Innovative Financing Schemes

23 August 2023

THE FUTURE OF EUROPEAN ENERGY EFFICIENCY POLICIES: OPTIONS AND UPDATES

23 August 2023By Alice Latella

Many are the arguments and narratives beyond energy efficiency (EE). What is important to take into account is that EE delivers a multitude of benefits to a multitude of stakeholders ranging from energy savings, social, economic, and environmental benefits to macroeconomic benefits (IEA, 2014). The aim of this paper is to analyse what are the broader macroeconomic benefits of EE, which refer to the fact that EE can have a positive impact across the whole economy, and try answer to the following question: should energy efficiency policy increase the competitiveness of our economies and comfort for citizens or instead promote a more sustainable way of living based on degrowth aspects and energy sufficiency? In part 1, the “traditional” macroeconomic impacts of EE will be explored, looking at the effect of EE on GDP and employment levels. In part 2, the concept of the rebound effects will be introduced, in order to present the limitations and shortcomings of the traditional approach to EE (i.e. growing with less energy). In part 3, we will propose a challenging perspective of EE and argue that EE policies should try to promote a more sustainable way of living based on degrowth and energy sufficiency, through the pursue of less energy consumption and production. Lastly, we will give some recommendations on how policies could successfully accompany such a move.

- Traditional macroeconomic impacts of EE: increase the competitiveness of our economy.

The discussion around the multiple benefits of energy efficiency (EE) starts with its macroeconomic benefits meaning that, by reducing energy consumption and thus energy costs, EE gains can lead to an increase in economic output, increase in employment levels but also decrease in energy prices, improving the overall competitiveness of our economies. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), these macroeconomics impacts of EE are driven by two main factors: investment effects and energy demand reduction effects, as we can see in the figure 1 below (IEA, 2014). On one side, EE investments in sectors producing EE goods and services have the direct effect to higher production levels and employment in those sectors (IEA, 2014). On the other side, energy demand reductions and cost savings thanks to EE improvements could lead to higher disposable income for households, who may start to consume more or spend their income in other goods and services (spending effect). Moreover, cost savings could lead to higher profits for businesses/producing sectors, who would reinvest their savings (reinvestment effect) or pass through the low production price to consumers (price effect) (IEA, 2014). As a result, energy demand reductions also contribute to increase economic growth and employment levels but also to reduce energy prices and improve energy security.

Figure 1. Macroeconomic impact and macroeconomic effects of EE (Source: IEA, 2014)

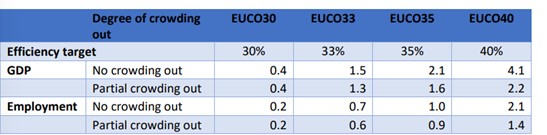

To quantify the overall impact of EE on the GDP and employment, the European Commission has developed 4 scenarios characterised by 4 different EE targets and their respective impact on GDP and employment levels, presented in figure 2 below. In the most ambitious scenario, with 40% EE target in 2030, GDP would increase by 4.1 % and employment by 2.1 % by 2030. In the least ambitious scenario with 30% EE target in 2030, GDP would rise by 0.4 % and employment by 0.2% by 2030. The table below also shows the effects of crowding out which refer to “capacity constraints on the levels of production that can be achieved” thus the scenarios also assume that there can be a certain limit to how much production can increase (partial crowding out) (European Commission, 2017, p 117).

Figure 2: GDP and employment impacts of EE, EU28 (Source: European Commission, 2017)

- The rebound effects and the limitations of the traditional approach to EE

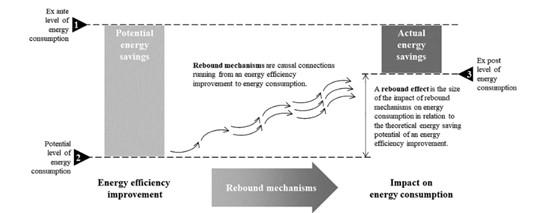

Energy efficiency is often justified and supported by policymakers for its positive spill overs on the whole economy and for the increase in the comfort of the society thanks to higher disposable income for households and higher profits for businesses, as explained above. It is important however to consider that EE can also lead to rebound effects, which means that “improved efficiency is used to access more goods and services rather than to achieve energy demand reduction” (IEA, 2014, p 38). Rebound effects refer indeed to an increase in energy consumption because of the above-mentioned macroeconomic effects, for example the spending effect or investment effect, and, as a consequence of that, the desired energy savings and emissions savings are limited, as shown in Figure 3 below. Rebound effects can be of two types: direct rebound effects, which refer to the fact that EE improvements lead to higher consumption for the same good and services, and indirect rebound effects, which refer to the fact that higher EE gains in one sector leads to higher consumption level in other sectors or in other goods and services (European Commission, 2017).

Figure 3: Rebound Mechanisms (Source: Lange et al., 2021)

According to the IEA, rebound effects can generate social and economic welfare as citizens and businesses can see their income and profits increased (IEA, 2014). However, the main issue underlined in this paper is that rebound effects, either small or large in size, direct or indirect, could instead undermine the ambition of EE to reduce overall energy consumption and thus cut emissions. In fact, “while rebound effects reflect better economic and social outcomes, they may lead to worse environmental outcomes, thus representing a trade-off between benefits” (European Commission, 2017, p 14). EE can indeed result in negative environmental impacts and lead to higher emissions due to the increase in energy consumption caused by the rebound effects. The main limitation of the traditional approach of EE of “growing with less energy” is indeed the “growing” part: households will continue to consume more and more, and businesses will continue to produce more and more due to the rebound effects. Therefore, this traditional approach risks continuing supporting a system based on unlimited, unsustainable and excessive energy consumption and production, and continuing to give the priority to economic growth and not to the environment.

This is why it is worth clarifying that if the goal of policies is continuing to boost economic growth,then EE should increase the competitiveness of our economies and comfort for citizens. If on the contrary the goal is to decrease emissions and limit the rebound effects of EE, then it is inevitable that policies should promote a new, more challenging approach based on degrowth and energy sufficiency, as we will describe in the next section. We argue that our approach to growth should completely change, because it is exactly this growth model the first cause of environmental degradation, as it looks only at increasing the productivity based on monetary values and disregards the environmental and ecological elements as they don’t bring any monetary values to the economy (Parrique, September 2022).

- The need for a challenging perspective on EE: degrowth and energy sufficiency

When looking at the literature on the macroeconomic impacts of EE and at the EE scenarios for example of the IEA and the European Commission, the concept of degrowth is almost absent. Degrowth is still not considered to a be a macroeconomic benefit of EE or a means to ensure a more sustainable way of living in the EE policymaking. Industrialised countries have always considered EE as the driver of economic growth but not of degrowth (Keyßer and Lenzen, 2021). In an article in the journal Nature Communications, degrowth is defined as “equitable downscaling of throughput [that is the energy and resource flows through an economy, strongly coupled to GDP], with a concomitant securing of wellbeing” (Keyßer and Lenzen, 2021, p.2). In his book “ Ralentir ou Périr”, Parrique defines degrowth as “ réduction de la production et de la consommation pour alléger l’empreinte écologique planifiée démocratiquement dans un esprit de justice sociale et dans le souci du bien-être » (Parrique, September 2022, p. 15). Looking at these definitions, degrowth envisions a decline in production and consumption while maintaining the wellbeing of the society. This is exactly why degrowth is often regarded as an inefficient measure, as it challenges the traditional view of GDP growth.

In this paper, we argue that EE policies should move away from the conception of wanting to increase economic growth, and start to embrace a degrowth perspective, based on less energy consumption and production. This is strictly linked to what has been recently defined as energy sufficiency (in French sobrieté energetique). Energy sufficiency refers to a way of living by limiting our demand for energy, materials and resources to the minimum needs (Parrique, Apri 24, 2022; ADEME, 2021). Energy sufficiency means degrowth (Parrique, Apri 24, 2022) and implies therefore a more sober approach to how we live and consume (NegaWattm, n.a.). Different scenarios such as the RTE, the ADEME and NegaWatt 2050 scenarios argue that in order to achieve climate neutrality we would need inevitably to consume less energy and become energy sufficient (Mayer and Guerineau, 2022). Moreover, what is interesting is that thanks to energy sufficiency it may be possible to reduce the impacts of the rebound effects by indeed limiting our energy consumption and make sure that cost savings from EE are spent on non-energy intensive goods and services (Darby & Fawcett, 2018).

The question that arises now is how the policy could successfully accompany such a move to energy sufficiency? We argue that policies should go beyond energy efficiency and encourage demand reductions. Energy efficiency is necessary, but it not enough to reach climate neutrality therefore it should be complemented by energy sufficiency through more radical changes in consumption patterns. Consumption reduction should be indeed the overall goal of public policy. What can policies do in practice? We believe for instance that an important policy measure to promote energy sufficiency is the decrease in working hours and the introduction a shorter working week of 3 or 4 days: in this way household consumption decreases as a result of working less and earning less and thus reduce their environmental impacts. This is linked to the concept of downshifting, that is the voluntary decrease of household income by deciding to work less or move to lower salary but more satisfying jobs (Darby & Fawcett, 2018). Emissions are strongly correlated with income levels, and it has been proven that by downshifting and working less, households could drastically reduce their emissions but also improve their quality of life as they have more free time from work (Sorrell, 2018). Some other practical policies to integrate energy sufficiency in everyday life include reduction in the thermostat temperature, decrease in individual travel and reduction in average travel speed and vehicle size (RTE, 2021). All the above-mentioned measures on one side imply to change completely the lifestyle and lower the level of comfort of citizens but on the other side they may help to reduce energy consumption and decrease the impacts of rebound effects (Darby & Fawcett, 2018).

To conclude, it is the role of policymakers to clarify what is the goal of policies, to increase economic growth in GDP terms or decrease emissions. This paper suggests that if the goal is to reach climate neutrality and reduce energy consumption, we cannot and we should not think anymore in GDP terms, but instead we should start introducing a degrowth approach in EE policy making and support energy sufficiency even if it implies a profound behavioural change and a disruptive reorganization of the society.

Bibliography

Ademe (2021). Transition(s) 2050. Choisir maintenant Agir pour le climat. https://librairie.ademe.fr/cadic/6529/transitions2050-synthese.pdf

Darby & Fawcett (2018). Energy sufficiency: an introduction. Concept paper. ECEE. https://www.energysufficiency.org/media/uploads/site-8/library/papers/sufficiency-introduction-final-oct2018.pdf

European Commission (2017). The macro-level and sectoral impacts of Energy Efficiency policies. Final report. https://energy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2017-07/the_macro-level_and_sectoral_impacts_of_energy_efficiency_policies_0.pdf

IEA (2014). Capturing the Multiple Benefits of Energy Efficiency. Paris. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/28f84ed8-4101-4e95-ae51-9536b6436f14/Multiple_Benefits_of_Energy_Efficiency-148×199.pdf

Keyßer, L.T., Lenzen, M. (2021). 1.5 °C degrowth scenarios suggest the need for new mitigation pathways. Nat Commun 12, 2676. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22884-9

Lange S., et al. (2021). The Jevons paradox unravelled: A multi-level typology of rebound effects and mechanisms. Energy Research & Social Science, 74. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221462962100075X

Mayer, J. and Guerineau, M. (2022). Reducing emissions: how to be more energy “sufficient”. Polytechnique insights. A review by Institut Polytechnique de Paris. https://www.polytechnique-insights.com/en/braincamps/economy/ideas-around-degrowth-is-gdp-on-its-way-out/reducing-emissions-how-to-be-more-energy-sufficient/

NegaWatt (n.a.). Energy sufficiency: towards a more sustainable and fair society. https://negawatt.org/energy-sufficiency

Parrique, T. (September, 2022). Ralentir ou Périr. L’économie de la décroissance. Paris : Editions du Seuil. Print.

Parrique, T. (April 24, 2022). Sufficiency means degrowth. https://timotheeparrique.com/sufficiency-means-degrowth/

RTE (2021). Energy Pathways to 2050. Key results. https://assets.rte-france.com/prod/public/2022-01/Energy%20pathways%202050_Key%20results.pdf

Sorrell, S. (2018). Energy sufficiency and rebound effects. Concept paper. ECEE. https://www.energysufficiency.org/media/uploads/site-8/library/papers/sufficiency-rebound-final_formatted_181118.pdf