD 3.5 trillion since 2018, illustrate this issue. Such significant earnings may help explain the continued incentivisation of fossil fuel subsidies. An example of such a policy is the Tax Reform Act of 1986 in the United States, where oil and gas ventures remain one of the few tax-advantaged investments available to taxpayers. These benefits include 100% tax deductions for both intangible drilling costs (in the first year) and tangible drilling costs, as well as a 15% depletion allowance on gross production revenue, effectively reducing the tax burden on these companies and encouraging continued investment in the sector.

One of the most critical challenges of addressing climate change is that it requires a global response. Yet implementation is complex in a world where national perceived threats often prompt governments to revert to a mercantilist approach, effectively impeding international cooperation. Climate action therefore needs to involve more stakeholders than just governments.

Start-ups that employ innovative, lateral thinking are instrumental in accelerating the green transition. Companies that aim to solve the causes as well as the consequences of past and present pollution are vital players in progressing towards sustainable solutions and should therefore be considered key stakeholders in the climate change dialogue.

Start-ups that utilise free market mechanisms to promote environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles offer executives the opportunity to champion sustainable practices. Implementing pricing metrics that reflect the real costs of environmental damage and remediation could be a strong incentive for companies to invest in R&D, leading to more efficient operations and accelerating carbon emission reductions. Using tools that are already available but applying them in new ways can help transform our current detrimental cycle of carbon and pollution into a virtuous one, ultimately aligning shareholder value with stakeholder interests.

The good news is that significant investment has already been directed to initiatives in the private sector seeking solutions to environmental issues. Over the past decade, for example, climate-focused start-ups received over USD 490 billion through more than 32,000 deals involving upwards of 8,000 start-up companies. Nevertheless, the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero Roadmap estimates that to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, annual investments in clean energy need to reach USD 4.5 trillion by 2030.

Thus, while significant strides have been made, the vast scale of necessary funding highlights that a lot more progress is urgently required.

Bibliography

Banerjee, Neela, John H. Cushman Jr, David Hasemyer, and Lisa Song. Exxon: The Road Not Taken. Brooklyn, New York: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015.

Bonneuil, Christophe, Pierre-Louis Choquet, and Benjamin Franta. ‘Early Warnings and Emerging Accountability: Total’s Responses to Global Warming, 1971–2021’. Global Environmental Change 71 (1 November 2021): 102386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102386.

‘Crown Exploration | Tax Advantages’. https://www.crownexploration.com/tax-advantages.

Goldenberg, Suzanne, and US environment correspondent. ‘Exxon Knew of Climate Change in 1981, Email Says – but It Funded Deniers for 27 More Years’. The Guardian, 8 July 2015, sec. Environment. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/jul/08/exxon-climate-change-1981-climate-denier-funding.

Grantham Research Institute on climate change and the environment. ‘What Is the Polluter Pays Principle?’ https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/explainers/what-is-the-polluter-pays-principle/.

Guest. ‘US Government Knew Climate Risks in 1970s, National Petroleum Council Documents Show’. DeSmog (blog), 19 March 2019. https://www.desmog.com/2019/03/19/us-government-knew-climate-risks-1970s-national-petroleum-council/.

IEA. ‘Executive Summary – The Oil and Gas Industry in Net Zero Transitions – Analysis’. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-oil-and-gas-industry-in-net-zero-transitions/executive-summary.

IMF. ‘Fossil Fuel Subsidies Surged to Record $7 Trillion’, 24 August 2023. https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/08/24/fossil-fuel-subsidies-surged-to-record-7-trillion.

Intelligence, GlobalData Thematic. ‘The Cost of Green Energy: Lithium Mining’s Impact on Nature and People’. Mining Technology (blog), 30 October 2023. https://www.mining-technology.com/analyst-comment/lithium-mining-negative-environmental-impact/.

Milman, Oliver. ‘Oil Industry Knew of “serious” Climate Concerns More than 45 Years Ago’. The Guardian, 13 April 2016, sec. Business. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/apr/13/climate-change-oil-industry-environment-warning-1968.

Perry, A. M., K. J. Araj, W. Fulkerson, D. J. Rose, M. M. Miller, and R. M. Rotty. ‘Energy Supply and Demand Implications of CO2’. Energy 7, no. 12 (1 December 1982): 991–1004. https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-5442(82)90083-4.

PricewaterhouseCoopers. ‘State of Climate Tech 2023: Investment Analysis’. PwC. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/esg/state-of-climate-tech-2023-investment.html.

Rich, Nathaniel. ‘Losing Earth: The Decade We Almost Stopped Climate Change’. The New York Times, 1 August 2018, sec. Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/08/01/magazine/climate-change-losing-earth.html.

Supran, G., S. Rahmstorf, and N. Oreskes. ‘Assessing ExxonMobil’s Global Warming Projections’. Science 379, no. 6628 (13 January 2023): eabk0063. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abk0063.

TIME. ‘A Top CEO Was Ousted After Making His Company More Environmentally Conscious. Now He’s Speaking Out’, 21 November 2021. https://time.com/6121684/emmanuel-faber-danone-interview/.

U.S. Government Publishing Office. Examining the Oil Industry’s Efforts to Suppress the Truth About Climate

Change’. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-116hhrg38304/html/CHRG-116hhrg38304.htm

‘What Is the Kyoto Protocol? | UNFCCC’. https://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol.

World Economic Forum. ‘IEA: Clean Energy Investment Must Reach $4.5 Trillion per Year by 2030 to Limit Warming to 1.5°C’, 28 September 2023. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/09/iea-clean-energy-investment-global-warming/.

‘World of Change: Global Temperatures’. NASA Earth Observatory, 29 January 2020. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/world-of-change/global-temperatures.