Migration, Wages and (un)Employment

16 November 2020

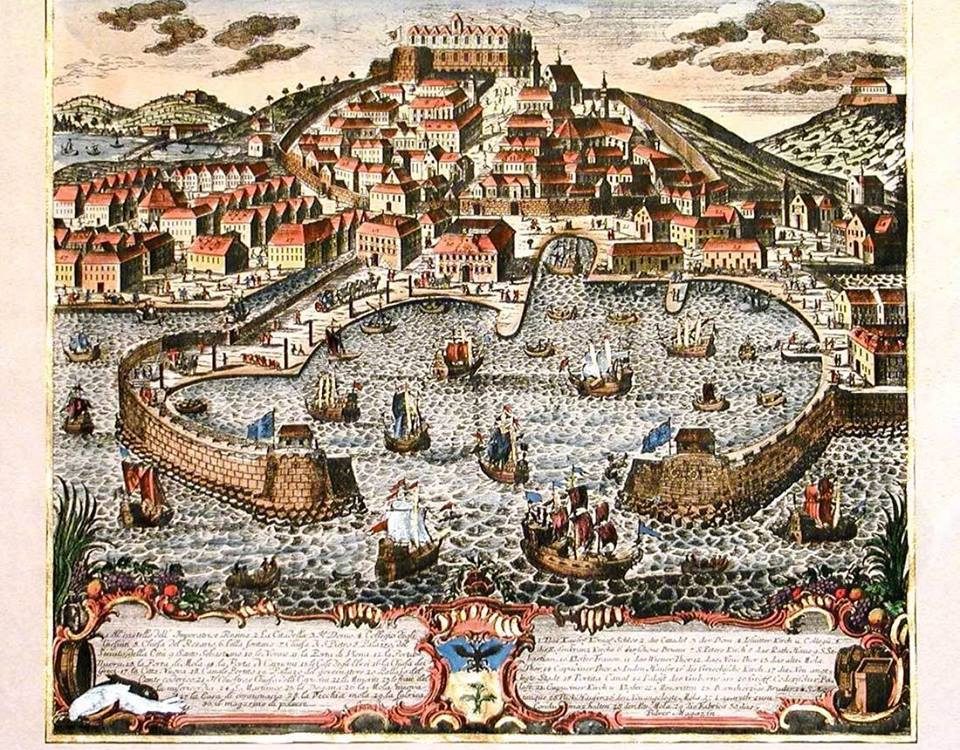

Before the Deluge

16 November 2020A Comparative Cultural Analysis of Columbian and American Jurisprudence

by Louis Imbert

Foreigners are not exempt from the vision of the law proposed by American anthropologist Clifford Geertz, who claimed that it is simply “a specific manner of imagining reality”(1)Clifford Geertz, « Local Knowledge: Fact and Law in Comparative Perspective », in Clifford Geertz, Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology, Basic Books, 1983, p. 173.. While the foreigner as a figure is certainly a social construct, law plays a fundamental role in this construction(2)Danièle Lochak, Étrangers : de quel droit ?, PUF, 1985, p. 7-8..

© Jorm S, Shutterstock

Legal categories make the distinction between nationals and foreigners as well as between foreigners both natural and legitimate. They have considerable symbolic effects, beyond the impact they have on the daily lives of these foreigners(3)Ségolène Barbou des Places, « Les étrangers ‘saisis’ par le droit : Enjeux de l’édification des catégories juridiques de migrants », Migrations Société, vol. 128, n° 2, 2010, p. 33-49. Law thus defines “symbolic borders” that enable the “construction of a fictitious community”(4)Marie-Laure Basilien-Gainche, « Les frontières européennes. Quand le migrant incarne la limite », Revue de l’Union européenne, n° 609, juin 2017, p. 7. See also Michael Scaperlanda, « Partial Membership: Aliens and the Constitutional Community », Iowa Law Review, vol. 81, n° 3, mars 1996, p. 707-773. This observation is highlighted by analysis of constitutional jurisprudence in the field of immigration. There are many examples of legal discourses on foreigners that are intended to justify the specific solutions designed for them. The power of such discourses with respect to the construct of the foreigner is all the more striking when compared according to a cultural approach.

Compare to Explain

According to the cultural approach adopted herein, the law is considered as a specific “symbolic form”, just like art or religion. It does not merely reflect a “style of social existence”, it helps to define it(5)Clifford Geertz, « Local Knowledge: Fact and Law in Comparative Perspective », op. cit., p. 218.. Cultural analysis thus aims to produce a “dense description” of the meanings constructed by law(6)This approach means delving into a specific context to discover a “multiplicity of complex conceptual structures, many of them superimposed upon or knotted into one another, which are at once strange, irregular, and inexplicit, and which [the ethnographer] must contrive somehow first to grasp and then to render” (Clifford Geertz, « Thick Description: Towards an Interpretive Theory of Culture », in Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures, Basic Books, 1973, p. 10). See also Paul W. Kahn, The Cultural Study of Law: Reconstructing Legal Scholarship, University of Chicago Press, 1999. For a study of the “formulation of modes of existence” in European immigration law, see. Loïc Azoulai, « Le droit européen de l’immigration, une analyse existentielle », R.T.D. Eur., 2018, p. 519-539. . Comparison is one of the best ways of doing this. Even if the law “operates under local knowledge”, comparing legal discourses of different origins improves our understanding: “one lightens what the other darkens”(7)Clifford Geertz, « Local Knowledge: Fact and Law in Comparative Perspective », op. cit., p. 167 et 233. Voy. également Günter Frankenberg, Comparative Law as Critique, Edward Elgar, 2016. .

© ImageFlow, Shutterstock

In this light, we can compare the jurisprudential treatment of immigration in the USA and Columbia.

Two Countries, Two Legal Configurations

In the USA, immigration has been a major issue for years and has been the subject of countless Supreme Court cases since the last quarter of the 19th century. The interest of the American jurisprudential construction notably resides in the early and persistent recognition by the Supreme Court of the plenary power, i.e. of very broad scope, of the legislative and administrative authorities in all matters relating to immigration (entry, residence and deportation). This results in very restricted judiciary power over the decisions of these authorities.

In contrast, Colombia has long been a country primarily of emigration and the issues related to welcoming immigrants are recent ones. Examination of the jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court of Colombia, innovative and progressive in many areas, shifts the centre of the analysis, while most comparative studies on constitutional and immigration law are almost exclusively focussed on the same systems of the northern hemisphere (principally Europe and North America).

USA, Pioneer of the Legal Construct of the Foreigner

United States Supreme Court © Orhan Cam/Shutterstock

The difference between nationals and foreigners is still significant today in US constitutional law. While the former have a permanent right to enter and reside on the national territory, the latter find themselves in an ambiguous legal situation, that critical American studies on this topic have described using terms such as “strangers to the Constitution”(8)Gerald Neuman, Strangers to the Constitution: Immigrants, Borders and Fundamental Law, Princeton University Press, 1996., “impossible subjects”(9)Mae Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America, Princeton University Press, 2014. and even “nonpersons”(10)Kevin R. Johnson, « ‘Aliens’ and U.S. Immigration Laws: The Social and Legal Construction of Nonpersons », University of Miami Inter-American Law Review, vol. 28, n° 2, hiver 1996-1997, p. 263-292. . One of the particularities of these legal subjects is their deportability, because they are always liable to be deported from the national territory(11)Nicholas de Genova, « Migrant ‘Illegality’ and Deportability in Everyday Life », Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 31, 2002, p. 419-447 ; Abdelmalek Sayad, « Immigration et ‘pensée d’Etat’ », in La double absence. Des illusions de l’émigré aux souffrances de l’immigré, Seuil, coll. « Points », 1999, pp. 507-508..

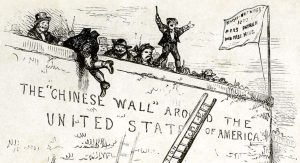

In the 1889 “Chinese Exclusion Case” (Chae Chan Ping v. United States), the Supreme Court ruled that the “power of exclusion of foreigners” was an “incident of sovereignty belonging to the government of the United States as part of those sovereign powers delegated by the constitution”. It considered that the claim “was not a matter for judicial cognizance” and that knowing that “the government of the United States, through the action of the legislative department, can exclude aliens from its territory” was not a fact “open to controversy”. A logical and obvious power.

In the Nishimura Ekiu v. United States (1892) decision, the Court confirmed this position, ruling that “It is an accepted maxim of international law that every sovereign nation has the power, as inherent in sovereignty, and essential to self-preservation, to forbid the entrance of foreigners within its dominions, or to admit them only in such cases and upon such conditions as it may see fit to prescribe”.

Cartoon by Thomas Nast in Harper’s Weekly about Chinese Exclusion, 1882

Finally, in 1893, in the Fong Yue Ting v. United States case, the Court extended its reasoning beyond the entry of foreigners to include their deportation. It considered that “The right to exclude or to expel all aliens, or any class of aliens, absolutely or upon certain conditions, in war or in peace, [is] an inherent and inalienable right of every sovereign and independent nation, essential to its safety, its independence, and its welfare

These three decisions, made within a few years of one another, form the foundations of the doctrine of “plenary power”, that was repeatedly confirmed throughout the next century. In 1972, the Supreme Court reiterated that “Over no conceivable subject is the legislative power of Congress more complete than it is over the admissions of aliens” (Kleindienst v. Mandel). It was reaffirmed again, in 2018, to justify the very rigorous controls of the “Muslim Ban” (Trump v. Hawaii)(12)The “Muslim Ban” refers to a series of decisions made by President Donald Trump in 2017 to limit entry to the US territory by nationals from a number of countries whose populations are largely Muslim. The Supreme Court cleverly avoided the issue of religious discrimination by wielding the doctrine of “plenary power”. . Thus, in spite of strong doctrinal opposition to the principle of plenary power, it has remained largely intact, with the exception of a few inflections. Incidentally, this jurisprudence has had a considerable influence in many other countries since the end of the 19th century.

Colombia, an Inverted Mirror?

Welcome to Colombia sign, after passing thru immigration controls. 8 September 2011. Crédits : Guillec96, CC BY-SA 3.0

Although Colombia could hardly be considered as an immigration country until recently (in fact, the opposite was true), the issue of migration has become increasingly pressing in the past few years, notably due to the massive influx of Venezuelans escaping from the growing humanitarian and political crisis in their homeland. Almost one and a half million Venezuelans now live in Colombia.

Although the response of this new host country may legitimately raise some criticism, it corresponds, more or less, to an inverted mirror image of European and North American immigration policies. Aside from the mass regularisations implemented by the administrative authorities, the jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court of Colombia, recently held up as an example by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and by several entities of the United Nations, is of particular interest in this matter.

Although the Court constantly recognises a discretionary power (not without limits) to the legislative and executive powers with regard to immigration, two recent decisions offer a striking contrast with the USA and Europe in the terms of the reasoning adopted by the constitutional judges, in a context unanimously referred to as an immigration crisis. In its decisions of 15 November 2017 (SU677/17) and 1 June 2018 (T-210/18), the Court examined cases brought against the administrative authorities by irregular Venezuelan nationals complaining that they were unable to access free health services because of their administrative status. Adopting the exact opposite position to that applied for decades by supreme jurisdictions, administrative authorities and legislators in North America and Europe(13)See Louis Imbert, « Du Palais des Droits de l’Homme au Palais-Royal : chronique d’un renoncement jurisprudentiel face à l’argument de la crise migratoire », RDLF 2019 chron. 38. , the Colombian Court considered that a crisis situation (described here as humanitarian) reinforced—rather than limited—the protection of the fundamental rights (the right to healthcare in this particular case) of the Venezuelan nationals present in Colombia, even and above all those without documentation. The Court particularly insisted on the duty of solidarity of the national community, citing articles 1 and 95 of the 1991 Constitution.

Venezuelan people cross the border to get to Colombia. Crédits photo ; UNHCR/ Vincent Tremeau

The Court also identified the current difficulties of Venezuelan citizens to obtain passports in their country and deduced that, in practice, Colombian immigration rules made it difficult for them to rectify their situations, thus making it impossible for them to sign up for the social security system to access healthcare. However, this position is a paradox in itself. On the one hand, the Court determined that the foreign nationals had a duty to comply with immigration law. On the other, it also claimed that this same legislation made foreigners vulnerable by trapping them in illegal situations. Thus, two radically different approaches—one of control, the other of protection—come head to head, without either prevailing entirely.

In any case, the striking contrast with the protectionism observed elsewhere in situations of “massive inflows” highlights the extent to which the approach adopted to a situation perceived as an immigration crisis is actually a deliberate choice by a judge. Far from being neutral, this choice reflects a certain conception of foreigners and the hospitality to be extended to them. Thus, our complex, changing and sometimes contradictory perceptions of foreigners are built and rebuilt over and over by these legal decisions, notably through the constant redefinition of the meanings associated with foreigners in our constitutional jurisprudence(14)On the concept of legal perceptions, see Jean-François Kerléo, « L’imaginaire : un outil méthodologique d’analyse du droit », Revue internationale de sémiotique juridique, vol. 28, n° 2, juin 2015, p. 359-370. .

Louis Imbert has been a doctoral student of the law school since 2017 and an ATER (temporary research and teaching assistant) in public law at CY Cergy Paris University since 2020. His thesis, entitled “The constitution of foreigners: comparative analysis of discourses of constitutional judges (Columbia, USA, France)” is supervised by professors Guillaume Tusseau and Serge Slama. Louis is the author of several publications on immigration law.

Notes

| ↑1 | Clifford Geertz, « Local Knowledge: Fact and Law in Comparative Perspective », in Clifford Geertz, Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology, Basic Books, 1983, p. 173. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Danièle Lochak, Étrangers : de quel droit ?, PUF, 1985, p. 7-8. |

| ↑3 | Ségolène Barbou des Places, « Les étrangers ‘saisis’ par le droit : Enjeux de l’édification des catégories juridiques de migrants », Migrations Société, vol. 128, n° 2, 2010, p. 33-49 |

| ↑4 | Marie-Laure Basilien-Gainche, « Les frontières européennes. Quand le migrant incarne la limite », Revue de l’Union européenne, n° 609, juin 2017, p. 7. See also Michael Scaperlanda, « Partial Membership: Aliens and the Constitutional Community », Iowa Law Review, vol. 81, n° 3, mars 1996, p. 707-773 |

| ↑5 | Clifford Geertz, « Local Knowledge: Fact and Law in Comparative Perspective », op. cit., p. 218. |

| ↑6 | This approach means delving into a specific context to discover a “multiplicity of complex conceptual structures, many of them superimposed upon or knotted into one another, which are at once strange, irregular, and inexplicit, and which [the ethnographer] must contrive somehow first to grasp and then to render” (Clifford Geertz, « Thick Description: Towards an Interpretive Theory of Culture », in Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures, Basic Books, 1973, p. 10). See also Paul W. Kahn, The Cultural Study of Law: Reconstructing Legal Scholarship, University of Chicago Press, 1999. For a study of the “formulation of modes of existence” in European immigration law, see. Loïc Azoulai, « Le droit européen de l’immigration, une analyse existentielle », R.T.D. Eur., 2018, p. 519-539. |

| ↑7 | Clifford Geertz, « Local Knowledge: Fact and Law in Comparative Perspective », op. cit., p. 167 et 233. Voy. également Günter Frankenberg, Comparative Law as Critique, Edward Elgar, 2016. |

| ↑8 | Gerald Neuman, Strangers to the Constitution: Immigrants, Borders and Fundamental Law, Princeton University Press, 1996. |

| ↑9 | Mae Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America, Princeton University Press, 2014. |

| ↑10 | Kevin R. Johnson, « ‘Aliens’ and U.S. Immigration Laws: The Social and Legal Construction of Nonpersons », University of Miami Inter-American Law Review, vol. 28, n° 2, hiver 1996-1997, p. 263-292. |

| ↑11 | Nicholas de Genova, « Migrant ‘Illegality’ and Deportability in Everyday Life », Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 31, 2002, p. 419-447 ; Abdelmalek Sayad, « Immigration et ‘pensée d’Etat’ », in La double absence. Des illusions de l’émigré aux souffrances de l’immigré, Seuil, coll. « Points », 1999, pp. 507-508. |

| ↑12 | The “Muslim Ban” refers to a series of decisions made by President Donald Trump in 2017 to limit entry to the US territory by nationals from a number of countries whose populations are largely Muslim. The Supreme Court cleverly avoided the issue of religious discrimination by wielding the doctrine of “plenary power”. |

| ↑13 | See Louis Imbert, « Du Palais des Droits de l’Homme au Palais-Royal : chronique d’un renoncement jurisprudentiel face à l’argument de la crise migratoire », RDLF 2019 chron. 38. |

| ↑14 | On the concept of legal perceptions, see Jean-François Kerléo, « L’imaginaire : un outil méthodologique d’analyse du droit », Revue internationale de sémiotique juridique, vol. 28, n° 2, juin 2015, p. 359-370. |