Energy and Climate Cooperation Between the European Union and Japan – Time to Change Gears

21 March 2025

The Geopolitics of the European Green Deal: From Fragile to Strategic Dependencies?

31 March 2025By Xavier EVANS, Marlena DZIEKANOWSKA, Dzhoro IVANOV, Marion BEAULIEU, Bára KOŠŤÁLOVÁ & Maxime SASPORTES

I. Introduction

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is a comprehensive piece of US federal legislation signed into law in 2022. Despite the name implying a predominant focus on inflation, the Act actually features three broad sets of measures: tax reforms [1], healthcare policy changes [2], and most importantly for this paper, extensive climate- and energy-related provisions and subsidies [3]. Regarding the latter, the IRA has been touted as the most ambitious climate legislation in US history [4]. It is estimated to inject almost $400b into climate change mitigation through a mixture of loans, grants, and (consumer and corporate) targeted tax incentives to fund clean electricity, energy transmission, manufacturing, and transportation amongst others [5]. More than half of the projected funds are made available through transferable tax credits, of which corporations are by far the biggest beneficiaries [6]. Consequently, the IRA’s incentive structure is designed to catalyse private investment into the sectors of the US economy that are key to facilitating the energy transition [7].[1 See note]

The IRA does not institute formal mandated targets but is expected to result in reductions to US greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of between 43% and 48% by 2035 [9]. While this is insufficient to meet US commitments to the Paris Agreement, the IRA is expected to double the rate of emissions reduction [10], bringing the US more closely in line with its pledge to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Hence, many have argued that the IRA represents a successor and/or alternative to the Green New Deal, which was advanced by the progressive wing of the Democratic Party, but failed to gain traction amongst the wider political spectrum [11]. Determining whether the IRA reaches the breadth and depth of policy action required to be considered a Green Deal is the main purpose of this paper.

There are currently no large- and medium-scale comparative studies of green deals, and the few papers that review multiple green deals are heavily biased towards the unlegislated US Green New Deal proposal [12] and do not cover the IRA. In order to assess whether the IRA can truly be regarded as a Green Deal, this paper will compare it to what is arguably the only example of a successful implementation of a full-scale Green Deal – the European Green Deal (EGD) established by the European Union (EU). This allows for a practical analysis of the IRA scope and, rather than being limited to theoretical comparisons.

The EGD tackles four main sectoral areas that will frame our discussion of the IRA: the energy transition, decarbonisation of the non-energy economy, new green growth industries, and finally biodiversity and agricultural policies. For each of these sectors, the EGD implements four main policy tool approaches: regulation, tax policy, direct investment, and international trade and investment. For each of the sectors and mechanisms identified, we will present the framework designed by the EGD and appraise the IRA compared to this benchmark.

II. Sectoral analysis

a) Securing the Energy Transition

The EGD has a comprehensive approach to transforming the European energy sector, with two focus areas. The first is the acceleration of renewable energy deployment. The current binding target for renewables stands at 42.5% by 2030 but aiming for 45%, as set out in the 2023 REDIII [13]. The revised directive also sets sector-specific targets including a binding target of 42% of renewable hydrogen in total hydrogen consumption by 2030 for the industrial sector.

The IRA provides a similarly complete framework to support the energy transition. Substantively, the IRA includes tax credits for the production of electricity from renewable sources, for electricity produced through nuclear power plants, and for the production of clean hydrogen [14]. It also expands the remit of the Loans Program Office (LPO) enabling the establishment of a $3.6b loan guarantee programme for innovative clean energy technologies [15]. Further, the package provides the Environmental Protection Agency with a $27b Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund for clean energy and climate projects [16]. According to the IMF, these measures could increase the share of renewables in the USA’s energy mix by around 19 percentage points by 2030 [17]. Considering renewables already accounted for 21.1% of American power generation in 2022, the IRA targets are closely aligned with that of the EGD’s 42.5% objective [18].

The second area of focus in the EGD is improvements to energy efficiency. The latest 2023 revision of the Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) sets out a target of 11.7% reduction in energy consumption by 2030 [19]. The EGD also induced a revision of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) in 2024, aiming to decrease the average energy performance of the national residential building stock by 16% by 2030 (compared to 2020 levels) [20].

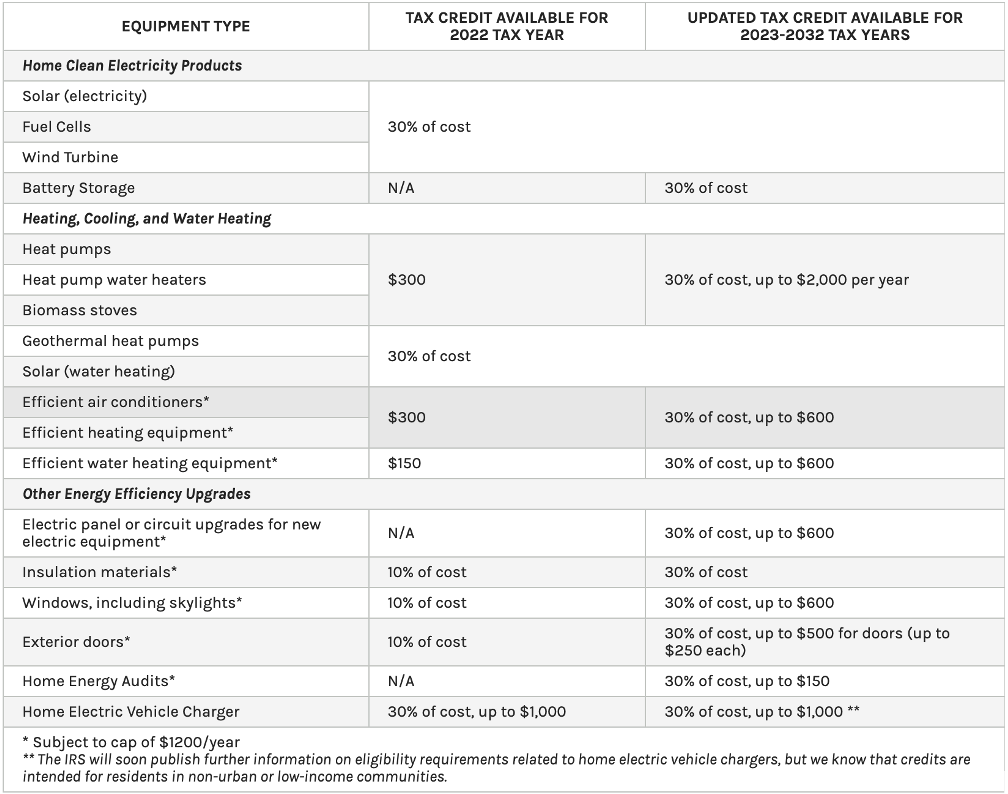

Regarding energy efficiency, the IRA makes provisions for tax credits and loans targeted at improving energy efficiency in existing homes and new constructions [21]. Examples of these programmes include the Energy Efficient Home Improvement Credit [22], Home Energy Tax Credits [23], and Residential Clean Energy Credit [24], aiming to incentivise citizens to invest more into energy-efficient improvements of their houses. A summary of tax credits available to homeowners under the IRA is presented below:

Figure 1: credits for energy efficiency offered by the IRA [25]

Ultimately, both the EGD and the IRA target the development of renewables and increasing energy efficiency at similar levels of ambition and scope.

b) Decarbonisation of the non-energy economy

While the energy sector is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, the decarbonisation pathway is relatively straightforward. In comparison, many industrial sectors of the economy have significant emissions profiles outside of direct energy consumption. To address this challenge, the EGD develops two core policy focus areas.

The first is a revolution in the way industry currently operates, spearheaded by the Circular Economy Action Plan, which aims to reduce the pressure on natural resources and lead to sustainable growth. It focuses on addressing the entire life cycle of products in sectors with high potential for circularity, such as electronics, batteries, packaging, plastics or textiles [26]. By contrast, the notion of circular economy is not explicitly referred to in the IRA. The Act does include the notion of recycling critical materials or clean energy equipment [27], but compared to the EGD framework, it remains very light on a truly circular approach to industrial supply chains.

The second focus of the EGD is the disproportionate impact of climate change action on vulnerable communities. The Just Transition Mechanism allocates around €55b from 2021 to 2027 and is directed towards regions with the most carbon-intensive production or with the most people working in fossil fuels, where it facilitates employment opportunities and re-skilling services. [28] For its part, the IRA also prioritises investments in environmental justice, including grant programs promoting public health, the fight against pollution and the revitalisation of marginalised communities. [29] One example of such policies is the Environmental and Climate Justice Program creating funding schemes and technical support for environmental and justice activities in underserved areas [30], and the Justice40 initiative to redirect green investment flows to disadvantaged communities [31].

The IRA undoubtedly focuses on the decarbonisation of the non-energy economy, however, the scope it undertakes seems to be narrower in its focus, especially when it comes to the promotion of a circular economy.

c) New green growth industries

Crucial to the EGD project is a belief in economic growth as a driver of environmental objectives. The EGD clearly establishes a framework for the development of new green growth industries, which simultaneously provide economic activity while out-competing conventional, dirty industries, and providing a clear economic incentive for an economic realignment to prefer green products. The EGD establishes the regulatory framework to develop these industries through the Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA). Beyond that, the scope of European industrial policy through the EGD is extensive, tackling input technologies like clean hydrogen, consumer alternatives like electric vehicles (EVs), and industrial alternatives such as green steel.

The political philosophy behind the IRA draws heavily from the same intellectual tradition as the EGD, looking to incentivise the development of American green industries that provide economic stimulus and out-compete conventional industries as well as foreign, green industries, notably from Europe or China [32].

In the hydrogen sector, the IRA offers substantial tax credits to incentivize both green and blue hydrogen production, aiming for a 40% reduction in production costs [33]. This emphasis on domestic production is complemented by specific emissions performance criteria that must be met to qualify for financial support.

For the EVs sector, the IRA adopts a more market-driven approach, offering substantial tax credits for the purchase of new and used EVs [34]. This framework not only includes specific requirements for battery sourcing and vehicle assembly but also promotes domestic production [35].

In the industrial sector, the IRA looks to accelerate the development of a clean steel sector, concentrating on immediate emission reductions and bolstering domestic production. The Act sets an ambitious target of a 50-52% decrease in carbon emissions by 2030, compared to 2005 levels [36].

The headline ambitions of the IRA generally match those of the EGD, however they lack the same scope and depth. The American approach is generally focused on the higher end of the technology readiness level, where businesses have existing turnover and tax breaks can have a genuine impact. Where in Europe, the EGD provides government support at all levels of technology development and commercialisation, the IRA is more limited – outside the LPO which is focused on energy technologies only, the US is more reliant on private venture capital to find and develop the next technological breakthroughs required for future green growth industries.

The EGD is also a longer-term project, recognising that many green growth industries may take decades to mature, and establishing the regulatory framework to support that time horizon, through long-term, graduated targets. In contrast, The IRA’s financial incentives are designed to stimulate consumer demand and bolster local manufacturing, with minimal target-setting or long-term planning for these green growth industries through to 2050.

d) Biodiversity and agricultural policies

The final section of the EGD framework is biodiversity and agricultural policies, covered by the 2030 Biodiversity Strategy, the Zero Pollution Act (ZPA), and the ‘Farm to Fork’ initiative. The EU 2030 Biodiversity Strategy is a comprehensive package aiming to restore the EU’s ecosystems by 2030 [37], while the ZPA aims to reduce air, water, and soil pollution to zero by 2050 [38].

Turning to agriculture, the ‘Farm to Fork’ programme aims to increase the resilience of the EU food systems and ensure environmentally friendly agricultural practices [39]. The package is set to transform the entire supply chain by reducing the use of pesticides and fertilisers, improving animal welfare and reversing biodiversity loss caused by harmful farming methods.

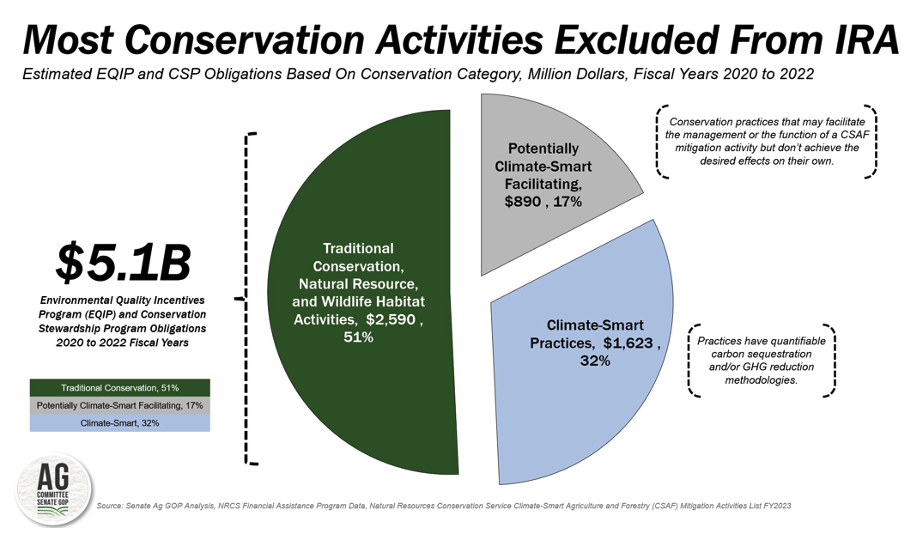

In this area, the IRA has a less comprehensive approach to safeguarding environmental outcomes. The package includes a $20b envelope targeted at mitigating the impact of agriculture on climate change and biodiversity loss [40]. The most important programmes funded by the IRA include the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), which receives $8.45b to assist farmers in developing conservation practices. The Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) receives $6.75b to continue its activities in natural resource management and protection on agricultural lands. $3.25b is directed to the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) to support farmers implementing organic farming methods and practices that ensure biodiversity conservation on their land [41].

Ultimately, the scope of the IRA regarding agriculture and biodiversity conservation is not comparable to that of the EGD. Firstly, the funds supported by the IRA are targeted at “climate-smart agriculture and forestry mitigation activities” (CSAF) as defined by the US Department of Agriculture [42]. However, it is estimated that CASF activities only represent 49% of conservation practices identified by the EQIP and CSP, as shown below:

Figure 2: conservation activities excluded from the IRA [43]

The remaining protection activities are hence excluded from receiving funding under the IRA’s agricultural schemes, thereby restricting its transformative impact.

Secondly, the IRA does not make provisions for comprehensive biodiversity protection as it restricts its scope to sustainable agriculture. The IRA’s activities thereby exclude other biodiversity challenges, such as marine ecosystem and wetland protection [44]. Furthermore, there are no comparable habitat or species protection targets to frame the provisions of the IRA, as opposed to the ones set out by the EGD Biodiversity Strategy.

III. Mechanisms approach

a) Regulation

The primary policy function of the EGD is to set the regulatory framework within which Europe can transition away from fossil fuels and reach net zero. The European Climate Law enshrines climate neutrality by 2050 (and 55% emissions reduction by 2030) in law, establishing the legal framework by which the EU can be held accountable by the European Court of Justice if the target is not met. [45] The EGD also sets non-binding targets across the European economy, for example on energy transition outcomes through the Renewable Energy Directive [46], infrastructure development through the Connecting Europe Facility [47], or green growth industries through the Critical Raw Material Act [48]. While these targets are not legally enforceable, they provide clear objectives for policymakers and private sector actors to work towards. Finally, at a micro level, the EGD also establishes new rules to increase the sustainability of a range of different sectors, including timber products through the EU Deforestation Regulation [49], corporate supply chains through the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive [50], and aviation fuels through the Sustainable Aviation Fuels Regulation [51].

The IRA, by contrast, features no binding provisions whatsoever, limiting its direct impact on climate change mitigation to aspirational goals. There are considerable reservations on the part of many environmental policy experts that the IRA’s ‘all carrots, no sticks’ approach will be enough to put the US firmly on the sustainable growth track. The models that showcase the legislation’s prospective impact on GHG emissions are built around assumptions of price-induced behavioural changes that are, at best, educated guesses [52].

b) Tax policy

The one area where the EGD has not implemented its full potential as a Green Deal package is in tax policy, given the EU only has the legal basis for coordination competence. The scope of EU action is inherently limited and has been largely confined to including the maritime sector in the emission trading system (ETS 1), and introducing a separate emission trading system covering buildings, road transport and several additional sectors (ETS 2) [53]. Attempts to revise the Energy Taxation Directive have stalled. However, the framework is clear: increase taxation on environmentally damaging products and behaviours, and provide tax breaks to change the economic incentives in favour of a net zero future.

The IRA, for its part, does not raise any new climate-related taxes, reflecting the inflation-induced cost of living crisis that was facing US consumers at the time of the bill’s passage, and the political unpopularity of new taxes. It should however be noted that several US states had previously adopted cap-and-trade systems to put a price on carbon emissions, such as in California and in a collaborative effort by Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states [54].

Instead of either legally binding targets or a carbon tax policy, the IRA has been left to rely almost exclusively on tax breaks for activities that accelerate the transition to climate neutrality. The IRA establishes a 10-year programme for consumer and investment tax credits, primarily targeting industrial and manufacturing industries, with some provisions for consumers, particularly in a tax break for the purchase of EVs. Importantly, complying with the legal prerequisites is relatively straightforward for both companies and individuals, which means that benefitting from the available incentives is much easier than is usually the case in the EU [55]. Furthermore, the investment tax credits under the IRA can be sold once acquired. This combination of flexibility, simplicity and predictability is essential to giving sustainable practices and products a structural advantage to scale [56]. While in the short term, the IRA will indeed channel sizable investment into clean industries, whether said industries will continue to grow and be economically viable once the subsidies have come to an end is yet to be seen [57].

c) Direct investment

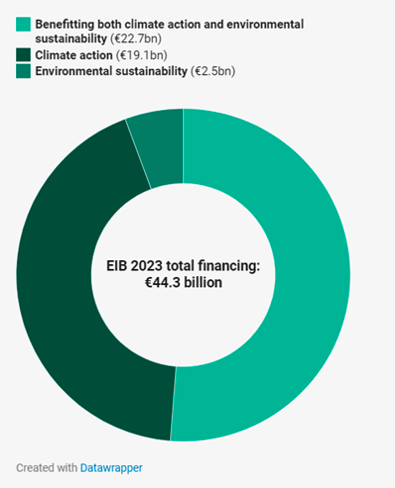

In addition to marshalling private capital to invest in the transition, the EGD envisages mobilising at least €1000b in green investments over the decade. Many institutions are involved in implementing this plan. Firstly, The European Investment Bank (EIB) plays a key role in the EGD by financing climate and sustainability projects, with 60% of its financing dedicated to environmental initiatives by 2023. The REPowerEU program supports the Green Deal by investing in divestment from Russian gas supply, financed by the Recovery and Resilience Facility. Another instrument, the European Hydrogen Bank [58], launched in 2022, subsidises hydrogen production on a per-unit basis. Similarly, the Innovation Fund directly finances the energy transition of industries, mobilising more than €500m.

Figure 3: EIB climate and environmental sustainability financing [59]

For its part, the IRA does not offer a wide range of tools in the form of direct investments, preferring tax breaks as an indirect public investment mechanism. There are some direct investments, the Act provides the US Environmental Protection Agency with some $1.36b to help small oil and gas operators reduce their emissions by encouraging the adoption of innovative technologies. [60] In addition, $350m of the fund will be used to finance the permanent closure of oil wells.

The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund has a further $7b to be invested in the competitiveness of low-income communities, in order to encourage them to equip themselves with non-emitting technologies. Similarly, investments in biofuels were boosted by $10b, investments in energy infrastructure by $5b, and investments in environmentally responsible building labels by $100m. [61][62][63] Finally, as discussed above, some specific measures deploy direct capital to develop initiatives to decarbonise and protect biodiversity in the agricultural space.

Ultimately, the IRA does not commit much public money directly to the investment in a future green economy, preferring indirect investment through tax breaks, which defer investment decisions to the private sector. This again reflects the political reality of American approaches to government spending, and constrains the IRA as a true Green Deal.

d) International relations and trade

Climate change is a truly global challenge, and the impact of climate policy is generally constrained within the jurisdiction of the legislative authority passing the bill. However, the EGD remains ambitious, seeking to export its regulatory power to develop international impact from its regional climate ambitions and help third countries make the transition to sustainable energies while limiting the impact on their own growth [64].

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism imposes a carbon tax on imports from 2026 to prevent “carbon leakage” where companies relocate emissions-heavy production outside the EU [65]. The Global Gateway strategy, launched in 2021, aims to mobilise up to €300b in sustainable investments by 2027, focusing on regions like Africa, Asia, and Latin America supporting climate and energy projects to rival China’s Belt and Road Initiative [66][67]. Additionally, the EU promotes Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) to assist developing countries in transitioning to clean energy, with an initial $1b contribution to South Africa in 2021 [68].

By contrast, the IRA is much less oriented towards international trade. In fact, the IRA does not integrate explicit measures related to it. On the contrary, the law has been strongly criticised for its domestic character, implying a denial of the global nature of climate change [69].

IV. Conclusion

The Inflation Reduction Act is a massive policy package which is in large part aimed at tackling the truly monumental challenge of climate change. This paper has analysed the extent to which it can, however, be considered a true Green Deal. Using the European Green Deal as the best standard for practical, implemented policy in a major jurisdiction, we find that the IRA is not truly a Green Deal. While many of the same sectors are addressed, and it remains faithful to the green growth philosophy that drives the EGD, its mechanisms are constrained by political forces that limit its breadth. The IRA is overly reliant on tax breaks as a form of private sector stimulus and does not establish meaningful targets or regulate industries to force them to operate more sustainably. The IRA remains a formidable climate policy, however, it is not a true Green Deal.

Notes

[1] Notably, the aforementioned figures are only preliminary estimates, as the total volume of tax credits will be ultimately determined by market demand and is de facto uncapped [8].

References

- Scheinert T. (2023). EU’s response to the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Directorate-General for Internal Policies, Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2023/740087/IPOL_IDA(2023)740087_EN.pdf

- Kleimann D., Poitiers N., Sapir A. Tagliapietra, S., Véron N., Veugelers, R., Zettelmeyer, J. (2023, February 2023). How Europe should answer the US Inflation Reduction. Bruegel. https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/how-europe-should-answer-us-inflation-reduction-act

- Ibid.

- Bistline, J. et al. (2023). Emissions and energy impacts of the Inflation Reduction Act. Science 380(6652), 1324–1327. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg3781

- Badlam, J. et al (2022, October 24). The Inflation Reduction Act: Here’s what’s in it. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/the-inflation-reduction-act-heres-whats-in-it

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Elkerbout, M., Righetti, E. & Egenhofer, C. (2023, December 5) Different roads, Aligned Goals: How and why the Inflation Reduction Act and EU green industrial policies differ in supporting cleantech deployment. CEPS. https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/different-roads-aligned-goals/

- Bistline, J. et al. (2023). Emissions and energy impacts of the Inflation Reduction Act. Science 380(6652), 1324–1327. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg3781

- Ibid.

- Meaney, T. (2022). Fortunes of the Green New Deal. New left 138. 79–103 https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii138/articles/thomas-meaney-fortunes-of-the-green-new-deal

- Green, F. (2024) Green New Deals in comparative perspective. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Climate change 15(4). Article e885 https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.885

- European Commission (n. d.). Renewable Energy Directive. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/renewable-energy/renewable-energy-directive-targets-and-rules/renewable-energy-directive_en

- European Parliamentary Research Service (2023). EU-US Climate and energy relations in light of the Inflation Reduction Act. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2023/739300/EPRS_BRI(2023)739300_EN.pdf

- US Department of Energy. (n. d.). Clean Energy Financing. Loans Programs Office. Retrieved October 30, 2024, from https://www.energy.gov/lpo/clean-energy-financing

- EPA Press Office (2024, August 16). EPA Awards $27B in Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund Grants to Accelerate Clean Energy Solutions, Combat the Climate Crisis, and Save Families Money. EPA. https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-awards-27b-greenhouse-gas-reduction-fund-grants-accelerate-clean-energy-solutions

- Voigts S. & Paret A-C. (2024). Emissions Reduction, Fiscal Costs, and Macro Effects: A Model-based Assessment of IRA Climate Measures and Complementary Policies. IMF Working Papers. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2024/02/09/Emissions-Reduction-Fiscal-Costs-and-Macro-Effects-A-Model-based-Assessment-of-IRA-Climate-544749

- International Energy Agency (n. d.). Energy System of United-States. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://www.iea.org/countries/united-states

- European Commission (n. d.). Energy Efficiency Directive. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-efficiency/energy-efficiency-targets-directive-and-rules/energy-efficiency-directive_en

- European Commission (n. d.). Energy Performance of Buildings Directive. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-efficiency/energy-efficient-buildings/energy-performance-buildings-directive_en

- European Parliamentary Research Service (2023). EU-US Climate and energy relations in light of the Inflation Reduction Act. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2023/739300/EPRS_BRI(2023)739300_EN.pdf

- IRS (2024). Energy Efficient Home Improvement Credit. https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/energy-efficient-home-improvement-credit

- IRS (2024). Home energy tax credits. https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/home-energy-tax-credits

- IRS (2024). Residential Clean Energy Credit. https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/residential-clean-energy-credit

- U.S. Department of Energy (2022) Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 – What it means for you. https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/articles/inflation-reduction-act-2022-what-it-means-you

- European Commission (n. d.). Circular economy action plan. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/circular-economy-action-plan_en

- The White House. (2023). Building a clean energy economy: A guidebook to the Inflation Reduction Act’s investments in clean energy and climate action. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Inflation-Reduction-Act-Guidebook.pdf

- European Commission (n. d.). The Just Transition Mechanism: making sure no one is left behind. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/finance-and-green-deal/just-transition-mechanism_en

- The White House. (2023). Building a clean energy economy: A guidebook to the Inflation Reduction Act’s investments in clean energy and climate action. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Inflation-Reduction-Act-Guidebook.pdf

- EPA (2023). Inflation Reduction Act Environmental and Climate Justice Program. https://www.epa.gov/inflation-reduction-act/inflation-reduction-act-environmental-and-climate-justice-program

- The White House (2022). Justice40. https://www.whitehouse.gov/environmentaljustice/justice40/

- Elkerbout, M., Righetti, E. & Egenhofer, C. (2023, December 5) Different roads, Aligned Goals: How and why the Inflation Reduction Act and EU green industrial policies differ in supporting cleantech deployment. CEPS. https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/different-roads-aligned-goals/

- Munteanu, B. (2024). The Policies of the Green Industrial Transition from Geopolitical Viewpoints and Their Potential Implications for Geoeconomic Fragmentation. A Comparative Approach of EU, USA, and China.” Romanian Journal of European Affairs 24 (1), 86–106. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4874381

- U. S. Department of Energy (2022). Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. https://www.energy.gov/lpo/inflation-reduction-act-2022

- Voigts S. & Paret A-C. (2024). Emissions Reduction, Fiscal Costs, and Macro Effects: A Model-based Assessment of IRA Climate Measures and Complementary Policies. IMF Working Papers. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2024/02/09/Emissions-Reduction-Fiscal-Costs-and-Macro-Effects-A-Model-based-Assessment-of-IRA-Climate-544749

- U. S Department of Energy (2022). Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. https://www.energy.gov/lpo/inflation-reduction-act-2022

- European Commission (n. d.). Biodiversity strategy for 2030. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/biodiversity-strategy-2030_en

- European Commission (n. d.). Zero Pollution Action Plan. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/zero-pollution-action-plan_en

- European Commission (n. d.). Farm to Fork Strategy. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://food.ec.europa.eu/document/download/472acca8-7f7b-4171-98b0-ed76720d68d3_en?filename=f2f_action-plan_2020_strategy-info_en.pdf

- Friends of the Earth (2022). The Climate & Agriculture provisions of the IRA. https://foe.org/blog/reviewing-ira/

- Ibid.

- United States Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry (2023). Inflation Reduction Act Leaves Farmers and Traditional Conservation Programs Behind. https://www.agriculture.senate.gov/newsroom/minority-blog/inflation-reduction-act-leaves-farmers-and-traditional-conservation-programs-behind

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- European Commission (n. d.). European Climate Law. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/european-climate-law_en

- European Commission (n. d.). Renewable Energy Directive. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/renewable-energy/renewable-energy-directive-targets-and-rules/renewable-energy-directive_en

- European Commission (n. d.) Connecting Europe Facility. European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://cinea.ec.europa.eu/programmes/connecting-europe-facility_en

- European Commission (n. d.). Critical Raw Materials Act. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/raw-materials/areas-specific-interest/critical-raw-materials/critical-raw-materials-act_en

- European Commission (n. d). Regulation on Deforestation-free Products. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/forests/deforestation/regulation-deforestation-free-products_en

- European Commission (n. d). Corporate sustainability due diligence. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://commission.europa.eu/business-economy-euro/doing-business-eu/sustainability-due-diligence-responsible-business/corporate-sustainability-due-diligence_en

- European Commission (n. d.). ReFuelEU Aviation. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://transport.ec.europa.eu/transport-modes/air/environment/refueleu-aviation_en

- Storm, S. (2022, September 15) The inflation reduction act (IRA): A brief assessment, Institute for New Economic Thinking. https://www.ineteconomics.org/perspectives/blog/the-inflation-reduction-act-ira-a-brief-assessment

- Council of the EU (2023, April 25). ‘Fit for 55’: Council adopts key pieces of legislation delivering on 2030 climate targets. European Council, Council of the European Union. Press release. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/04/25/fit-for-55-council-adopts-key-pieces-of-legislation-delivering-on-2030-climate-targets/

- Schmalensee, R. & Stavins, R.N., (2017). Lessons Learned from Three Decades of Experience with Cap and Trade. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 11. 59–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/rew017

- Elkerbout, M., Righetti, E. & Egenhofer, C. (2023, December 5) Different roads, Aligned Goals: How and why the Inflation Reduction Act and EU green industrial policies differ in supporting cleantech deployment. CEPS. https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/different-roads-aligned-goals/

- Goodell, J. (2022, August 16) The Biden climate bill: Will it save us? Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-features/climate-change-inflation-reduction-act-biden-enough-1397313/

- Elkerbout, M., Righetti, E. & Egenhofer, C. (2023, December 5) Different roads, Aligned Goals: How and why the Inflation Reduction Act and EU green industrial policies differ in supporting cleantech deployment. CEPS. https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/different-roads-aligned-goals/

- European Commission (n. d.). European Hydrogen Bank. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-systems-integration/hydrogen/european-hydrogen-bank_en

- European Investment Bank (n. d.). Climate Action Explained. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://www.eib.org/en/projects/topics/climate-action/explained

- Text – H.R.5376 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, § 60113.(2022, August 16). https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text

- Text – H.R.5376 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, § 60103. (2022, August 16). https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text

- Text – H.R.5376 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, § 60108. (2022, August16). https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text

- Text – H.R.5376 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, § 50144. (2022, August 16). https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text

- Koch, S. & Keijzer, N. (2021). The External Dimensions of the European Green Deal: The Case for an Integrated Approach. Briefing Paper. https://doi.org/10.23661/BP13.2021

- European Commission (n. d.). Carbon leakage. Retrieved October 30, 2024. https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets/free-allocation/carbon-leakage_en

- Bilal, S. & Teevan, C. (2024, June 10). Global Gateway: Where now and where to next? ECDPM. https://ecdpm.org/work/global-gateway-where-now-and-where-next

- Heldt, E. C. (2023). Europe’s Global Gateway: A New Instrument of Geopolitics. Politics and Governance 11 (4). 223–234. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v11i4.7098

- Earsom, J (2024). Fit for Purpose? Just Energy Transition Partnerships and Accountability in International Climate Governance. Global Policy 15 (1). 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.13324

- Bigger, P., et al. (2022). Inflation Reduction Act: The Good, The Bad, The Ugly. The Climate and Community Project. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.10145.48481