Climate Unpacked: Episode 1

1 October 2023

Executive training for the African Carbon Markets Initiative

10 October 2023Since the 2010s, nature-based solutions (NBS) have been rising in the agendas of policymakers as tools to simultaneously advance economic, social and environmental goals in cities and beyond. This blog post examines what are the particularities and the challenges in financing NBS in Europe, from accounting and evaluation of projects to the choice between private vs public sources.

By Valeria de los Casares, Research Assistant for the European Chair for Sustainable Development and Climate Transition

____________________________________

Nature-based Solutions (NBS) are actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural and modified ecosystems that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously benefiting people and nature (IUCN 2023). They are rooted in the idea that ecosystems provide value to human life in different ways. This includes all the natural functions that make our life on earth possible, such as absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen or supplying us with food and clean water, but also by providing us with recreation spaces, increasing our well-being or by helping us adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change (such as by protecting us against flooding or extreme temperatures). In this sense, NBS are solutions, projects or interventions that can take place at the city level, but also in seascapes or landscapes, that aim to bring or enhance the benefits or ‘services’ that ecosystems bring to humans. More specifically, the European Commission defines NBS as:

“Solutions that are inspired and supported by nature, which are cost-effective, simultaneously provide environmental, social and economic benefits and help build resilience. Such solutions bring more, and more diverse, nature and natural features and processes into cities, landscapes and seascapes, through locally adapted, resource-efficient and systemic interventions.”

Moreover, ‘NBS’ is also commonly understood as an umbrella term for other ecosystem-based approaches, such as green and blue infrastructure or natural water retention measures (Escobedo et al., 2019). Over the past decade, the concept has been embraced by institutions such as the IUCN or the EU and has become a popular way to simultaneously refer to these approaches, as it is a more simple and less technical term than previous ones (EEA, 2021). In this sense, it has served to encompass a range of solutions and research streams that were previously reserved for expert communities and to diffuse this knowledge among the wider public and policymakers. By doing so, the NBS concept has contributed to the mainstreaming of ecosystem-based approaches to solve issues across different areas (ibid.). Nature-based solutions have, as such, emerged as a powerful approach to address environmental challenges while promoting sustainable development and resilience in Europe.

This post explores the various aspects of financing for nature-based solutions in Europe, looking at the sources of funding, financing instruments, and the role of the public and private sectors in driving NBS investment.

Who finances nature-based solutions?

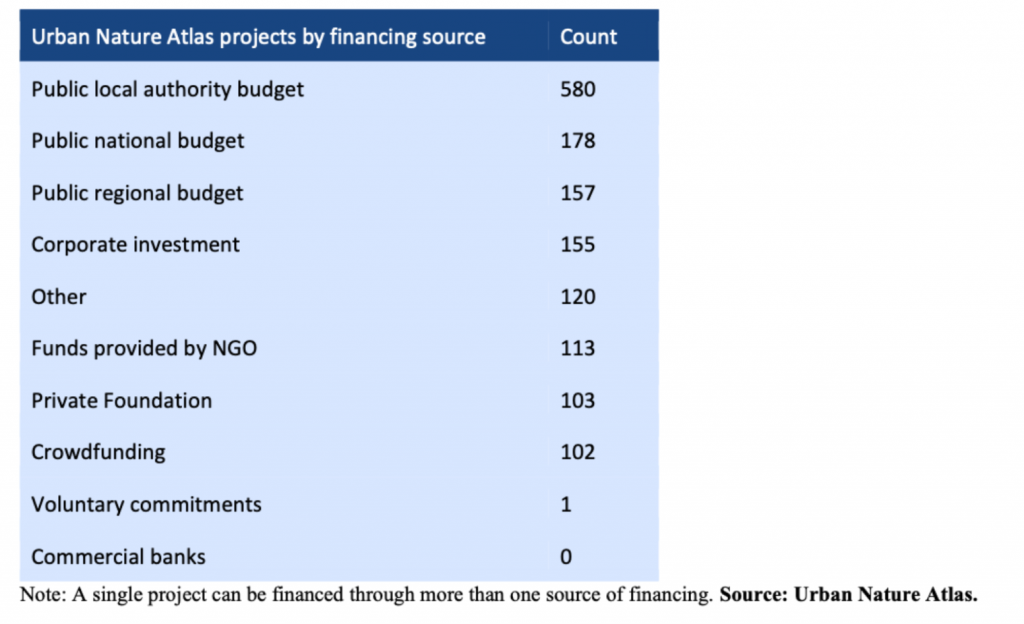

While numbers vary, sources estimate that around 75-91% of financing for nature-based solutions comes from public sources (EIB, 2023; UNEP, 2019; Urban Nature Atlas). This is because NBS are commonly regarded as public goods, due to the benefits they bring to communities and the fact that it is difficult for companies to make a profit from them. In particular, the use of grants and public budgets are commonly cited as the main instruments for funding nature-based solutions in the European Union (EIB, 2023). This includes money coming from local or regional budgets or grants, as well as money obtained through European funding instruments or European grants. The table below shows the number of projects, listed by financing source, that are compiled under the Urban Nature Atlas, the largest NBS database, containing 1003 case studies of urban NBS in Europe.

Table 1. Projects on the Urban Nature Atlas by sources of financing. From our Working Paper ‘Nature-based Solutions for Climate Adaptation in the European Union: Analysing Governance and Financing Barriers’ (2023).

We find that project characteristics, including goals or scale of the intervention, have an influence on the financing mix and institutions in charge of the project’s management. For example, while urban parks or gardens are commonly funded and managed by local public authorities, we can see (for example in the Urban Nature Atlas) that small green areas in buildings such as green roofs or walls are often found as part of larger grey or traditional commercial construction projects. These are more commonly implemented by private companies than other types of NBS and their commercialisation is more widely diffused, though with uneven progress, across countries in the EU. Their smaller scale compared to other NBS and quantifiable benefits in terms of water retention have also been more documented. On the other extreme, projects such as the re-naturalisation of a river basin or a reforestation initiative, usually fall under the scope of regional or local public authorities or a public-private partnerships, given that they require technical expertise and coordination to be managed, that the benefits they bring are more difficult to quantify and that these benefits also accrue for larger groups of stakeholders or communities.

Moreover, innovative financing instruments such as nature-based enterprises (see below for more information; Kooijman et al., 2021), green public procurement, green finance or other market-based instruments (such as tax rebates or user fees) are being increasingly studied and developed (Baroni et al., 2019). This trend is partly being driven by efforts in spreading visibility on the opportunities for doing business that involves nature. EU-funded projects such as ‘Connecting Nature’ work alongside local authorities, communities and industry partners that are investing in NBS implementation in cities. They measure impacts of these projects and also “nurture the start-up and growth of commercial and social enterprises active in producing nature-based solutions and products”. Some of the progress with advancing the perception of the economic role that NBS can have in the economy is reflected across EU reports such as ‘The vital role of nature-based solutions in a nature positive economy’ (2022) or ‘Public procurement of nature-based solutions’ (2020).

While it is recognised that public financing alone is insufficient to fund all the required investments to restore and protect nature and biodiversity (Kooijman et al., 2021), some authors have warned against the challenges associated with developing private financing for NBS (Chausson et al., 2023). In their study, Chausson and colleagues (2023) point at governance issues and potential risk of greenwashing as potential pitfalls for promoting private finance for nature-based solutions.

What is the current state of financing for NBS?

The lack of data on the financing for NBS makes it difficult to get an estimation of the current level of investment in nature-based solutions. Available studies often rely on databases of under 1000 projects that have been manually identified based on a number of keywords (i.e., EIB (2023) that use databases such as the Urban Nature Atlas, Oppla, Biodiversa or NWRM Platform). Moreover, gathering data on the financial scale of NBS projects poses challenges given the diverse range of projects and the relative novelty of the concept, which was introduced into mainstream policy debate around 2012. This implies that earlier projects might employ different terminology to refer to interventions that are now understood or classified as nature-based solutions. Thus, biases in selection of case studies as well as small sample sizes might result in inaccurate or mixed results depending on the keywords employed, or even on the visibility that different NBS projects have (e.g., being included in certain databases as a result of having received funds from a given EU project).

This considered, private investors are gaining interest in NBS and businesses that are looking to incorporate nature into their activities are growing (EIB, 2023). We see different ways in which companies can work with the NBS concept, such as by investing in these solutions through an ‘altruistic’ approach and accepting lower or no rates of return; or by incorporating NBS into one or more of their services and offering it as a ‘premium’ or ‘innovative’ service. In the first case, these investments can be carried out by an independent private foundation, looking to create a positive impact in a community, or by a business looking to invest in green solutions and to reduce its net carbon impact. In the second case, while still only applicable to a small number of cases, companies are seeking to incorporate nature into their activities in order to increase their sustainability, but also as a way of innovating their products and/or services. In this respect, the concept of ‘nature-based enterprises’ (NBEs) has emerged in recent years to denote “‘an enterprise, engaged in economic activity, that uses nature sustainably as a core element of their product/service offering” (Kooijman et al., 2021). The Horizon 2020 project ‘Connecting Nature’ has developed this concept and studied the different activities that NBEs tend to carry out. Nonetheless, while interest in this type of NBS projects is growing, we still see mostly small-scale initiatives and limited success cases. An interesting case of companies working with nature is that of insurance firms using NBS or nature-based infrastructure. There have been a number of companies announcing pledges to invest in this area. While company announcements and policy articles inform about this topic, academic literature on the case is still scarce.

Last, the European Union is also a considerable funder of NBS in Europe. In fact, studies estimate that the EU has dedicated more than 240 million EUR to NBS research projects (data updated as of 2019) (Cohen-Shacham et al., 2019). Moreover, the Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 pledged that 30% of dedicated funds to climate action is invested in biodiversity and nature-based solutions.

What are the challenges for financing nature-based solutions ?

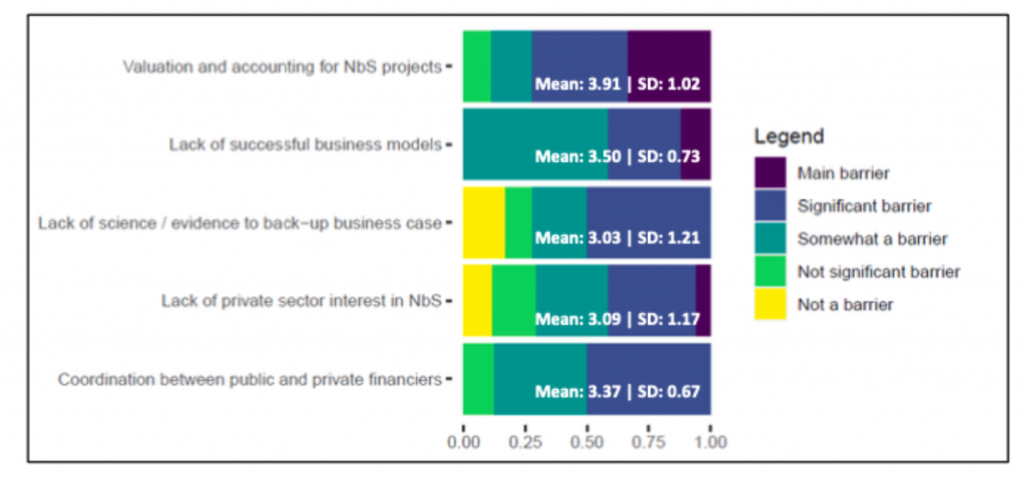

Developing financial instruments and upscaling nature-based solutions in Europe are often hindered by difficulties in measuring benefits and impacts of projects, loose definitions or standards or simply lack of compatibility with investor needs. As part of our working paper on the barriers to implementing NBS, we conducted interviews with experts and asked them to rate a series of barriers regarding their significance for hindering NBS diffusion. Figure 1 shows the responses of these experts regarding barriers to financing NBS. Experts attributed more significance to barriers such as the ‘valuation and accounting’ and the ‘lack of successful business models’ for NBS projects. In contrast, they found the ‘lack of science or evidence to back-up the business case’ or ‘lack of coordination between public and private financiers’ to be less of a barrier.

Figure 1. Distribution of respondent’ assessments on financing barriers for NBS. From our Working Paper ‘Nature-based Solutions for Climate Adaptation in the European Union: Analysing Governance and Financing Barriers’ (2023).

In fact, several experts argued that science or evidence on NBS benefits has developed rapidly in recent years, but instead found that the problem was more often that the communication of this evidence was not so advanced or that it hadn’t reached yet some groups of stakeholders. Moreover, how to quantify these benefits or even compare them across projects presented an added challenge. In this respect, experts raised the limited comparability, replicability and scalability of projects as prevailing barriers.

A big piece of the puzzle and related challenge is the lack of integrated approaches to govern NBS. This essentially means that nature-based solutions are often implemented by actors working in one area of government (such as urban or landscape planning) and the management and governance of the project tends to be reserved to those actors. Moreover, projects are not developed in a bigger regional or national lens or coordinated with other departments that might also see their objectives advance with the implementation of NBS (health, mobility…). In this light, some EU-funded Horizon 2020 and LIFE projects are addressing this aspect and have tested collaborative arrangements across cities in order to study and replicate NBS.

As NBS gains recognition, the private sector is increasingly showing interest in these projects. As mentioned, research on nature-based enterprises that combine profitability with environmental and social goals, is on the rise. Private investment in NBS projects is growing, albeit more in smaller-scale initiatives. The issues cited amongst private sector actors during interviews were mainly three: Firstly, the need to develop harmonised evaluation and accounting frameworks and standards to increase comparability among projects as well as to avoid greenwashing. Secondly, actors cited the NBS projects’ lack of compatibility with investor needs in terms of investment sizes. Finally, respondents highlighted the difficulty in changing ‘old patterns’ in areas such as infrastructure or construction and pointed to the role of incentives, information sharing and to local governments in changing these patterns, as well as to the importance of having ‘solid’ evidence on the benefits of nature-based projects compared to grey projects.

Conclusion

While financing for nature-based solutions in Europe is currently dominated by public grants and public local budgets, private actors are increasingly gaining interest and innovative financing instruments are emerging. Nonetheless, barriers exist for both public and private finance. To address these, we must acknowledge that challenges associated with knowledge diffusion or governance of NBS play an important role as well in the mainstreaming of this approach. As such, when we look at the barriers to financing, such as lack of harmonised evaluation methods or issues of replicability and scalability, we need to look at transversal barriers, like the lack of integrated approaches or existing silos. By doing so, we can understand better what is hindering adoption of NBS and adopt collaborative methods to solve these challenges. EU-funded projects are already doing some of this but a larger effort and change in the approach that we have to look at investments in nature needs to be done.

Our analysis can be summarised in four main findings:

1. Financing of NBS remains mostly reliant on public budgets and public grants. EU grants are particularly widespread in Europe.

2. There have been efforts to boost private investment on NBS (such as the development of nature-based enterprises), but we have not observed a substantial change of paradigm as NBS is still typically regarded as a type of public good.

3. Private sector has interest in investing in NBS but mismatches in terms of project size or lack of evaluation methods and information limit its involvement.

4. ROI and business models have not yet been fully developed for NBS, but initiatives are on the rise.

Further to these, we stress the importance of communication and knowledge sharing, particularly in this emerging field, and leave below some resources for those interested in understanding more on financing NBS. To read our full analysis that derives further lessons and develops policy recommendations based on our findings, please access our Working Papers here.

Some resources*

*This list is non-exhaustive and constitutes just a collection of websites, reports or articles on NBS financing that were found in the process of writing this article.

1. Report ‘Catalysing Finance and Insurance for Nature-based Solutions’ by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, 2023. Available: https://www.greenfinanceplatform.org/case-studies/catalysing-finance-and-insurance-nature-based-solutions

Description: This report presents a variety of cases in which the private financial sector is supporting nature-based solutions in emerging markets and developing countries. These include investment projects, funds and insurance vehicles across a variety of ecosystems, including mangroves, coral reefs and agricultural systems.

2. ConnectingNature article on Financing and Business models for nature-based solutions. Available:https://connectingnature.eu/financing-and-business-models

3. Recommendations from the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures

Available: https://tnfd.global/recommendations-of-the-tnfd/#overview

Description: The TNFD disclosure framework consists of conceptual foundations for nature-related disclosures, a set of general requirements, a set of recommended disclosures structured around the four recommendation pillars of governance, strategy, risk and impact management, and metrics and targets.

4. Report by the WWF ‘Nature in Transition Plans’ (2023).

Available at: https://www.wwf.org.uk/our-reports/wwf-nature-transition-plans

Description: A critical opportunity to bring the solutions to climate change and nature loss together is in transition planning. To date, the focus of transition plans has largely been on climate change – where businesses and financial institutions demonstrate how they will manage climate risks and take action to reach their climate targets. This report proposes that businesses take a stepwise approach to integrating nature in existing transition planning frameworks and explores actions to do so.

5. Information on Paris’ new urbanism plan: towards a greener and more solidary Paris.

Available (in French): https://www.paris.fr/pages/plan-local-d-urbanisme-bioclimatique-vers-un-paris-plus-vert-et-plus-solidaire-23805

References

Anguelovski, I., Connolly, J. J. T., Pearsall, H., Shokry, G., Checker, M., Maantay, J., Gould, K., Lewis, T., Maroko, A., & RoberWV, J. T. (2019). Why green climate gentrification ́ threatens poor and vulnerable populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(52), 26139-26143. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1920490117

Baroni, L., Nicholls, G. & Whiteoak, K. (2019). Approaches to financing nature-based solutions in cities. Working Document, Grow Green Project. Available at: http://growgreenproject.eu/wp- content/uploads/2019/03/Working-Document_Financing-NBS-in-cities.pdf

Calliari, E., Castellari, S., Davis, M., Linnerooth-Bayer, J., Martin, J., Mysiak, J., Pastor, T., Ramieri, E., Scolobig, A., Sterk, M., Veerkamp, C., Wendling, L., & Zandersen, M. (2022). Building climate resilience through nature-based solutions in Europe: A review of enabling knowledge, finance and governance frameworks. Climate Risk Management, 37, 100450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2022.100450

Chausson, A., Welden, E. A., Melanidis, M. S., Gray, E., Hirons, M., & Seddon, N. (2023). Going beyond market-based mechanisms to finance nature-based solutions and foster sustainable futures. PLOS Climate, 2(4), e0000169. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000169

Cohen-Shacham, E., Andrade, A., Dalton, J., Dudley, N., Jones, M., Kumar, C., … & Walters, G. (2019). Core principles for successfully implementing and upscaling Nature-based Solutions. Environmental Science & Policy, 98, 20-29.

Egusquiza, A., Arana-Bollar, M., Sopelana, A., & Babí Almenar, J. (2021). Conceptual and Operational Integration of Governance, Financing, and Business Models for Urban Nature-Based Solutions. Sustainability, 13(21), 11931. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111931

Escobedo, F. J., Giannico, V., Jim, C. Y., Sanesi, G., & Lafortezza, R. (2019). Urban forests, ecosystem services, green infrastructure and nature-based solutions: Nexus or evolving metaphors?. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 37, 3-12.

European Commission. (2022). Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Nature Restoration, 22 June 2022, COM(2022) 304 final, available at: https://eur- lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022PC0304 [accessed 25 July 2023]

European Commission. Directorate General for Research and Innovation (2020c). Public procurement of nature-based solutions: addressing barriers to the procurement of urban NBS : case studies and recommendations. Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/561021

European Commission. Directorate General for Research and Innovation (2015). Towards an EU research and innovation policy agenda for nature-based solutions and re-naturing cities: final report of the Horizon 2020 expert group on ’Nature based solutions and re naturing cities’. Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/479582

European Environment Agency. (2021). Nature-based solutions in Europe policy, knowledge and practice for climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2800/919315

IUCN. (2020). Guidance for using the IUCN global standard for nature-based solutions (1st ed.).

Kabisch, N., Frantzeskaki, N., Pauleit, S., Naumann, S., Davis, M., Artmann, M., Haase, D., Knapp, S., Korn, H., Stadler, J., Zaunberger, K., & Bonn, A. (2016). Nature-based solutions to climate change mitigation and adaptation in urban areas: perspectives on indicators, knowledge gaps, barriers, and opportunities for action. Ecology and Society, 21(2). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26270403

Kooijman, E. D., McQuaid, S., Rhodes, M. L., Collier, M. J., & Pilla, F. (2021). Innovating with nature: From nature-based solutions to nature-based enterprises. Sustainability, 13(3), 1263.

Raymond, C. M., Frantzeskaki, N., Kabisch, N., Berry, P., Breil, M., Nita, M. R., Geneletti, D., & Calfapietra, C. (2017). A framework for assessing and implementing the co-benefits of nature-based solutions in urban areas. Environmental Science & Policy, 77, 15- 24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.07.008

Toxopeus, H., & Polzin, F. (2021). Reviewing financing barriers and strategies for urban nature-based solutions. Journal of Environmental Management, 289, 112371.

Zandersen, M., Oddershede, J. S., Pedersen, A. B., Nielsen, H. Ø., & Termansen, M. (2021). Nature based solutions for climate adaptation-paying farmers for flood control. Ecological Economics, 179, 106705.