New Report Highlights Lagging Sustainable Development in Europe

31 January 2025

Fostering the Future of Green Finance: A Look Back at the Green Finance Challenge with HSBC Continental Europe

10 February 2025By Paula ESPADA BLANCO, Camille FORZY, Sara LEAL DE MATOS-POWELL, Leon PETERS & Ole RINGEN

I. Introduction

Drawing inspiration from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’ during the Great Depression, the past decade has witnessed the emergence of ‘Green Deals’ worldwide as nations strive to address pressing environmental, economic and societal challenges. Many countries have developed strategies to tackle climate change with varying levels of ambition, aiming to ensure economic growth and social progress while transitioning to sustainable practices.

In 2019, the European Union (EU) unveiled the European Green Deal (EGD), a comprehensive strategy aimed at making Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. According to the European Commission, the EGD is more than just climate policy; it is a new growth model that aspires to reshape the EU into a fair, prosperous society with a competitive, resource-efficient economy. Its key objectives include achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions by mid-century, safeguarding environmental health and decoupling economic growth from resource use [1]. The EGD emphasises social fairness and environmental stewardship, making it one of the most ambitious green initiatives to date.

Green Deals in the literature

The EGD has been extensively analysed in academic and policy circles – examining its implications for climate action, economic transformation and social justice. Much of the literature focuses on the transformative potential of the EGD in reshaping European industrial policy [2][3][4], driving the renewable energy transition [5][6], and ensuring social fairness within the green transition [7]. Similar strategies or ‘Green Deals’ around the world have also been analysed in the literature thus far. For example, Lee and Woo evaluate the accomplishments and challenges of the Green New Deal of South Korea as a sustainability transition strategy [8]; Galvin and Healy assess the post-Keynesian economics and tax implications of the Green New Deal in the US [9]; and Masoud Sajjadian puts forward a critique on the UK’s Net Zero Strategy [10].

Despite the wealth of academic contributions on the EGD and similar strategies around the world, fewer academic contributions are offering a comparative analysis between them. Some exceptions include Agora Energiewende’s comparison between the EGD and the Korean Green New Deal [11] and Lenain’s analysis of transatlantic differences between the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the EGD [12]. Besides these unilateral comparisons, there is even less literature available which evaluates these ‘Green Deals’ collectively. The International Energy Agency and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development have published reports comparing international climate strategies, but direct comparisons of ‘Green Deals’ are hard to find. This blog contribution aims to fill that gap by evaluating the EGD alongside other ‘Green Deals’ around the world, assessing their scope and their ambitions, to determine whether the EGD stands unique in its approach. Before delving into the comparison, a terminological clarification is in order.

Defining a Green Deal

The concept of ‘Green Deal’ was first proposed by Michael O’Neill in a policy proposal on green technology and green job creation to overcome economic downturns [13]. A decade later, US journalist Thomas Friedman advocated for a ‘Green New Deal’ in his New York Times column [14]. In 2009, the United Nations (UN) put forward a proposal for a Global Green New Deal, which was inspired by Roosevelt’s New Deal [15]. Like Roosevelt’s New Deal, O’Neill, Friedman and the UN were advocating for the inclusion of pro-environmental actions in economic and social recovery plans following a financial crisis.

It is worth noting that the concept of a Green Deal in policy and academia consistently seeks to reconcile environmental and climate policies with economic recovery, often through Keynesian economic stimuli. In their comparison of 16 Green Deals from the 21st century, Smol defines these as strategies “to create a clean and green economy through implementation of pro-environmental solutions in various sectors, which take into account the three aspirations of sustainable development – the well-being of people, the environment and economic sustainability” [16]. Similarly, environmental organisations like the Sierra Club define it more broadly as “a big bold transformation of the economy to tackle the twin crises of inequality and climate change” [17]. The EGD frames itself as “a package of policy initiatives, which aims to set the EU on the path to a green transition, with the ultimate goal of reaching climate neutrality” [18].

For this analysis, we adopt Shin’s definition as our guiding framework, as it captures the socio-economic and environmental ambitions central to Green Deals. Shin defines a ‘Green (New) Deal’ as “a policy framework accelerating the transition towards decarbonised socio-economic systems through publicly driven economic stimuli programmes that foster job creation and investment in new technologies” [19].

Selected Green Deals

Based on Shin’s definition, we have identified six Green Deals for analysis:

- The European Green Deal: Launched in 2019, the EGD aims to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 through decoupling economic growth from resource use, while ensuring a just transition across EU regions and industries [1].

- The US Inflation Reduction Act: Signed in 2022, the IRA is a legislative package focused on economic stabilisation and climate action, aiming to reduce carbon emissions by around 40% by 2030 from 2005 levels. It combines measures to reduce inflation with investments in clean energy, tax incentives and consumer energy savings to reduce carbon emissions[20].

- Japan’s Green Growth Strategy: Announced in 2020, the Green Growth Strategy targets carbon neutrality by 2050 through green innovation (hydrogen, offshore wind, digital technologies etc.) and green finance, focusing on supporting the private sector and cooperating internationally [21].

- South Korea’s Green New Deal: Launched in 2020 as part of a broader stimulus plan, South Korea’s Green New Deal aims to achieve net zero emissions by 2050, focusing on renewable energies, green infrastructure, technological innovation and the creation of green jobs [22].

- The UK’s Net Zero Strategy: Issued in 2021, the UK’s Net Zero Strategy commits to reaching net zero by 2050, with interim ‘carbon budgets’, focusing on the decarbonisation of seven key sectors, promoting green innovation, investing in renewable energy and creating green jobs [23].

- Australia’s Net Zero Plan: Announced in 2021, Australia’s plan aims for net zero emissions by 2050, with an emphasis on technological innovation and key enabling technologies (such as low-emissions hydrogen and carbon capture) to support emissions reductions or removals. It features six sectoral plans to reach net zero emissions across the economy [24].

In the sections that follow, these six Green Deals will be subject to comparison to determine whether the EGD is one-of-a-kind in its ambition and scope. The following section will examine the Green Deals’ green and funding ambitions. The third section will focus on the scope of the different strategies by evaluating (a) to what extent they touch on social policy and job creation and (b) their economic dimension through their emissions trading systems, followed by a concluding section.

II. The uniqueness of the EGD in its ambitions

A. Ecological and green targets

Except for the IRA, all the Green Deals studied share the long-term environmental target of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, in line with the Paris Agreement. Thus, this section focuses on interim targets to compare their level of ambition. Taking the 2030 interim targets as a benchmark, the EGD sets itself apart as the most ambitious Green Deal, particularly through the ‘Fit for 55’ package, which mandates a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 from 1990 levels [1]. This legally binding target spans all key sectors of the economy, including energy, transport and industry. In contrast, the US IRA aims for a 40% reduction by 2030, Japan targets a 46% reduction by 2030 from 2013 levels, and South Korea aims for a 24.4% reduction from 2017 levels [20][21][22]. These targets represent less aggressive cuts compared to the EU when considering the different baseline years.

The EGD has also set other targets besides emissions reduction, specifically on renewable energy and energy efficiency. Firstly, the Energy Efficiency Directive sets an EU-level target to improve energy efficiency by 11.7% by 2030. In addition, the revised Renewable Energy Directive sets a binding 2030 target of at least 42.5% renewable energy. In practice, Europe will aim to reach 45% of renewables in the EU energy mix by 2030 – doubling the existing share of renewable energy in the EU. In this regard, the Korean Green New Deal also has ambitious targets besides reducing its emissions, its primary goal being to drive a techno-industrial transformation. To support this transformation, the Green New Deal will significantly increase investment in renewable energy infrastructure. Solar and wind energy production, for example, is set to rise from 29.9 gigawatts (GW) to 42.7 GW by 2030, with renewable energy making up 21% of the national energy grid by that year – a considerable leap from the 6.5% share in 2019. This long-term ambition also includes a commitment to securing a 100% renewable energy future, starting with achieving 20% renewable energy production by 2030.

The UK’s Net Zero Strategy also stands out, targeting a 68% economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions reduction by 2030, compared to 1990 levels. This makes it one of the few plans to exceed the EU’s interim target. Moreover, the UK also matches the EU’s ambition to phase out polluting vehicles by 2035, as per the revised CO2 Standards Regulation. Indeed, the UK’s Zero Emission Vehicle mandate requires 80% of new cars and 70% of new vans to be zero-emission by 2030, ramping up to 100% by 2035. Considering this and given Australia’s Net Zero Plan lacks strong regulatory measures or concrete interim targets, we conclude the European Green Deal and the UK’s Net Zero Strategy demonstrate the highest level of ambition in their interim targets. Nonetheless, it is crucial to consider the scale of financial investment accompanying these plans, as funding will play a decisive role in determining which actors can truly achieve their ecological targets.

B. Funding ambitions

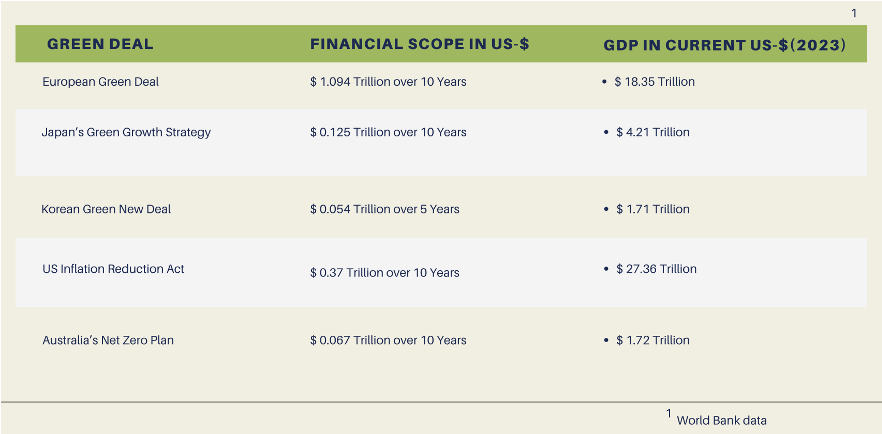

Comparing the financial scope of the different Green Deals is a daunting task. While the Commission committed itself to mobilising “at least EUR 1 trillion of private and public sustainability investments over the upcoming decade” [25], other nations have been less clear about the amount they aim to invest to reach their climate goals. Moreover, any Green Deal is just “an initial roadmap […] that will be updated as needs evolve and the policy responses are formulated” [1]. To make a comparison possible in the first place, this section will therefore not consider any updates made (see [25] for the latest details on EGD financing) but consider only the initial amount of money announced when the respective Green Deals were published. Per the Sustainable Europe Investment Plan, the initial commitment for the EGD amounts to EUR 1 trillion over 10 years [26].

Among the different Green Deals selected for this analysis, the IRA is the easiest to compare with the EGD, comprising USD 369 billion in incentives for energy and climate-related programmes in 10 years [27]. Given the greater size of the American economy, the IRA is thus not comparable to the scope of the EGD, even if it aims to trigger considerable additional private investment.

To assess the scope of the other Green Deals, more calculation is required. While the Korean Green New Deal amounts to KRW 73.4 trillion (KRW 42.7 trillion from the treasury) over 5 years [22][28], the Australian government speaks of an AUD 20 billion investment over the next decade, unlocking a further AUD 80 billion of private and public investment [24]. In the Japanese case, the government will invest JPY 2 trillion in a Green Innovation Fund over 10 years, to stimulate JPY 15 trillion of private R&D and investment. Furthermore, a tax initiative should stimulate another JPY 1.7 trillion of private investment [21]. If the different sums are added up for each country and then converted into USD, the following picture emerges:

Table 1: Financial Scope and GDP of Global Green Deals

Taking the countries’ GDP in current USD as a benchmark for comparison, we find that the EU invests each year approximately 0.6 to 0.7% of its GDP in the EGD, while figures amount only to approximately 0.3% of annual GDP investments for Australia and Japan. Korean investments reach 0.6% of annual GDP and thus a level comparable to the one of the EU. With the remarkable exception of South Korea, the EGD is thus also one of a kind in terms of its financial scope.

III. The uniqueness of the EGD in its scope

A. Social policy and job creation

A central aspect of the cross-sectoral approach that are Green Deals is their social dimension. Experts have underlined the emergence of a new wave of social risks due to climate change and climate policies, especially in low-income households [29]. Thus, each of the studied Green Deals includes social policies, to varying levels of depth.

A key aim of the EGD is to “leave no one behind” [1], funded through components such as the Just Transition Mechanism and the Social Climate Fund, with around 17% of its EUR 1 trillion investment target explicitly dedicated to social policies [26]. Yet, among the Green Deals analysed, only the Korean Green New Deal places a strong emphasis on reskilling for vulnerable communities. However, it lacks the scale and specificity of dedicated funds comparable to those of the EGD. The British and Australian strategies focus on broader job creation and upskilling within green sectors but without a targeted social equity framework. Japan’s Green Growth Strategy, meanwhile, centres on industrial transformation, with job creation as a secondary outcome rather than a primary social objective. On a comparable note, it is worth mentioning that the IRA’s precursor, the Green New Deal, had it passed in the US Senate, would have been the most comprehensive Green Deal on social matters. It very explicitly made the point that a Green Deal needs not only to protect those whose jobs will be lost to the green transition but to protect those most likely to be suffering the consequences of climate change itself, even going as far as to advocate for the need to “promote justice and equity by stopping current, preventing future and repairing historic oppression” [30].

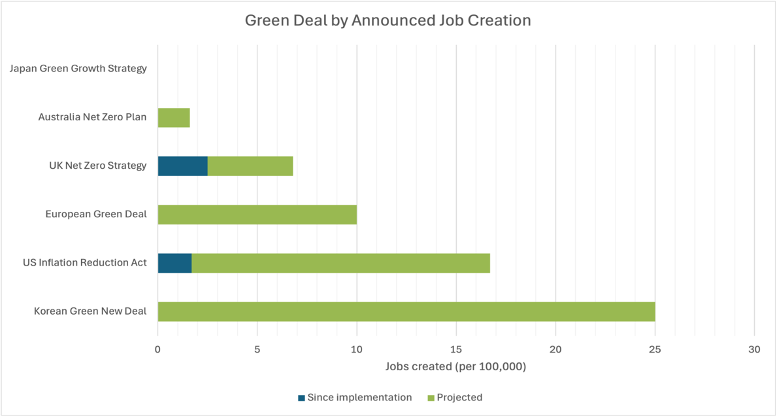

Except for the Japanese Green Growth Strategy, all the analysed Green Deals forecast a certain number of jobs to be created through their green transitions – again, to varying degrees:

Data: [31][32][33][34][35]

These figures are all anticipated by 2030, save for the Korean Green New Deal with a 2025 target. As the third most ambitious strategy in terms of job creation, the EGD stands at 1 million new ‘green’ jobs by 2030. It must be noted, however, that independent estimations extend far higher for these deals, reaching up to 9 million in the US and 25 million in the EU in the next decade [36][37]. While the Korean Green New Deal remains most ambitious in number and timeframe, no data has been released to confirm whether the country is on track to create 2.5 million new jobs by next year. Hence, with explicit, dedicated policies and funding for social support, alongside an ambitious job creation target, the EGD stands out among other Green Deals.

B. Emissions Trading Systems

Economic, growth and competitiveness considerations are more present than social aspects in all Green Deals that we studied. For instance, the Japanese deal did not plan for any job creation, but its focus point was the industry and economic growth. They all underline the importance of developing a competitive industry and investing in green innovation and technology.

To illustrate the economic dimension of the Green Deals around the world, we have chosen to study the corresponding Emissions Trading Systems (ETS). Portrayed as one of the main tools of the EGD [38], the European ETS dates to the early 2000s and is the oldest system still in force [39]. Frequently considered a model of success, it was the inspiration of many similar initiatives and, according to estimates of the International Carbon Action Partnership, 36 ETS are in place today, with another fourteen under development and a further eight under consideration [39].

While similar systems thus exist, many of them do not come close to the level of European ambition. The more recent Australian Safeguard Mechanism covers only slightly over 200 large facilities and relies on free allocation [39]. Japan is still in the exploratory phase of carbon pricing with two pilot systems in place on a sub-national level only [40] and, while it is true that the Chinese ETS is the world’s largest in terms of covered emissions, it covers merely CO2 emissions (no other greenhouse gases) and concerns the power sector exclusively [39]. Korea and the UK are comparatively closer to the European regime, with the Korean system exceeding the European ETS in terms of sectors concerned. However, if all aspects are considered, “the EU continues to be the largest system in force, in terms of trading volume and value” [39], rendering the EGD unique in this regard.

IV. Conclusion

In conclusion, by comparing the European Green Deal with similar strategies globally, it becomes clear that the EGD stands out in its ambition and scope. Its robust interim targets, substantial funding commitments and integration of social equity distinguish it from similar strategies worldwide. Unlike the other national-level Green Deals we analysed, the EGD is a supranational initiative, representing a unified effort to combat climate change like no other. Although some initiatives, such as the IRA or the Korean Green New Deal, exhibit impressive environmental commitments, none match the EGD’s scope, regulatory framework or collective regional vision, underscoring the EU’s leadership in sustainable transition efforts.

Bibliography

[1] European Commission. (2019). COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS – The European Green Deal. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52019DC0640

[2] Claeys, G., Tagliapietra, S., & Zachmann, G. (2019). How to make the European Green Deal work. Bruegel. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep28626

[3] Pianta, M., & Lucchese, M. (2020). Rethinking the European Green Deal: An industrial policy for a just transition in Europe. Review of Radical Political Economics, 52(4), 633–641. https://doi.org/10.1177/0486613420938207

[4] Lee-Makiyama, H. (2020). The European Green Deal: Reining in competition through regulation. European Centre for International Political Economy. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep29234

[5] Kougias, I., Taylor, N., Kakoulaki, G., Jäger-Waldau, A., & Monforti-Ferrario, F. (2021). The role of photovoltaics for the European Green Deal and the recovery plan. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 144, 111017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111017

[6] Milek, D. M., Andersen, M. H., & Marczinkowski, H. M. (2022). Unlocking the flexibility of Danish cogeneration units to support power system stability. Energies, 15(15), 5576. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15155576

[7] Sabato, S., & Fronteddu, B. (2020). A socially just transition through the European Green Deal? ETUI Research Paper – Policy Brief 2020.08. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3699367

[8] Lee, H. J., & Woo, J. (2020). Green New Deal policy of South Korea: Policy innovation for a sustainability transition. Sustainability, 12(23), 10191. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310191

[9] Galvin, R., & Healy, N. (2020). The Green New Deal in the United States: What it is and how to pay for it. Energy Research & Social Science, 67, 101529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101529

[10] Masoud Sajjadian, S. (2023). A critique on the UK’s net zero strategy. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, 56, 103003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2022.103003

[11] Agora Energiewende. (2020). The Korean Green New Deal: A roadmap to national decarbonisation and international climate leadership. https://static.agora-energiewende.de/fileadmin/Projekte/2022/2022-10_INT_Korea_Green_New_Deal/A-EW_280_Korean-Green-New-Deal_EN_WEB.pdf

[12] Lenain, P. (2023). Inflation Reduction Act versus Green Deal: Transatlantic divergences on the energy transition. Institut Français des Relations Internationales. https://www.ifri.org/fr/editoriaux/inflation-reduction-act-versus-pacte-vert-les-divergences-transatlantiques-sur-la

[13] O’Neill, M. (1997). Green parties and political change in contemporary Europe: New politics, old predicaments. Abingdon: Routledge.

[14] Friedman, T. L. (2007). A Warning from the Garden. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/19/opinion/19friedman.html

[15] United Nations. (2009). A Global Green New Deal. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=400&nr=670&menu=1515#:~:text=The%20Global%20Green%20New%20Deal,for%20green%20stimulus%20programs%20as

[16] Smol, M. (2022). Is the Green Deal a global strategy? Revision of the Green Deal definitions, strategies and importance in post-COVID recovery plans in various regions of the world. Energy Policy, 169, 1131152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2022.113152

[17] Sierra Club. (2024). What is the Green New Deal? Sierra Club. https://www.sierraclub.org/trade/what-green-new-deal

[18] European Council. (2019). European Green Deal – Consilium. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/green-deal

[19] Shin, D. (2020). The future direction of the Green New Deal, Korean Autonomy Association, Monthly Public Policy, 180.

[20] US Congress. (2022). H.R.5376 – Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text

[21] Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. (2021). Overview of Japan’s Green Growth Strategy Through Achieving Carbon Neutrality in 2050. https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/100153688.pdf

[22] Government of the Republic of Korea. (2020). Korean New Deal—National Strategy for a Great Transformation. https://english.moef.go.kr/skin/doc.html?fn=Korean%20New%20Deal.pdf&rs=/result/upload/mini/2020/07/

[23] UK Government. (2021). Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6194dfa4d3bf7f0555071b1b/net-zero-strategy-beis.pdf

[24] Australian Government. (2021). The Plan to Deliver Net Zero—The Australian Way. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/the-plan-to-deliver-net-zero-the-australian-way.pdf

[25] European Commission. (2024). Finance and the Green Deal—European Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/finance-and-green-deal_en

[26] European Commission. (2021). Finance and the Green Deal – European Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/finance-and-green-deal_en

[27] The White House. (2023). Building a Clean Energy Economy—A Guidebook to the IRA. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Inflation-Reduction-Act-Guidebook.pdf

[28] IEA. (2021). Korean New Deal—Digital New Deal, Green New Deal and Stronger Safety Net – Policies. IEA. https://www.iea.org/policies/11514-korean-new-deal-digital-new-deal-green-new-deal-and-stronger-safety-net

[29] Beaussier, A. L., Chevalier, T., & Palier, B. (2024). Qui supporte le coût de la transition environnementale ? Penser les inégalités face aux risques sociaux liés au changement climatique. Revue Française des Affaires Sociales. https://sciencespo.hal.science/hal-04699418v1/document

[30] Markey, E. & Ocasio-Cortez, A. (2023). Delivering a Green New Deal. https://www.markey.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/delivering_a_green_new_deal.pdf

[31] Australian Government. (2021a). Australia’s Long-Term Emissions Reduction Plan. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/australias-long-term-emissions-reduction-plan.pdf

[32] Climate Change Committee. (2023). A Net Zero Workforce. https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/CCC-A-Net-Zero-Workforce-Web.pdf

[33] European Commission. (2023). GREEN DEAL INDUSTRIAL PLAN – PLUGGING THE SKILLS GAP. https://year-of-skills.europa.eu/document/download/66dd95df-21b1-44f4-98c3-95af6addbdd8_en?filename=Skills4Green_factsheet_EN_07022024.pdf

[34] Korean Ministry of Economy and Finance. (2021). Government Announces Korean New Deal 2.0. https://english.moef.go.kr/pc/selectTbPressCenterDtl.do?boardCd=N0001&seq=5173

[35] Labor Energy Partnership. (2022). LEP Analysis Of The Inflation Reduction Act: Key Findings On Jobs, Inflation, And GDP Growth. https://laborenergy.org/fact-sheets/lep-analysis-of-the-inflation-reduction-act-key-findings-on-jobs-inflation-and-gdp/

[36] BlueGreen Alliance. (2022). 9 Million Jobs from Climate Action: The Inflation Reduction Act. https://www.bluegreenalliance.org/site/9-million-good-jobs-from-climate-action-the-inflation-reduction-act/

[37] Greens/EFA. (2023). Green Jobs: Successes and Opportunities for Europe. https://www.greens-efa.eu/files/assets/docs/greensefa_jobs_brochure_en_online-final_1.pdf

[38] European Commission. (2024). What is the EU ETS? – European Commission. https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets/what-eu-ets_en

[39] International Carbon Action Partnership. (2024). Emissions Trading Worldwide: Status Report 2024. https://icapcarbonaction.com/system/files/document/240522_report_final.pdf

[40] Nguyen, D. H., Chapman, A., & Farabi-Asl, H. (2019). Nation-wide emission trading model for economically feasible carbon reduction in Japan. Applied Energy, 255, 113869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.113869

[Table 1] World Bank. (2024). World Bank Open Data—GDP (current US$). https://data.worldbank.org