Fostering the Future of Green Finance: A Look Back at the Green Finance Challenge with HSBC Continental Europe

10 February 2025

Take part in this semester’s student essay challenge on competitiveness in a low-carbon economy!

18 February 2025By Sarah Thompson, PhD Candidate, Université libre de Bruxelles and Senior Research Programme Manager, European Chair for Sustainable Development and Climate Transition, Sciences Po and Romain Weikmans, Professor of International Relations, Center for Research and Studies in International Politics (REPI), Department of Political Science, Université libre de Bruxelles

As 2025 marks the 30th anniversary of the first UN Climate Change Conference (COP), it is an important moment to reflect on how far international climate negotiations have come—and perhaps how far they must still go—especially on the critical issue of climate finance. COP29, held last November in Baku, Azerbaijan, was widely dubbed the “Finance COP” due to its central focus on setting a new global climate finance goal. Climate finance—funds provided to help developing nations mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change—has historically been a point of contention in negotiations, while also serving as a key lever for breaking deadlocks and fostering trust between developed and developing countries.

This blog post will provide an overview of climate finance in COP negotiations, highlight key finance outcomes from COP29, and discuss some of the main critiques of the newly agreed-upon climate finance goal of US$300 billion as we look ahead to COP30 in Belém, Brazil this November.

A brief history of international climate finance goals

Looking back at 2009’s COP15 in Copenhagen, it is often regarded as a resounding failure of the UN climate process. Ending with a text[1] that was not adopted by consensus, it nevertheless launched a promise that would leave a lasting mark on subsequent negotiations. In Copenhagen, developed countries pledged to collectively provide US$30 billion in “new and additional” public resources over three years (2010–2012) to support, in a “balanced” manner, both greenhouse gas emission reductions and adaptation to the impacts of climate change in developing countries. Developed countries also committed to the goal of mobilising US$100 billion annually by 2020, from both public and private sources, to meet the needs of developing nations “in the context of meaningful mitigation actions and transparency on implementation.”

The US$100 billion goal was only put forward by representatives of developed countries in the final hours of COP15 as an attempt to “rescue” the Copenhagen Accord.[2] The deadlock in negotiations was caused by disagreements amongst parties: developed countries wanted all major emitters (notably including China and India) to commit to lowering their emissions, while developing countries insisted rich nations, who have historically caused climate change, should bear the main responsibility under the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities”. In the end, the goal only called on developed countries to contribute to achieving this goal, though even at the time, the US$100 billion amount was widely viewed as woefully inadequate, given the scale of the challenge. Representatives of the G77 and China were advocating for annual financial transfers amounting to roughly 1.5% of the GDP of developed countries—totalling over US$700 billion per year by 2020.[3]

Nevertheless, the goal was agreed upon and several years later, in 2015 at COP21 in Paris, countries agreed to extend the US$100 billion annual goal to 2025 and to establish a “New Collective Quantified Goal” (NCQG) before 2025.[4] Setting this new goal would also involve a multi-year deliberative process between developed and developing countries, ensuring that the new target would take into account the needs of developing nations.

Meeting the US$100 billion goal: Success or shortfall?

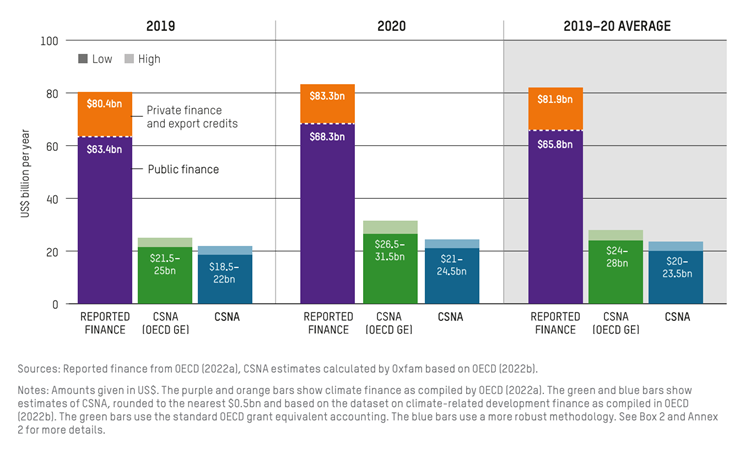

As the NCQG was being deliberated at COP29, negotiators pointed to either the success or failure of the US$100 billion goal, depending on which party was speaking. However, the goal was framed in terms so vague that it is impossible to clearly and definitively state whether it has been met.[5] Nevertheless, all countries agreed that it was not achieved by the original deadline of 2020.[6] Beyond this, there is no consensus on the current level of financial mobilisation. According to the OECD, which relies on self-reported data from developed countries, the target was surpassed for the first time in 2022[7], with climate finance reaching approximately US$116 billion, including US$22 billion from private financing. However, many representatives of developing countries and civil society dispute these claims. Oxfam, which publishes an annual counter-report[8] to the OECD’s findings, estimates that the actual financial mobilisation is about three times lower.

Similar patterns can be observed in the years prior, as well. The graph below, taken from Oxfam’s 2023 report, compares reported climate finance by the OECD with Oxfam’s more conservative estimates for 2019 and 2020. While OECD figures suggest public contributions of around US$66 billion per year, Oxfam’s estimates indicate that the actual support reaching developing countries could be significantly lower—between US$20 billion and US$23.5 billion annually during this period. Oxfam’s calculations adjust for several factors that may overstate reported public climate finance. These include grant equivalency (GE)—which accounts for the ‘real value’ of concessional loans—, the actual benefit to recipient countries, and the proportion of funds explicitly dedicated to climate action. As a result, Oxfam presents a climate-specific net assistance (CSNA) estimate, offering a potentially more accurate reflection of developed countries’ financial effort.

Source: Climate Finance Shadow Report 2023: Assessing the delivery of the US$100 billion commitment

As for which developed countries were better or worse performers, it is worth recalling that the US$100 billion target was collectively formulated without a clear allocation of effort among them. However, when considering historical responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions and financial capacity, it is fairly easy to identify a notable underperformer: the United States, which provides relatively little climate finance in light of these two factors. While President Biden previously committed[9] to boost their climate finance contributions to more than US$11.4 billion annually by 2024, the new Trump administration seems keen to reverse this progress: on his first day in office, President Trump already pledged to cut international climate funding and withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement.

The complexity of counting climate finance

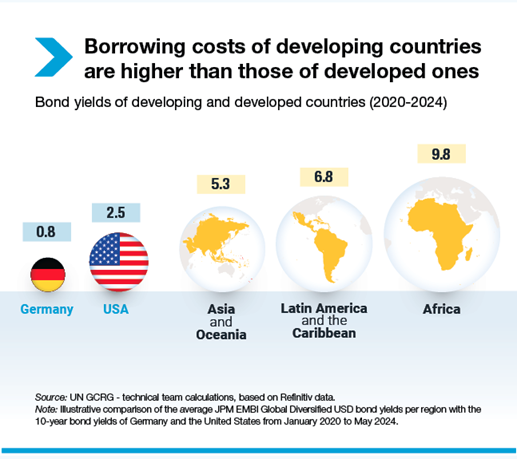

Owing in large part to the absence of a universally agreed-upon definition, climate finance accounting is riddled with controversies.[10] For example, most developed countries that provide part of their climate finance in the form of loans account for them in the same way as they do grants. A loan of €50 million, therefore, would appear identical to a €50 million grant in the figures reported to the OECD or the Secretariat of the Climate Convention—even though the loan will, of course, need to be repaid, most often with interest. It is worth noting that around 70% of climate finance today is provided as loans[11], a fact that deeply concerns many representatives of developing countries and civil society organisations. Loans risk pushing already vulnerable nations further into debt as they face debt servicing costs much higher than those paid by developed countries—ranging from 2 to 4 times higher than interest rates paid by the United States and 6 to 12 times higher than those paid by Germany[12]. These financial pressures severely limit their ability to adapt to or mitigate climate change impacts, let alone address loss and damage.

Source: A world of debt 2024 | UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

This method of equating loans with grants also complicates the comparison of financial contributions among developed countries. For instance, nations such as France and Japan provide the majority of their financing in the form of loans—which ‘inflates’ their figures—whereas others, like Sweden or Belgium, deliver almost all their financing as grants.

The COP15 decision text[13] stated that climate finance should be “scaled up, new and additional, predictable and adequate funding,” meaning that it should not replace or divert funds earmarked for development assistance, for example. Yet a report from CARE[14] found that a startling 93% of climate finance reported by developed countries between 2011 and 2020 was not actually ‘additional’; instead, it comprised funds that were reallocated away from development aid. Only Luxembourg, Norway, and Sweden were found to have adopted a more stringent approach of classifying their climate finance as flows that exceed the development assistance target of 0.7% of gross national income and consistently surpassing these commitments.

The vague definition of climate finance and the absence of third-party oversight have also allowed some developed countries to exploit these loopholes by reporting a number of projects unrelated to climate action as part of their climate finance contributions. For instance, Italy provided funds to open chocolate and gelato stores across Asia, the United States provided a loan for an hotel expansion in Haiti, Belgium promoted the film “La Tierra Roja,” a love story set in the Argentine rainforest, and Japan financed a coal plant in Bangladesh and an airport expansion in Egypt.[15] Each country attempted to establish some connection between these projects and climate change or environmental protection to justify their financial backing, though these links were tenuous at best. These were just five projects, yet they collectively amounted to US$2.6 billion[16]—a notable sum relative to the total amount of reported climate finance. Combined with the fact that most reported climate finance is distributed as loans that require repayment, these accounting deficiencies taken together ultimately risk threatening the effectiveness of climate finance and its ability to deliver meaningful support to developing nations.

Key finance outcomes from COP29

In the lead up to COP29, several key issues regarding the new climate finance goal were being hotly debated such as how it would be structured (e.g., balance between public and private funds), the ‘quantum’ (the amount of money to be mobilised), and the donor base (who should contribute). The first week of negotiations on the NCQG kicked off with the scrapping of a text that had been under development for the past year, essentially forcing negotiators back to the drawing board. As the days went on, frustration mounted as developed-country groups refused to propose a quantum, indicating they would not provide a hard number until they knew who would contribute and what kinds of funds would count. Following two weeks of negotiations that went into overtime, as well as a brief walkout by climate-vulnerable nations, a draft decision document[17] was eventually adopted, outlining central components of the new climate finance package:

- All actors (developed and developing countries, multilateral development banks, private sector, etc.) are called to work together in scaling up climate finance to US$1.3 trillion per year by 2035.

- Developed countries will ‘take the lead’ in the new goal of mobilising at least US$300 billion per year by 2035, with funds coming “from a wide variety of sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral, including alternative sources”.

- Developing countries are encouraged to contribute on a voluntary basis (South—South cooperation).

While critics denounced the new US$300 billion goal as insufficient and detached from the needs of developing countries, it is important to consider that an agreement on the goal was far from guaranteed. While the objective of mobilising “at least” US$300 billion by 2035 is distant and lacks ambition, it at least does not represent a major step back from current financial mobilisation levels—which are unquestionably both deeply unsatisfactory for many developing countries and wholly insufficient to address the scale of the climate crisis. Faced with current geopolitical and economic challenges—including cost-of-living crises in many developed countries and the United States’ withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, which could have prevented any new goal from being adopted—it is crucial to recognise the significance of reaching any agreement on a new target.

There was also a decision to continue efforts to triple the disbursements of funds established under the Climate Convention[18] by 2030 (compared to 2022 levels) to support climate action in developing countries. It is worth noting, however, that these funds, despite attracting significant media attention, account for only a small portion of international climate finance. In 2022, for example, these funds only disbursed US$1.74 billion; if realised, the tripling of these disbursements would amount to a bit more than US$5 billion by 2030. The role of these funds established under the UNFCCC will therefore remain relatively modest, as developed countries prefer to channel their financing through other institutions, primarily bilateral development agencies and multilateral development banks such as the World Bank.

Who will contribute to the new climate finance goal?

The 1992 Climate Convention clearly distinguishes between “developed” and “developing” countries based on their historical responsibility for climate change, varying levels of capacity, and on principles of equity. These categories have remained unchanged for over 30 years, despite some “developing” nations, such as Singapore and Gulf oil states, now having a GDP per capita higher than many countries in the European Union, and other “developing” countries like China, Brazil, and India being amongst the top greenhouse gas emitters. While India’s per capita emissions remain relatively small, China’s per capita emissions are currently higher than those of the European Union (but significantly lower than those of the United States).[19] In addition, the historical emissions of China (since 1850) have surpassed those of the European Union (yet remain far below those of the United States).[20]

In response to the evolving economic and emissions landscape, developed nations have long insisted that they should no longer bear sole responsibility for supporting developing countries in addressing climate change and its effects. They have partly succeeded, as the NCQG decision text calls on developed countries to lead the mobilisation of US$300 billion, implying they will not be the only contributors. That said, countries like China have already been significantly funding mitigation and adaptation projects in other developing nations for several years.[21] While developing countries are now encouraged to contribute to the US$300 billion target and report their contributions to the Climate Convention Secretariat, it remains to be seen the extent to which they will do so, as developing-country contributors have so far refrained from reporting these data to the Secretariat.

Notably, all disbursements from multilateral development banks (such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and European Investment Bank) will now count towards the US$300 billion target by 2035. This is a significant change since, previously, only the share attributable to developed countries was counted towards the US$100 billion goal. This means that climate finance indirectly provided by developing countries to other developing countries through multilateral development banks will now be included. This shift is noteworthy: in 2022, for instance, US$50 billion of climate finance channelled through multilateral institutions was attributed to developed countries, while US$20 billion was attributable to developing nations.[22] These figures illustrate that developing countries are already making substantial contributions to international climate finance. In addition, the main multilateral development banks—including the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank but also non-Western backed institutions such as the Islamic Development Bank and the New Development Bank—announced on the second day of COP29 that their collective climate financing for low- and middle-income countries would reach US$120 billion by 2030.[23]

Furthermore, this change in methodology means that the portion of climate finance provided via multilateral development banks attributable to the United States (through its contributions to these banks’ capital) will continue to count towards the US$300 billion target. This will occur even though they are withdrawing from the Paris Agreement and will “cease and revoke any purported financial commitment…under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change”.[24] However, the United States could attempt to push some multilateral banks, such as the World Bank, to scale back their climate efforts. This will be an area to watch closely.

Critiques of the new US$300 billion goal

Heading into COP29, the expectations for the new climate finance goal were enormous. The Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance estimated that investments (public and private, domestic and international) of between US$3.6 trillion and US$3.9 trillion per year would be needed by 2030 to support a “just energy transition, adaptation and resilience, loss and damage, and nature conservation and restoration” in all developing countries.[25] Based on this, the two co-chairs of the Expert Group suggested that the NCQG should be at least US$300 billion by 2030 and US$380 billion by 2035.[26]

Other figures were also proposed by representatives of developing countries. For example, the African Group of Negotiators called for US$1.3 trillion per year to be provided to developing countries by developed nations between 2026 and 2030, totalling US$6.5 trillion over five years.[27] Similarly, the Like-Minded Developing Countries—a coalition representing more than 50% of the world’s population, including China, India, and Saudi Arabia—proposed US$1 trillion annually for the same period.[28] Crucially, it was demanded that these funds come from public sources, be accounted for as grant equivalents, and be “new and additional” to existing development aid. In addition, there were also calls from Small Island Developing States and Least Developed Country groups to set minimum allocation floors for their nations given their acute needs, as well as proposals for specific sub-goals on adaptation and loss and damage funding.

The outcome of COP29 falls far short of these demands. The US$300 billion target encompasses both public and private funds, with no clarity on their respective shares, is accounted for at face value (treating loans and grants the same), and includes no specifications about the “new and additional” nature of the funds. In this regard, the US$300 billion target follows the same accounting rules as the previous US$100 billion goal, despite calls for increased clarity on what should count as climate finance under the NCQG. Moreover, the decision text for the US$300 billion explicitly states that developed countries will no longer be the sole contributors to this collective financial mobilisation goal, as they were for the US$100 billion target, which signals a shift from past understandings of the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities”. Furthermore, the lack of agreement on subgoals under the NCQG—such as specific allocations for vulnerable country groups or dedicated funding for adaptation and loss and damage—risks perpetuating underfunding in critical areas and maintaining the current imbalance between mitigation and adaptation financing.

It is also worth noting that while the COP29 decision text mentions the figure of US$1.3 trillion, it does so in a highly unsatisfactory manner for many developing countries and civil society organisations. By merely calling on all actors to collaborate in mobilising at least US$1.3 trillion annually, the statement sets a highly aspirational target but lacks a clear or realistic pathway for achieving it. The decision acknowledges numerous obstacles to achieving this but defers addressing them to future discussions or other entities.

As for establishing procedures to ensure funds are used for climate-related purposes, COP29 did not make any progress in this regard, either. Each contributor will continue to retain full sovereignty over what it counts as “climate finance.” There are likewise still no formal mechanisms to prevent a country from diverting development assistance to climate efforts, nor to stop countries from providing financial support labelled ‘climate finance’ for projects, such as the previously mentioned coal plants, airport expansion, and gelato shops.[29]

Despite these criticisms, in the final hours of COP29, the decision on the NCQG was adopted by all parties. However, shortly after the gavel fell, India addressed the COP Presidency and voiced strong objections to the agreed-upon text: ‘rejecting’ its hurried approval, calling out the lack of ambition from developed countries, and claiming that the standard due process was not respected.[30] Nevertheless, while India’s objections were noted in the official records, the country did not actually seek to block the adoption of the decision text. Their choice to speak out after the gavel fell allowed them to express the strong discontent felt across many developing countries and civil society and show solidarity with the Global South, stressing the need for more support from developed nations.

Navigating geopolitical tensions on the road to Belém

While the impact of Trump’s re-election on COP29’s outcome was significant, more broadly, recent elections in many countries have also brought to power leaders who do not prioritise climate action. Adding to this, the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, and the resurgence of trade tensions between China, the European Union, and the United States have created an unfavourable context for climate multilateralism. To make matters worse, the Azerbaijani presidency, which was prone to provocation, continuously fuelled North-South divisions and has been scrutinised for lacking inclusivity and transparency in their management of the negotiations. Combine this with the highly sensitive issue of financial transfers between developed and developing countries, and an extremely volatile situation arises. COP29 was undoubtedly one of the toughest in recent years, with exceptionally high levels of tension.

A key point underlining ongoing climate finance negotiations concerns the fact that the current and future growth in greenhouse gas emissions occurs predominantly in developing countries and will continue to do so. If these nations are not supported or incentivised to decarbonise their economies, global warming will reach alarmingly high levels. Beyond this issue of effectiveness, there are also fundamental questions of justice: the poorest countries in the world bear minimal historical responsibility for climate change yet suffer its effects most acutely. For these nations, financing for adaptation and compensation for loss and damage are critical issues.

As the world looks toward COP30 in Belém, Brazil this coming November, climate finance will remain central to climate negotiations and undoubtedly continue to be a divisive issue. The coming year will see the latest submissions of Nationally Determined Contributions—climate action plans submitted by countries outlining their efforts to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change, as part of their commitments under the Paris Agreement. This process will be crucial for clarifying the implementation of the NCQG, particularly in defining a roadmap of how countries will achieve the ambitious target of US$1.3 trillion. Developing nations and civil society will likely continue pushing for greater ambition, especially regarding predictable and additional funding. However, the Unites States’ withdrawal from the Paris Agreement and cutting its climate finance provisions, alongside growing economic pressures in key contributing countries, could spark a wave of weakened commitments. Brazil’s presidency will have to navigate these geopolitical tensions while working to bridge the divide between developed and developing nations, particularly as it positions itself as a leader of the Global South. Whether Belém delivers meaningful progress will depend largely on whether nations can overcome political inertia and raise the level of ambition to align themselves with the Paris Agreement and core principles of the UN Climate Convention.

[1] https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2009/cop15/eng/l07.pdf

[2] https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/normative-foundations-of-international-climate-adaptation-finance/7BD86C68DEE5F83E5765FCFE7469B593

[3] https://www.twn.my/title2/climate/pdf/fair_and_effective_climate_finance/Finance%20Assessment_En_Final.pdf

[4] https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/fre/10a01f.pdf

[5] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-021-00990-2

[6] https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma2021_L16_adv.pdf

[7] https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/climate-finance-provided-and-mobilised-by-developed-countries-in-2013-2022_19150727-en.html

[8] https://www.oxfamnovib.nl/Files/rapporten/2024/Climate%20Finance%20Short-Changed%202024.pdf

[9] https://www.nrdc.org/bio/joe-thwaites/how-us-can-still-meet-its-global-climate-finance-pledges

[10] https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/climate-change-finance/

[11] https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/climate-finance-provided-and-mobilised-by-developed-countries-in-2016-2020_286dae5d-en.html#:~:text=This%20report%20provides%20disaggregated%20data%20analysis%20of%20climate,climate%20finance%20components%2C%20themes%2C%20sectors%2C%20and%20financial%20instruments

[12] https://unctad.org/publication/world-of-debt

[13] https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2009/cop15/eng/l07.pdf

[14] https://www.care-international.org/resources/seeing-double-decoding-additionality-climate-finance

[15] https://www.wri.org/insights/debt-climate-action-developing-countries

[16] Idem.

[17] https://unfccc.int/documents/643641

[18] These include the Green Climate Fund, the Global Environment Facility, the Loss and Damage Fund, the Adaptation Fund, the Least Developed Countries Fund, and the Special Climate Change Fund.

[19] https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/report_2024

[20] https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-chinas-emissions-have-now-caused-more-global-warming-than-eu/

[21] https://www.wri.org/insights/china-climate-finance-developing-countries

[22] https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/climate-finance-provided-and-mobilised-by-developed-countries-in-2013-2022_19150727-en.html

[23] https://www.eib.org/files/press/FinalJointMDBStatementforCOP29.pdf

[24] https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/putting-america-first-in-international-environmental-agreements/

[25] https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Raising-ambition-and-accelerating-delivery-of-climate-finance_Third-IHLEG-report.pdf

[26] https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/news/joint-statement-by-amar-bhattacharya-vera-songwe-and-nicholas-stern-co-chairs-of-the-independent-high-level-expert-group-on-climate-finance/

[27] https://unfccc.int/documents/640343

[28] https://unfccc.int/topics/climate-finance/workstreams/new-collective-quantified-goal-on-climate-finance/written-inputs-received-from-parties-to-inform-the-preparation-of-an-updated-input-paper-ahead-of

[29] https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/climate-change-finance/

[30] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=srS74r4tOJw

This blog post builds on an interview of Prof. Romain Weikmans published in December 2024 in the 36ème Lettre de la Plateforme wallonne pour le GIEC. The authors acknowledge financial support from the European Chair for Sustainable Development and Climate Transition, Sciences Po (Sarah Thompson) and from the Belgian Dialogue on Climate Foreign Policy funded by the Helios Foundation (Romain Weikmans).