Event Summary: Global Climate Perspectives Ahead of COP29: Insights from the EIB Climate Survey and Key Lessons for the EU

13 November 2024

Call for Submissions to the Sciences Po Energy Review

5 December 2024It’s COP time again. For the 29th time, Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (or UNFCCC) are meeting to discuss how to reach the Convention’s ultimate objective of preventing “dangerous” interference with the climate system. While not quite as big as the record-breaking COP28 in Dubai last year, which attracted around 100,000 attendees from around the world, COP29 is still a mega-event, with an estimated 30 to 40,000 participants.

DAY 1, 11 November 2024. Getting started

From Carola Klöck

Among them is also our small team. We are at COP29 with our project “Beyond Coalitions – Small States in Climate Negotiations” (or BeCoSS Climate, in short). The project is a collaboration between Sciences Po and ZHAW (Zurich University of Applied Sciences). It sheds light on states like Andorra, Iceland, Fiji or Suriname. Countries that are rarely in the limelight of international politics but that actually make up the majority of the UNFCCC’s 197 Parties (196 states and the European Union). While de jure equal, these states have not the same means, resources and opportunities as their larger counterparts. At the same time, they depend on these climate meetings and decisions, even more so than larger states, given that most small states are minute emitters of greenhouse gases, but are sometimes extremely vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change.

How then do these countries deal with these asymmetries? To what extent are small states present, how do they participate in the discussions, and when do they manage to make themselves heard? These are the questions that are at the core of our 4-year project, and direct observation of the negotiations are key to addressing them.

Just like many small states, we have only limited means, and therefore have to pick and choose the negotiations we want to follow, the side and pavilion events we want to attend.

We (Carola Klöck, Sarah Tegas and Sarah Thompson) will share some of our impressions, experiences and learnings here—and invite you to follow over the next two weeks!

DAY 2, 12 November 2024. The Finance COP – Negotiating the New Collective Quantifiable Goal (NCQG) on climate finance

From Sarah Tegas

For the past three years, climate negotiators have been deliberating on the elaboration of a new finance target, from a floor of a 100 billion USD per year as agreed on COP21 in 2015, which led to the Paris Agreement. Hence called the finance COP, this 29th edition aims to conclude these deliberations and unlock the finance needed to fund climate action (mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage) in developing countries.

On November 12, the negotiations started with a “Contact Group” meeting where parties expressed their views and concerns toward the report made by the co-chairs of NCQG work programme. Many states intervened in this meeting, extending it by more than an hour. For instance, various developing states echoed the words of the G77+China coalition group in calling out the need to extend the finance goal to more than 1 trillion USD to match the necessary climate action and respond to the many already-unfolding climate disasters. The co-chairs took into consideration all these interventions before deciding on how to proceed further with the negotiations.

Due to in-room limited capacities, observers were given access to a side-room to follow the negotiations.

DAY 3, 13 November 2024. Unlocking Climate Finance?

From Sarah Tegas

Continuing on the finance topic, Wednesday 13 November started for us with an online side-event organised by Island Innovation on climate finance and resilience in the Pacific Small Island Developing States (SIDS). The session discussed how the decisions being made at COP29 might affect the Pacific, and what are some of the solutions already being developed and implemented across the region.

Unlocking Climate Finance, Side Event. COP 29 in Baku, 13 November 2024

As the negotiations are only getting started on the topic, it will be interesting to follow closely how SIDS’ positioning will be incorporated into the final agreement.

They stand for prioritising grant-based and highly concessional public finance. They deem the issue of the contributor base highly contentious, as its definition will imply whose status might turn to contributor to climate finance across time and economic developing stages.

Additionally, the Standing Committee on Finance of the UNFCCC presented the key findings of its reports. Amongst its speakers was Kevin Adams, lead negotiator on climate finance for the Biden Administration. He discussed the distribution of needs in terms of climate finance across developing countries. A key finding expressed was that most costed needs are reported in Asia, while the highest number of expressed needs are reported in Africa.

From Sarah Thompson

I spent the day observing “contact group” meetings focused on a range of finance topics. These informal working groups dive into technical aspects of proposed frameworks, facing fewer procedural constraints than the plenary sessions. Climate negotiators in these groups, representing various countries or coalitions, have been working collaboratively, providing feedback on specific reports on topics including the Green Climate Fund, the Global Environment Facility, the Adaptation Fund, and Loss and Damage, among others. Some of the most common points raised today were requests to: streamline guidance and processes, ensure greater access to support for developing countries (including least developed countries – LDCs – and small island developing states – SIDS), and improve gender and indigenous inclusion in governance and programming.

Observers following finance negotiations – Contact Group: New collective quantified goal on climate finance – CMA 11 (a), COP 29 Baku, 13 November

Guidance on the forthcoming Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage received widespread support from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the EU, the Africa Group, the Independent Alliance of Latin America and the Caribbean, the Alliance of Small Island States, and the Least Developed Countries (LDCs). Key milestones were celebrated, including the selection of the Philippines as the host country and the appointment of the fund’s executive director, with many calling for the fund’s swift operationalisation.

Finally, an informal discussion was held toward the end of the day on the highly-anticipated new collective quantified goal (NCQG) for climate finance, with a strong call across countries and coalitions—including G77+China, the UK, Canada, Norway, the Arab Group, and the Environmental Integrity Group—to further refine the text of the goal’s framework and narrow in on the technical and substantive content. Another draft is therefore in progress, and they have been given the rapidly approaching deadline of Saturday, 16 November to finalise their work on the framework for the NCQG.

DAY 4, 14 November 2024. Unlocking Climate Finance?

From Sarah Tegas

This morning Sarah Tegas followed the 6th High-Level Ministerial Dialogue on Climate Finance. The COP29 president, Mr. Mukhtar Babayev, made an intervention calling out for the urgency of mobilising climate finance, given the scale and scope of climate disasters already unfolding.

He argued for a common goal in the trillions, composed of public finance in the hundreds of billions.

Various ministers and negotiators took the floor to express their views on the lessons learned from the delivery of the previous climate finance goal – the US$100billion, what good practices could be maintained and which ones to improve. A rather clear divide between developing and developed countries was observed in their responses to the latter. Some called out the US$100billion goal’s lack of transparency and reliance on debt-based instruments, while others applauded how the goal was exceeded and how they contributed to it. Members of the Standing Committee on Finance presented some highlights of a recent report on progress towards meeting the goal, indicating that while the OECD (and many of its member countries) claim it was met and surpassed in 2022, Oxfam has conversely asserted that the OECD figures overstate the true value of climate finance by a significant margin.

From Sarah Thompson

In line with the ongoing theme of finance, I attended the event ‘Integrating climate action into development finance’ co-organised with the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). To set the stage, Carsten Staur—Chair of the Development Assistance Committee at the OECD—provided some key trends signalling that climate is moving to the the centre of the international cooperation agenda:

- The overall share of climate-related development assistance focused on adaptation has increased;

- Climate action is being mainstreamed within different areas of development cooperation ; and

- Integrating climate action into development finance has not decreased the overall amount of development assistance targeting least developed countries (LDCs).

A number of countries later took turns intervening, with many developed countries remarking on the contributions they have previously and are committed to making moving forward, while developing countries highlighted their increasingly urgent needs for more and ‘better’ finance (in particular, grants rather than loans). Overall, there was a broad consensus—echoing previous meetings—that more finance is needed and that a greater diversity of sources (e.g., increasing the base of donor countries) and types (e.g., public, private, blended) should be mobilised, key elements that will soon become clear when the formulation of the new collective quantified goal (NCQG) is announced.

The French representative, Rémy Rioux, speaking during the event ‘Integrating climate action into development finance’, COP 29, 14 November 2024

DAY 5, 15 November 2024. Myths, and reality

From Sarah Thompson

The panel of speakers during the event ‘Why do we need public finance at the heart of the new finance goal?’ COP 29, 15 November 2024

Keeping again with the theme of climate finance, I attended the side event ‘Why do we need public finance at the heart of the new finance goal?’ with speakers from Climate Action International, Action Aid International Foundation, the Center for Economic and Social Rights, Christian Aid, and Fossil Treaty. The conversation kicked off with an overview of the current state of play of the ongoing NCQG negotiations, highlighting that the next Ministerial Dialogue should begin negotiations next week on the framework that is still being worked on by the contact group. Speakers then explored the critical role of public finance in ensuring a fair and equitable transition by debunking a series of myths surrounding climate finance, including:

- The myth that developed countries have already met the US$100 billion goal, which has since been revealed to be a substantial overstatement once adjusted for loans and funds that do not meet the criteria of being ‘new and additional’.

- The myth that loans can serve as effective climate finance, where it was noted that 97% of climate vulnerable countries are already at risk of debt distress. Speakers argued that loans push vulnerable nations further into debt with debt servicing costs often 4 times higher than those paid by developed countries, which ultimately undermines their ability to adapt to or mitigate climate impacts, let alone address loss and damage.

- The myth that private sector investment can substitute public finance, where speakers explained how reliance on private finance mechanisms, such as de-risking loans and insurance schemes, often prioritises profit over justice and fails to address the urgent needs of vulnerable communities, especially for adaptation and loss and damage.

- The myth that there is not enough public money available, countered by examples like the trillions spent annually on fossil fuel subsidies and military budgets, and soaring corporate profits, which could be redirected to climate action under fairer global tax frameworks.

- The myth that all countries should equally contribute to climate finance was challenged by the speakers given the historical responsibility of developed nations for the climate crisis. Speakers emphasised the need for developed countries to fulfil their commitments before shifting the burden to emerging economies (as is often pushed for by developed countries), ensuring justice and equity remain at the core of negotiations.

The discussion made clear that without public, grant-based finance at the core, the NCQG risks reinforcing existing inequalities and pushing developing countries further into debt crises, rather than addressing the systemic injustice driving the climate crisis.

The satirical ‘Fossil of the Day’ award being presented to the G7 countries for their efforts in hindering meaningful progress during the negotiations, COP 29, 15 November 2024

Following this event, the Climate Action Network (CAN) then awarded the ‘Fossil of the Day’ award to the G7 countries—United States, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom. This satirical award is presented to countries that are deemed to have made the least constructive contributions and hindered progress during climate change negotiations. As CAN announced, the G7 was awarded the first Fossil of the Day “for spending the past 20 years dodging, skirting, and running away from their fiscal responsibility to pay up for their growing climate finance debt.”

DAY 6, 16 November 2024. Balancing the quality and quantity of climate finance

From Sarah Thompson

The panel of speakers during the event ‘Unveiling the Money Trail: Climate Finance Accountability through Local Tracking and Validation’

Rounding out the first week, I attended two more side events focused on climate finance. The first event, titled ‘Unveiling the Money Trail: Climate Finance Accountability through Local Tracking and Validation,’ explored the importance of tracking climate finance flows from donor countries to recipient communities. Speakers highlighted significant gaps that often exist between climate finance commitments and the actual amounts distributed and, echoing earlier presentations, they emphasised the need to focus not just on the quantity of climate finance but also on its quality.

Representatives from the African Climate Reality Project presented findings from a case study in South Africa. They noted that Official Development Assistance (ODA) loans made up a large majority (75%) of climate finance allocated specifically for adaptation. They pointed out the challenges posed by this arrangement, as these loans must be repaid in foreign currencies, further exacerbating the debt burden for a country with a weaker local currency. Interestingly, they also highlighted discrepancies in climate finance targeted towards mitigation. While a significant portion (nearly half) of committed funds was initially earmarked for non-renewable sectors, the actual disbursements favoured renewable sectors (approximately 32%). This shift likely reflected the influence of landmark environmental agreements made between the commitment and disbursement phases. However, it was also noted that the overall amounts of climate finance for mitigation ultimately disbursed fell significantly short of the commitments, whereas the amounts committed for adaptation were similar to actual amounts disbursed.

The panel of speakers during the event ‘The role of the NCQG in achieving a just transition in the Global South: What can MDBs do?

The second event I attended was hosted by Recourse, Germanwatch, and GFLAC, titled ‘The role of the NCQG in achieving a just transition in the Global South: What can MDBs do?’ It focused on the expectations and concerns of climate finance and the role of multilateral development banks (MDBs) in delivering the COP28 energy package and NDCs, Paris Alignment and how countries and communities in the global south can maximise national and local benefits of just energy transition.

Featuring several speakers coming from NGOs and one speaker from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the event highlighted slightly diverging perspectives. Those from NGOs highlighted the inadequacy of the US$100 billion climate finance target, emphasising that developing countries require trillions for meaningful action under the upcoming NCQG. As highlighted in previous events, they criticised the heavy reliance on loans rather than grants, which exacerbates debt stress in developing countries. Speakers stressed the importance of community-focused approaches, public financing for capacity building, and equitable energy transitions. Moreover, they remarked on the lack of investment in renewables in developing countries: the European Investment Bank, for example, was responsible for 46% of investment in renewable energy in 2022, however only 4% of their investments are outside of the EU. The emphasis was on ensuring that future MDB funding aligns with social, environmental, and local priorities, avoiding “green colonialism” and prioritising people over profits.

Germanwatch proposals on how MDBs can contribute to climate finance during the event ‘The role of the NCQG in achieving a just transition in the Global South: What can MDBs do?’

Avinash Persaud from the Inter-American Development Bank highlighted the critical role of MDBs in addressing the substantial financing gap for climate finance needs. While emphasising that these institutions are banks, not grant providers, he noted that the interest they earn on loans is then reinvested; in his words, MDBs have the most ‘stretchable dollar’, as $1 of capital invested in in MDBs can leverage $8 in lending, offering the opportunity to expand their resources and therefore their reach.

According to Persaud, by leveraging their AA credit ratings, MDBs could offer long-term, low-cost loans for projects like renewable energy, which generate revenue and savings, while leaving grant funding for urgent adaptation and loss and damage needs that private capital cannot address. This balanced approach could enable MDBs to make significant contributions to a new climate finance framework, providing $250–300 billion annually—double their current efforts—as a key contribution toward the NCQG, thereby arguing an expanded role for MDBs is the only way for an ambitious outcome on the goal.

However, Persaud noted that achieving these goals requires shifting the political and financial landscape, particularly in developed countries, where many recent elections have resulted in shifts to the far right, with mandates focused on reducing aid budgets rather than expanding them. Ultimately, he argued that MDBs must expand their role, private sector involvement must be optimised, and given the scarcity of grants, they must be reserved for the most critical needs of vulnerable countries.

DAY 8, 18 November 2024. Time to move forward

From Sarah Thompson

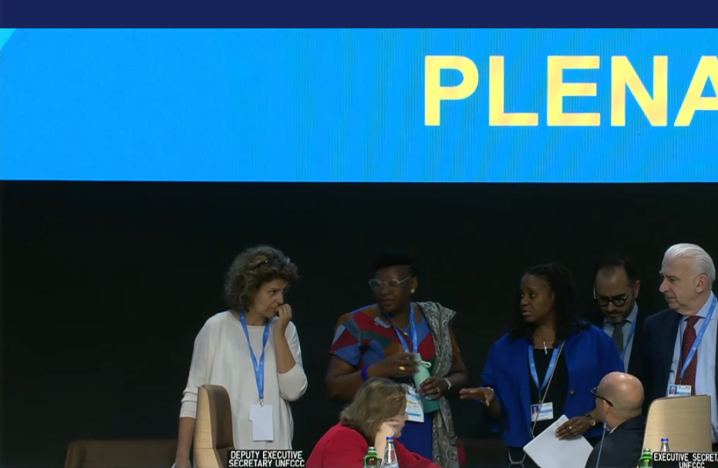

UNFCCC Executive Secretary, Simon Stiell, speaking at the Plenary on November 18

Today’s plenary, opened by COP President HE Mukhtar Babayev, outlined the work plan for the second week, with a focus on progressing negotiations. As I am closely following progress on the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG), key updates included the announcement that ministers from Egypt and Australia will lead consultations on the structure, quantum, and contributor base for the goal, with support from Brazil and the UK. While the draft text has been reduced to 25 pages, it still seems to be considered too lengthy and is under revision, with a new version expected by Tuesday, for discussion by the Ministers.

Statements were heard from various delegations and negotiating groups, reiterating their positions. UNFCCC Executive Secretary Simon Stiell also took the floor, urging delegates to resolve less contentious issues as early as possible so there is sufficient time for major political decisions. He cautioned against delays caused by ‘bluffing, brinkmanship, and premeditated playbooks’, and emphasised the need for collective progress to achieve an ambitious outcome. As he put it: “We can’t lose sight of the forest because we’re tussling over individual trees. Nor can we afford an outbreak of you-first-ism, where groups of parties dig in and refuse to move on one issue until others move elsewhere. This is a recipe for going literally nowhere and could set global climate efforts back at a time when we simply must be moving forward.”

DAY 9, 19 November 2024. Ministers have arrived

From Carola Klöck

We’re in the second week of the COP. Ministers have arrived and discussions on the thorniest issues that could not be resolved at the so-called “technical” level last week have now moved to the “political” level. These high-level negotiations tend to take place behind closed doors, leaving observers like us in the dark or dependent on rumours in the corridors.

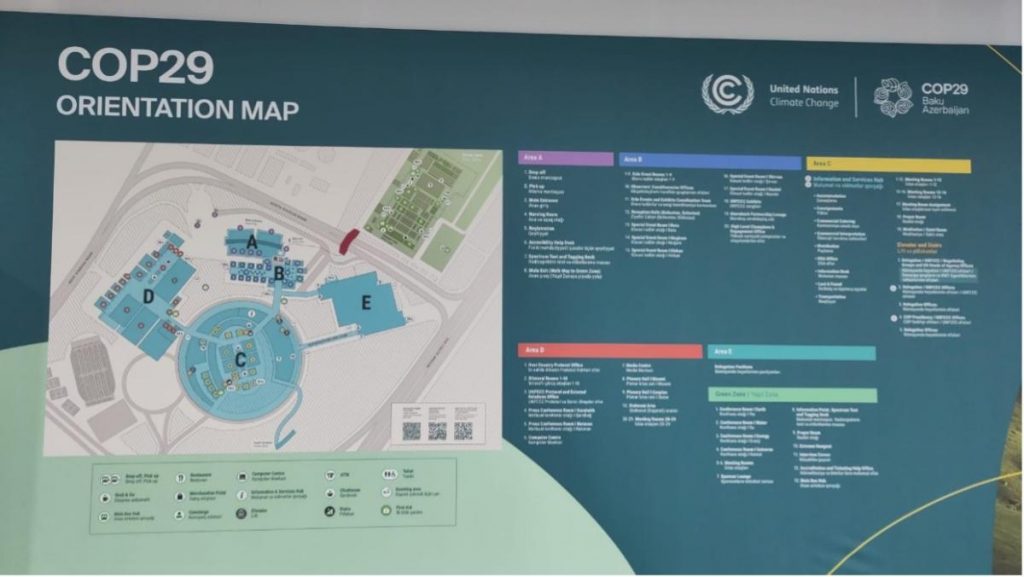

These different levels of negotiations show again just how complex and multi-layered these COPs are. We have already talked about the different spaces at the venue: the Green Zone, the Blue Zone, the pavilions, side events, and actual negotiation rooms, plus delegation offices, bilateral meeting rooms, or space for the media. Actually, we spend considerable amounts of time walking from one end of the venue to another, and back. Small states – at the centre of our research project – may not even be able to visit and cover these different spaces. I have heard from negotiators that they have not yet been to the pavilion area at all, let alone the Green Zone (which is across the street and requires going through security controls). Others, in contrast, may only have visited the pavilion area. Many delegations indeed have separate teams for separate objectives: a team to look after the pavilions or to speak at side events, and a team for the actual negotiations. Larger delegations here clearly are at an advantage, while smaller delegations have to choose where to go and what to attend.

Carbon Brief has analysed the provisional list of participants to find out which countries actually sent the largest delegations. Despite expectations that this COP would be much smaller than the record-breaking Dubai COP from last year, it seems that Baku actually ends up being the second-largest COP ever, just behind the Dubai COP. Unsurprisingly, the host country’s delegation is by far the largest one, with over 2,000 people in total. This is in stark contrast to previous COPs, where Azerbaijan had actually very small delegations of only 5 to 11 people (for the COPs between 2016 and 2022). France shows the opposite trend: the French delegation is much smaller this year than in previous COPs, given political tensions with the host countries. Political tensions also explain why Armenia has not sent even one delegate. Argentina has had a small delegation but ordered all delegates back last week Wednesday, while Papua New Guinea has already announced in August that it would “boycott” the negotiations given the disappointing results. In fact, Papua New Guinea has a (relatively small) delegation but decided not to send a minister.

Our project wants to examine such dynamics more closely, and explore presence in more detail. We argue that presence is a precondition for engagement, which in turn is a precondition for influence. We therefore want to understand who is present – as well as who is absent – but also who the delegates on the ground, e.g. whether countries send ministers or not. Such information is key to understanding negotiation dynamics, and although presence is such a fundamental aspect of negotiations, it has been surprisingly little studied in international relations and negotiation research.

From Sarah Tegas

EU Commissioner for Climate Action during the EU press conference on Monday 18 November

Since most negotiations at this time of COP are happening being closed-doors, as mentioned by Carola, I have turned my focus to press conferences and media reports to get some insights on the recent developments.

“We are very far apart as negotiators”, confirmed Woepka Hoekstra, EU Commissioner for climate action, during the European Union press conference on Monday 18 November. COP happening against the backdrop of a tumultuous geopolitical context, makes negotiations highly political—background noise, as the Commissioner mentioned, while negotiators should get their hands on the technicalities of the issues at stake that still haven’t been resolved.

On the NCQG negotiations, the most contentious issue concerns the determination of the contributor base. Who should pay? AOSIS’ lead finance negotiator, Michai Robertson, was unequivocal about having solely Annex I parties (so-called developed countries) as contributors, while the EU and the US are seeking to have emergent economies on board too (such as China). When asked about considering voluntary contributions to the NCQG from developing countries by a journalist from Carbon Brief, M. Hoekstra answered that “moving to a space with voluntary contributions is helpful and we would welcome countries making such a step”.

As the G20 take places in Rio de Janeiro, parallel to COP, many were expecting a statement from the group that would help unleash some of the tensions on climate finance. While the contributor base remains unresolved, the quantum that would define the new climate finance goal seems to be scaling from billions to trillions, but with no publicly disclosed figure yet.

The clock is ticking and the world awaits for collaborative efforts to be made to deliver in Baku, but much still remains to be determined at this point.

DAY 10, 20 November 2024. Voicing redlines

From Sarah Tegas

Redlines continue to be voiced by Parties on the NCQG. This time it is the Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDCs), the G77 and China, and the African Group of Negotiators (AGN) that held a press conference on Wednesday 20 November.

Island, Ocean and Climate. The Role of Sub-national Jurisdictions at COP 29. Baku, 20 November 2024

“Is it a joke?” replied Diego Pacheco (Bolivia, on behalf of LMDCs), and repeated Adonia Ayebare (Uganda, on behalf of G77), when asked how they would respond to a NCQG in the range of US$200 billion. Echoed by Ali Mohamed (Kenya, on behalf of AGN), the three negotiators expressed their concerns regarding the commitments from developed countries towards a new quantum for climate finance. They mentioned that the gap needed for adaptation finance has been estimated by up to 400 billion, making the total NCQG acceptable only in the trillions, based (amongst others) on calculations by the Standing Committee on Climate Finance of the UNFCCC. Likewise, Bolivia (on behalf of LMDCs) mentioned its “super red line” being not to reinterpret nor rewrite the Paris Agreement and its convention with regards to how Parties are classified between developed and developing status (Annex I vs non-Annex I). This recalls the debates on the contributor base of the NCQG, still ongoing in the negotiations.

Discussions about the draft text proposed by the co-chairs of the contact group on the Periodic review of the long-term global goal under the Convention and of overall progress towards achieving it. COP 29, Baku 20 November

Press conferences are key for the BeCoSS research project as they shed light on active participation by certain parties and how by speaking to the press they seek to spread their positioning and spur influence on the process and outcomes of the negotiations.

On a more positive note, the day ended with Parties approving the draft text proposed by the co-chairs of the contact group for CMA sub-item 11e Report of the Fund for responding to Loss and Damage and guidance to the Fund.

DAY 12, 22 November 2024. The last day—or not?

From Carola Klöck

This is our last day at the COP—we will be travelling back home tomorrow, Saturday 23 November. Many people seem to have left already. The venue is very quiet this morning, and the schedule is very empty, in stark contrast to the extremely busy last few days. The presidency released a first version of the final text early morning yesterday, and convened a plenary session at noon. This meeting, which went on for hours, gave Parties and groups a chance to react to these texts, which still contained many brackets and options, i.e., different versions of what could end up in the final document. Parties across the board were extremely unhappy and concerned with the text, but for different reasons. There are two core contentious issues in particular where Parties have mutually exclusive preferences: finance and mitigation. If you have followed our chronicles, you are already a little informed about the finance controversies: how much finance? Who should pay, and who will be able to benefit from these flows? On mitigation, COP28 agreed to “transition away from fossil fuels” – this was celebrated as a “historic” decision, and many Parties want to repeat that language in Baku. Saudi Arabia in particular—although having agreed to this language last year—does not want any reference to fossil fuels in the text.

The COP29 Presidency is now working around the clock to come up with a new version of the text, expected for noon today, for further negotiations and hopefully a conclusion. Nobody expects this to happen tonight, although this would be the official schedule. But none of the recent previous COPs have ever ended on time, and have sometimes even extended until the early hours of the following Sunday. A long-term observer of the COP process said this morning: the chances of concluding today are zero; those of ending tomorrow stand at 40-50%, and those of ending on Sunday, also at 40-50%. In other words, there is a significant chance that the COP will actually not find a compromise that is acceptable to all…

In its long history, the UNFCCC process has seen only one COP that has not managed to conclude: COP6 in The Hague in 2001. The COP then actually resumed at “COP6bis” in June, at the annual interim negotiation session.

But even if Parties find a way to conclude on Sunday 24 November, this can be problematic for some states. As the Marshall Islands’ negotiator declared during yesterday’s plenary: “A lot of us, we don’t have the luxury of extending [our trips], paying for tickets to change, paying for additional hotel rooms,” she said. “Most countries like mine, we can’t do that, so it’s very hard if it gets pushed.” These challenges for smaller and poorer states directly relate to their being present or not, and so are at the heart of our research project. While the negotiations are thus rather frustrating and the outlook bleak, for our project, COP has been successful. We have been able to observe many different small states and their engagement in the process across different venues—in the negotiation rooms, during side events, at the pavilions, in press conferences; we have been able to network, meet other researchers, and speak with negotiators, with whom we hope to conduct interviews after the COP. It has been interesting, insightful, and intensive—and just like the negotiators, we now look forward to the end and to going home.

Thanks for following!

From Sarah Thompson

As we reach the final days, I have been reflecting on my first COP experience. It has been eye-opening, inspiring and, at times, a bit overwhelming! The sheer scale of the event was staggering, with tens of thousands of participants navigating a maze of negotiations, plenaries, side events, pavilion exhibits, and more. Even planning my daily schedule proved to be an unexpected challenge, with negotiation meeting times often scheduled at the last minute, and having to choose between multiple events taking place at the same time—not to mention finding time to eat and rest! It would be impossible to follow all the many different subjects discussed at COP. Though I was fortunately focused on a single topic relating to my PhD (the NCQG), it was still challenging to attend everything I hoped to, particularly as the NCQG intersects with so many other critical issues.

Nevertheless, being on the ground offered an unparalleled window into the negotiations process in real time. It was fascinating to observe the intricate dynamics between countries and negotiating blocs, as delegates carefully debated sometimes even the most minor of word changes in the texts, knowing that each term may carry a different legal weight. One could say this is multilateralism in action, with all its challenges and compromises! Given that this was dubbed the ‘Finance COP,’ with the NCQG often taking centre stage, there was a palpable sense in these discussions that the stakes were particularly high, knowing that these decisions could carry significant consequences for global climate finance and action in the years to come. However, even in the final hours of the conference, decisions are still pending, and while there was a collective desire to leave Baku with a goal to be proud of, the continued absence of a clear financial commitment (the ‘quantum’) and the persistence of opposing perspectives on the donor base and the type of finance to be included, makes it difficult to envision a promising outcome at this stage.

During the plenaries and particularly the ‘Qurultay’ on November 21, I found the numerous calls for urgent action—especially from developing countries—to be deeply moving, reflecting the existential stakes of the climate crisis. It reminded me of my time many years ago studying at the University of the South Pacific in Fiji, where I had the privilege of learning firsthand from Pacific Islanders about the existential threats they face due to the effects of climate change, such as rising sea levels, extreme weather events, and disappearing coastlines. Their stories then, as now, underscore the human realities behind the statistics and negotiations, which I hope resonated with all COP29 negotiators. However, at the same time, it can be a bit disheartening to witness the replay of continued divisions between the so-called developed and developing nations, highlighting the longstanding challenges to achieving global consensus.

Finally, it was also interesting to witness the heated debates around the hosting of COP29 in a petrostate for the third consecutive year and the presence of over 1,770 fossil fuel lobbyists. Some argued that the energy sector’s involvement is necessary for an inclusive transition, while others accused these actors of obstructing meaningful progress. These tensions highlight the complexity of the dialogue on climate change, where urgency, compromise, and competing interests collide.

Overall, my COP29 experience highlighted both the fascinating complexities and the immense challenges of global climate governance. While the process is far from perfect and not without its shortcomings, it is hard to ignore the many actors worldwide that are committed to collective action. I left with a mix of hope and disappointment, and gratitude to be working alongside so many dedicated individuals on these critical issues!

Final views of the entrance to the COP29 venue at the Baku Olympic Stadium

Final Agreement, Reflections and Expectations

From Sarah Tegas

What was deemed the “finance” COP did little to preserve the hopes of developing and most vulnerable states in agreeing with their counterparts on a quantum that would reflect their realities on the ground. US$300 billion (by 2035) was the final-agreed new annual public climate finance goal. Far from the initially-requested US$ 1.3 trillion, leaving most unhappy. Many ask, what is the point then of all these hours of negotiations for an inadequate and disappointing agreement? Better no deal than a bad deal?

These are questions I constantly receive and ask myself when studying negotiations. Still, I remain convinced that multilateral negotiations are primordial in the fight against climate change. Yearly meetings of all parties to convene, agree to disagree, hear from all perspectives and be reminded of the urgency of the issue at stake will continue to pave the way forward, however slow and cumberstone it might be.

Yet, this COP was particularly saddening to witness. Following closely the positions of AOSIS, least developed countries LMDCs and AILAC, I was moved by interventions from Colombia, Panama, Bolivia, on how indebted their countries already were and how they couldn’t afford to rely on intrusive and prescriptive loans. Colombia is arguing to elevate the political debate and stop with the geopolitical game many are playing. India walked out of COP rejecting the final deal and stating that the document is “nothing more than an optical illusion”. Although agreed upon “consensus”, the deal seems to have been gavelled by the COP29 Presidency, pushing away any objections.

All in all, the final NCQG leaves a gap to be filled, once again putting the stakes high for the next COP host—Belem, in Brazil. I am very eager to follow the Baku to Belem roadmap. After two consecutive years of COPS in oil-rich countries, it’s time to turn to the lung of the planet, the “Amazonia”, and hope that such context will help further cement the “transition away from fossil fuels”, strengthen the voice of indigenous communities and their variety of local knowledge in the climate talks.

Until next year!

The COP 29 stadium, Baku, 20 November 2024

This series of blog posts was originally published on the CERI (Centre for International Studies) website.

Photo credits: Carola Klöck, Sarah Tegas, Sarah Thompson