The Reform of Access to Health Studies in France

12 December 2021

Doping for Work

12 December 2021By Anne-Laure Beaussier, Centre for the Sociology of Organisations

Health care quality has become a subject of constant assessment efforts in many OECD countries. Such ‘quality movement’(1)Bodenheimer T., « The Movement for Improved Quality in Health Care », The New England Journal of Medicine. is driven by many factors including the development of cross-border healthcare, growing public demands for quality care, cost control challenges requiring more efficient and more cost-effective treatments.

Health Secretary Sajid Javid visits Guys and St Thomas hospital, Juin 2021, © UK Government

CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Flickr

However, the proliferation of quality indicators creates more administrative burden for health care organisations and professionals. It also raises a more fundamental issue: the harmonisation of what we mean by quality. There is no unique way of defining, conceptualising and measuring quality of care. The meaning we attribute to quality depends on our own perspective on the healthcare system: for a doctor, quality is not the same as for the manager of a health care establishment, for an insurance provider or for the patients and their experience of the treatment. How we measure quality also differ, with multiple methods for selecting, normalising and aggregating the indicators.

While several international organisations, such as the WHO (Performance Assessment Tool for Quality Improvement in Hospitals), the European Commission (Expert Group on Health Systems Performance Assessment) and the OECD (Health Care Quality Indicators Project Conceptual Framework Paper), support the harmonisation of national health care quality frameworks, the comparative research we present below – conducted in collaboration with researchers from four European countries(2) A more detailed version of this research was published in the Health Policy journal: Beaussier, A. L., Demeritt, D., Griffiths, A., & Rothstein, H. (2020). Steering by their own lights: Why regulators across Europe use different indicators to measure healthcare quality. Health Policy. – highlights differences between European countries in both how quality is understood and how it is measured, which may well hinder any attempt to harmonise national quality assessment frameworks.

Comparing Quality Indicators in Germany, the UK, France and the Netherlands

We selected these four countries on the basis of their geographical and cultural proximity, all having highly performing health care systems, while structured differently. These countries are also representative of the three main families of health care systems: national health system (UK), private health system (Netherlands) and social insurance system (France and Germany).

Charité University Hospital Berlin after renovation in 2016 – INTERRAILS, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia

We chose to restrict our study to indicators assessing hospital quality – the most developed and most comparable – and we performed a term by term comparison of the indicator sets used by national regulatory agencies for quality of care: the Care Quality Commission in the UK, the Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss (G-BA) in Germany; the Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS) in France, and the Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg en Jeugd (IGJ) in the Netherlands. Since some countries use simple indicators while others use composite indicators, to ensure the comparability of our data, we divided the latter into ‘sub-indicators’. We compiled a database of 1,100 indicators: UK (226); Germany (431); France (260); Netherlands (183).

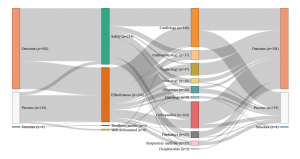

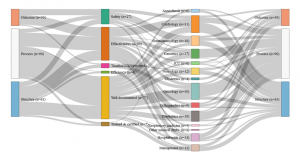

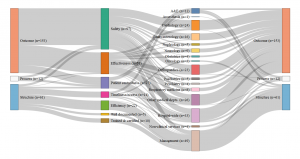

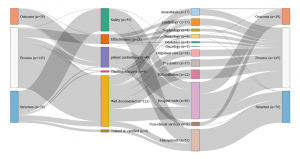

Each indicator was classified according to three families of criteria:

The first comes from Avedis Donabedian’s famous typology of structure, process and results indicators(3)The structure indicators concern financial, material, human and organisation resources used by the healthcare establishment to provide the care (e.g., the number of beds or doctors); process indicators evaluate the way in which care is provided (e.g., is there an anaemia diagnosis before an operation?); finally, result indicators measure the effects of the treatment on the patient’s condition or their level of satisfaction with the care. See: Donabedian A. The Quality of Care: How Can It Be Assessed?, Journal of the American Medical Association, JAMA 1988. We then attempted to identify the primary quality dimensions assessed by each indicator among safety, effectiveness, timeliness and access and efficiency. Finally, we considered which aspects of care were targeted and which ‘part’ of the hospital was evaluated: was it, for example, general measurements at the scale of the hospital or more precise measurements targeting medical practices, such as readmission rates to a cardiology ward after a heart transplant?

Our analysis identified four different profiles and four different ways of understanding and measuring hospital quality. While safety appears to be a shared priority, the four countries also display significant differences in the other dimensions of quality . The UK relies on a very broad definition of quality, however directed in priority towards hospital management; A large share of its quality indicators assess how efficient the hospital management is and how well it optimises its financial and human resources. For this purpose, it uses a range of indicators focusing on the hospital level, such as waiting time, nosocomial infection rates and readmission rates, as well as patient satisfaction with non-clinical services.

Certification des établissements de santé pour la qualité des soins, document édité par la Haute autorité de Santé

Conversely, clinical indicators measuring for instance the implementation of best professional practices are very scarce (two out of 226). The indicator set provides a synoptic view of the quality of care delivered at the hospital level (sometimes even at the ‘trust’ level), but little is done to actually assess the clinical effectiveness of the care delivered by the various departments and specialties individually. The situation is almost the opposite in Germany, where the scope of the indicators is limited, focusing on clinical excellence and practitioners’ adoption of best medical practices. Great emphasis is placed on the intensive monitoring of a limited range of mostly surgical interventions, rather than considering quality at the broader hospital level . The hospital as an organization is barely visible in the indicator set adopted by the G-BA.

Similarly to the UK, in France, quality is mostly measured at the hospital level rather than at the service level and does not assess the skills of individual clinicians. Almost half of the indicators evaluate the quality of patients’ medical records, linking good medical practices with good paperwork. The French indicator seto monitors mostly general hospital functions, such as the catering service, as well as various transversal clinical functions, including pain relief, patient rehabilitation, and the control of nosocomial infections (which represents more than one quarter of the indicators). Apart from a few exceptions, such as psychiatry, for which France has a lot more indicators than any other country, less attention is devoted to monitoring individual interventions or medical specialties.

Finally, in the Netherlands, the IGJ associates quality with clinical governance and measures it in light of the adoption of best professional practices. As in France, there are multiple measurements assessing the quality of the paperwork, however, in the Netherlands, what is targeted is not so much patients’ records than the participation of the hospital to various professional registers and medical societies. Although there are a few indicators assessing transversal dimensions of quality, such as nursing care and human resource management, the emphasis is largely placed on clinical factors. Most of the indicators are focused on the quality of care provided in the different hospital departments and specialties, like in Germany, rather than on the hospital as an organisational unit, like in France or the UK.

- Germany: Set of indicators assessed by the G-Ba (2016)

- Netherlands: Set of indicators assessed by the IGJ (2016)

- England: Set of indicators assessed by the Care Quality Commission (2016)

- France: Set of indicators assessed by the HAS (2016)

Consult the graphics in real size

Interpreting the Variations in National Perceptions of Quality

Overall, in spite of common efforts to regulate care quality, substantial differences remain visible regarding how quality is defined and evaluated in hospitals. France pays attention to how patient medical records are kept, which is something largely overlooked in the other countries. Patient experience is closely monitored in France and the UK, but not by their Dutch and German counterparts. Similarly, economic efficiency is a topic of concern in the UK and, to a lesser extent, in the Netherlands, but not in France or Germany. The UK monitors the largest number of hospital activities, but from afar, while France is the country most concerned with managing the hospital as an organisation.

Institut Néerlandais d’Oncologie (NKI) – Hôpital Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, Amsterdam © Gortemaker Algra Feenstra

These differences reflect the political priorities and objectives of each country; these can be understood by examining the historical and political particularities of each case(4) For France, see Bertillot H (2026). Des indicateurs pour gouverner la qualité hospitalière. Sociogenèse d’une rationalisation en douceur (Indicators to govern hospital quality. Sociogenesis of a gradual rationalisation) Sociologie du travail. For the UK, see Beaussier A-L, Demeritt D, Griffiths A, et al (2026). Accounting for failure: risk-based regulation and the problems of ensuring healthcare quality in the NHS. Health, risk & society. .

In the UK, quality regulation was designed in a context of repeated attempts at reducing costs in the NHS since the 1980s, that led to a number of health scandals involving several hospitals, including the notorious Bristol Royal infirmary in the 1990s, and Mid Staffordshire Hospital Trust in the 2000s. The quality and safety control measures implemented by and after the Blair government can be understood as a response to often contradicting pressures between public demand for quality and efforts to control expenditure and ensure economic efficiency. In Germany, the clinical orientation of the indicators reflects the high level of involvement of health care professionals in designing the quality regulation measures, and the capacity of the leading medical associations to impose their perception of quality on the other corporatist partners. In France, quality regulation is historically linked to the fight against nosocomial diseases and has gradually expanded to include the whole patient experience. It has developed in the context of opposition and mistrust of medical professionals with regard to any evaluation of their professional practices. It is also directed toward ensuring more consistency in patients pathways and coordination between the various professionals participating in the care process. Finally, in the Netherlands, since the 2006 reform privatising the health system and promoting managed competition, the indicators help organise the market: they are mostly focused on supporting patient choices, ensure a level playing field and encourage service providers to compete on quality by comparing safety, efficacy and excellence for a broad range of hospital activities.

The measurement of quality of care is therefore not universal. Choosing to focus on one aspect or dimension of quality is a political decision, associated with the priorities of the nation’s health policies. Any plan to harmonise national quality evaluation systems will include these political choices that are present in the way quality of care is actually understood.

—–

The research presented here is part of a programme on risk regulation in Europe, conducted between 2013 and 2018, based on an ORA project (Open Research Area), with funding from Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR, France), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, Germany), Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC, UK) and Nederlands Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO, Netherlands). Pis : Henry Rothstein, Olivier Borraz, Michael Huber, Frederic Bouder. Research team: David Demeritt, AL Beaussier, Marieke Hermans, Regina Paul, Mara Wesseling, Alfons Bora, Vera Linke, Alexander Griffiths.

Anne-Laure Beaussier is a CNRS Research Fellow at the Sciences Po Centre for the Sociology of Organisations (CSO). Her work, centred on international comparison, concerns risk regulation in Europe and health policies in the USA and Europe. She recently participated in several research projects funded by ESRC and ANR on health insurance in the USA, access to health care in Europe, the regulation of medical care quality in Europe, and risk governance in Europe.

Notes

| ↑1 | Bodenheimer T., « The Movement for Improved Quality in Health Care », The New England Journal of Medicine. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A more detailed version of this research was published in the Health Policy journal: Beaussier, A. L., Demeritt, D., Griffiths, A., & Rothstein, H. (2020). Steering by their own lights: Why regulators across Europe use different indicators to measure healthcare quality. Health Policy. |

| ↑3 | The structure indicators concern financial, material, human and organisation resources used by the healthcare establishment to provide the care (e.g., the number of beds or doctors); process indicators evaluate the way in which care is provided (e.g., is there an anaemia diagnosis before an operation?); finally, result indicators measure the effects of the treatment on the patient’s condition or their level of satisfaction with the care. See: Donabedian A. The Quality of Care: How Can It Be Assessed?, Journal of the American Medical Association, JAMA 1988 |

| ↑4 | For France, see Bertillot H (2026). Des indicateurs pour gouverner la qualité hospitalière. Sociogenèse d’une rationalisation en douceur (Indicators to govern hospital quality. Sociogenesis of a gradual rationalisation) Sociologie du travail. For the UK, see Beaussier A-L, Demeritt D, Griffiths A, et al (2026). Accounting for failure: risk-based regulation and the problems of ensuring healthcare quality in the NHS. Health, risk & society. |