Before the Deluge

16 November 2020

Rereading Fariba Adelkhah: On the Road from Teheran to Damascus

16 November 2020

Malta, Hal Far: tent village, open centre for refugees (mostly boatpeople from Africa), octobre 2009. © Myriam Thyes, CC BY-SA 3.0

Few studies on asylum seekers have explored their place in the production and labor systems of host countries. Migration management certainly gives short shrift to the local labor market, and the success of an asylum application hinges on the candidate’s ability to convincingly claim that s/he is not an “economic migrant”, but rather motivated by factors of a different nature.

However, to consider asylum seekers to be in a unique relationship with the State is to consider them as an exception: a population existing outside the economic and social world. In other words, such a perspective disregards the “invisible threads” (Karl Marx) that bind individuals and place migrants within the “host” society and its production system.

Migrant Labor: a Maltese Perspective

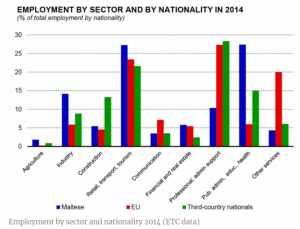

The island of Malta – a member state of the European Union that is close to the Libyan coast from which many asylum seekers depart when attempting to cross the Mediterranean – provides a prime case study for reflecting on how governments address migration and economic accumulation. Based on a qualitative survey that started in 2019 and mainly consists of interviews with various Maltese authorities, local employers, employer organizations, and migrants present on the island, Lucas Puygrenier’s doctoral research explores the interplay between the security and economic dynamics that shape migration and labor policies, turning asylum seekers into a separate workforce on the island.

Between “Burden”…

Malta portrays asylum seekers and refugees as an unbearable “burden” for the microstate, and has a particularly repressive policy towards them. The Maltese military seeks to ensure that the Libyan Coast Guard intercepts migrant boats under a policy of questionable legality(1)Interview with a United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Malta on 25 August. It is also worth mentioning the Amnesty International report, Malta: waves of impunity. Malta’s human rights violations and Europe’s responsibilities in the Central Mediterranean, 7 September 2020..

Detention centers fo migrants. © InfoMigrants

Asylum seekers who do somehow reach the Maltese coast are first incarcerated for a few weeks in detention centers; they are then placed in ‘open centers’ in conditions that non-governmental organisations often denounce. However, Malta also happens to be the European Union country that has recorded the highest rate of economic growth over the past five years (+8.7% per year on average), thanks to a remarkable boom in the tourism and hotel industry and, in particular, the construction sector.

The combination of, on the one hand, the concentration of several thousand people in the island’s “open centers”, many of whom are denied asylum but whom Malta does not have the capacity to deport, and on the other, the growing need for new workers to meet the needs of the local economy, has led employers’ organisations and government authorities to push for the employment of asylum seekers.

… and “Resource”

Source : Maltatoday, 23 June 2016

The search for workers, particularly in construction, combined with employers’ refusal to grant the wage increases demanded by Maltese employees, have turned asylum seekers into an ideal workforce. In 2017, the local Chamber of Commerce urged the government to change its policy to consider migrants no longer as “a burden on society” but rather as “a valuable resource that needs to be mobilized in the most efficient way possible”(2)Malta Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Pre-election proposals : Policy proposals by the Malta Chamber of Commerce and Industry for a competitiveness-centered electoral manifesto, May 2017, pp. 20..

The “resource” that asylum seekers represent is none other than their acceptance of working conditions that few Maltese would. As a case in point, in response to a political opponent who criticised him for the excessive foreign presence on the island during a televised debate in 2019, the Maltese Prime Minister said that he would rather see “foreigners working under the sun” and “collecting rubbish” than his fellow countrymen(3)Caruana Claire, « ‘I don’t want Maltese workers picking up rubbish’ – Muscat », Times of Malta, 2 mai 2019...

Putting Asylum Seekers to Work

Although very few asylum seekers obtain refugee status (only 1,168 people between 2008 and 2018, or 5.7% of asylum seekers registered in Malta during the period), various Maltese authorities recognise their right to work in the absence of residence rights. Out of both economic pragmatism (the country’s need for labor) and political pragmatism (the practical impossibility of expelling those who can legally be expelled), the need to work is strongly impressed upon asylum seekers from the moment they are placed in the “open centers”. They are informed of their right to cursory humanitarian aid (a small financial allowance and accommodation in the center) for up to one year; after that, they are expected to find employment and support themselves. While Malta allows migrants to work legally, it is most often in the informal employment sector that migrants become workers. Work access mainly comes in the form of going to one of the places known to offer work each morning and wait, standing on the street, for the vehicle of an employer (most often a construction sub-contractor) to stop and offer daily work for a few bucks.

For the Benefit of Lean Production

Asylum seekers waiting to be hired as day laborers, Dec. 2019 © Lucas Puygrenier

Observation days conducted at the informal hiring site, and discussions and interviews with those who, as some put it, “wait for the boss” by the road, leave no doubt about the uncertainty that characterises this quest for work. Every day, the majority of those who wait for a potential employer to come by leave empty-handed after several hours of waiting. The classic distinction between the “employed” and “unemployed” therefore largely falls short of describing the unique relationship between migrant populations and work. These migrants might be considered “in between jobs”: they form a labor force that directly participates in value production on an intermittent basis, always awaiting the next job and therefore continuously available to whomever may need them. It is precisely the “storage” of this surplus labor on standby that allows local employers to capitalise on the benefits of lean production through ad hoc expansions of their workforce when needed.

The formation of a migrant labor force therefore involves understanding a government of migration with rationales and modes of action that are not as unequivocal as is often assumed. Both undesirable and useful, marginalised and put to work, the conversion of asylum seekers into workers of a particular kind calls for a more complex analysis and an exploration of the different and sometimes contradictory power dynamics that underlie the situation of migrants within the local capitalist system.

Lucas Puygrenier is a doctoral student in political science at the Center for International Studies (CERI - Sciences Po). His research focuses on changes in capitalism and the governance of production worlds in Malta through the formation of migrant labor. His thesis on "The government of illiberal labor: the institution of migrant labor in Malta", supervised by Béatrice Hibou, analyzes the interrelationship between the marginalization and the employment of migrants in this frontier area of the European Union.

Notes

| ↑1 | Interview with a United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Malta on 25 August. It is also worth mentioning the Amnesty International report, Malta: waves of impunity. Malta’s human rights violations and Europe’s responsibilities in the Central Mediterranean, 7 September 2020. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Malta Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Pre-election proposals : Policy proposals by the Malta Chamber of Commerce and Industry for a competitiveness-centered electoral manifesto, May 2017, pp. 20. |

| ↑3 | Caruana Claire, « ‘I don’t want Maltese workers picking up rubbish’ – Muscat », Times of Malta, 2 mai 2019. |