Karl Marx, painted portrait. Crédits : Courtesy of Organ Museum, Thierry Ehrmann, CC BY 2.0, Flickr

On the eve of the 1848 revolution, the founders of contemporary socialism—primarily Karl Marx and Pierre-Joseph Proudh——saw the working class as a unified entity: a revolutionary subject whose action would overthrow the capitalist system and establish socialism. These ideas were quite new at the time. Twenty years earlier, workers were rarely considered as a social class, let alone as the political subject of a socialist ideology. The world of work was often divided into trades, including by the workers themselves. Many reasons drove the conceptual shift, but they are mainly attributable to the emergence of a new take on work, considered as the only activity with economic, political, and moral value. This approach quickly split into two discourses on work: a liberal and a socialist one.

“Get rich!”

The idea of the working class as a unified group defined by a commensurable activity called work is not an invention of revolutionary thinkers. It was first a central element of eighteenth-century physiocratic thought, which distinguished three classes: a “productive” class, an “owner” class, and a third so-called “sterile” class defined as non-agricultural labour(1)Marie-France Piguet, Classe, histoire du mot et genèse du concept: des Physiocrates aux historiens de la Restauration, Presses universitaires de Lyon, 1996.. In the 1820s, this vision of society as divided between classes defined by their position in the production process became part of the conception of history developed by liberal historians such as Augustin Thierry, and even more so François Guizot, leader of the Doctrinaires. According to the latter, modern political institutions—those of representative government——were linked to the rise of the “middle classes”, namely the bourgeoisie. The liberal heirs of the ideas of 1789 considered workers not as part of an organic system of trades, but as free individuals. They were to be pushed to join the middle class by enriching themselves through their work. In 1843, Guizot quipped that workers should “Get rich” in response to demands to expand the right to vote. For the Doctrinaires, work was not enough to grant political rights, especially the vote, which was then reserved for about 5% of adult men. Only the “capable” (capacité), that is to say the most qualified members of society supposedly had the requisite resources to vote.

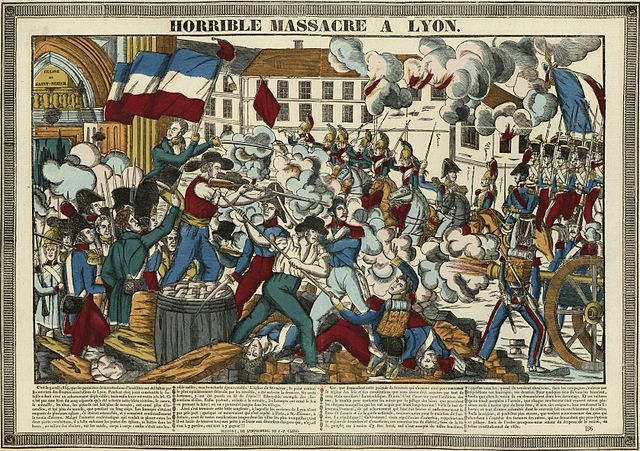

This political devaluation of labour sharpened with the revolution of 1830, which nonetheless revealed the power of Parisian workers. In three days, the monarchy restored in 1815 was defeated, the Duke of Orleans replaced Charles X, and François Guizot entered government. But as soon as the liberals came to power, labour unrest spread, especially in Paris and Lyon, culminating in the insurrection of the Lyon canuts in November 1831. Workers, considered as a block, appeared as a political danger. They were “barbarians”, according to the liberal Saint-Marc Girardin in Le Journal des Débats in December 1831. They needed to be educated by allowing the most deserving to accede to the owner class through their work. In the meantime, the goal of liberals was to get to know these workers and understand why they constituted such a danger.

Revolt of the Canuts of 1834. Colored woodcut, BNF. Public domain

In 1834–1835, the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences commissioned one of its eminent members, the physician Louis-René Villermé, to carry out a vast study on “the physical and moral state of the working classes”(2)François Jarrige et Thomas Le Roux, « Naissance de l’enquête : les hygiénistes, Villermé et les ouvriers autour de 1840 », in Les enquêtes ouvrières dans l’Europe contemporaine: entre pratiques scientifiques et passions politiques, Éric Geerkens et al. (dir), La Découverte, 2019.. After a long career in the army and a study on prisons, Villermé was at the forefront of a new movement of hygienist reformers seeking to diagnose and cure “social infirmities”(3)Annales d’hygiène publique et de médecine légale, prospectus, 1829.. Throughout his study, Villermé tried to establish that the poverty of workers was a moral problem. The living conditions of the workers were better than ever, but they lacked the moral values needed to become rich, and they were often “miserable only through their own fault”(4)Louis René Villermé, Tableau de l’état physique et moral des ouvriers employés dans les manufactures de coton, de laine et de soie., vol. 2,, Jules Renouard, 1840.: “Work to play seems to be the motto for most of them”. The whole moral ambiguity of work as Villermé saw it was that it was a necessary and essentially moralising activity, but also one through which workers, by interacting, could be contaminated by bad morals and dangerous ideas.

Work as a Tool in Fighting Against Liberalism

At the same time, in the 1830s, the situation of workers became a key element of opposition to the liberals who had come to power. Socialists, republicans, and workers organized to form a coalition centred on the idea that there was indeed a working class, unified by labour and subjected to illegitimate political exclusion and a morally unjust system of exploitation. Some of the followers of Saint-Simon played a major role in this process.

Like the physiocrats, Saint-Simon saw society as composed of classes defined by their position in the production process. He saw industrial work not as sterile, but rather as the only economically useful activity. This led him to formulate the founding paradox of this class, which he called the proletariat: the working class is the most useful and the most numerous, and yet it is the poorest.

Claude Henri de Rouvroy de Saint-Simon. Public Domain.

After the death of their leader, the Saint-Simonians organised into a Church based on the concept of New Christianity that they tried to spread, especially among workers. They were soon followed by the republican societies that flourished after the revolution of 1830. The republicans also presented the working class as unified, but above all as politically excluded, since it did not have the right to vote. The Society of the Rights of Man, created in 1832, thus explicitly addressed workers:“The association will count mainly on the support of those who, deprived of their political rights, hardly protected by civil laws, ad made by the rich and for the rich, succumb under the excess of work and the burden of public charges; based on those to whom nature imposes the duty to seize again, if only for their children, their title and their dignity as a man and as a citizen”.(5)Exposé des principes républicains de la Société des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen, s.d., p. 11-12.

Only a Republic would grant male workers (female workers were not taken into account even though they represented a third of the working class…) both the right to vote and the position they deserved: that of central political subject.

From Collective Work to Collective Ownership

The most important point of divergence between the Saint-Simonians and their allies versus the liberals was the idea that work, if properly understood, was the key to a complete reorganisation of society. According to an argument taken up and developed in the 1840s by socialists such as Louis Blanc, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, and Constantin Pecqueur, work was morally superior as an activity marked by collaboration rather than competition. Therefore, the private property system — which was immoral because it condemned workers to poverty — was to be replaced by a general association of workers. Many activists at the intersection of labour, republicanism, and socialism defended this idea, such as the typographer Jules Leroux (6)Ludovic Frobert et Michael Drolet, Jules Leroux, d’une philosophie économique barbare, Éditions Le Bord de l’eau, 2022..

Pierre Leroux’s brother Jules Leroux, also a typographer, a Saint-Simonian, and the first to have formulated the concept of socialism, was involved in the Parisian labour movement. In 1833, during a meeting of typographers in Paris, he published a brochure, “To typographic workers”. The need to establish an association to turn workers into owners of their work tools, in which he developed his concept of association. Dismissing the importance of trade divides, he defined workers as sharing a common condition, marked by submission to masters:

“Workers, whatever their profession, share the same fate. They are all in the hands of their masters, instruments of fortune; they are all subject to the vagaries of competition; they all have a miserable existence and a precarious and inadequate wage.”(7)Jules Leroux, Aux ouvriers typographes. De la nécessité de fonder une association ayant pour but de rendre les ouvriers propriétaires de leur instrument de travail, Imprimerie de L.-E. Herhan, 1833, p. 9.

This common condition was not freedom, but “isolation”: in the liberal system that he fought, “Class does not exist: there are only individuals”(8) Ibid., p. 11.. This placed workers in an immoral situation of competition when they should have been collaborating. Leroux saw worker associations as the only way for workers to emancipate themselves, by becoming collective owners of their work. Jules Leroux developed the concept of work underlying this defence of the workers’ association in other texts, and in particular in the “Work” entry of the New Encyclopedia, a large collective project directed by Pierre Leroux and Jean Reynaud(9)Vincent Bourdeau, « Un encyclopédisme républicain sous la monarchie de Juillet : Jean Reynaud (1806-1863) et l’Encyclopédie nouvelle », in Les encyclopédismes en France à l’ère des révolutions (1789-1850), Vincent Bourdeau, Jean-Luc Chappey et Julien Vincent (dir), « Les Cahiers de la MSHE », Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté, 2020.. Jules Leroux wrote most of the economic articles. In “Work”, he defined work both individually and collectively, since objects and results are “the product of the immensity of work, of the radiating waves of the infinite multitude of past, present, and future creatures”.

(10)Encyclopédie nouvelle dictionnaire philosophique, scientifique, littéraire et industriel, offrant le tableau des connaissances humaines au 19. siècle par une société de savants et de littérateurs: SAP-ZOR, Libraire de Charles Gosselin, 1842, p. 523-530..

(10)Encyclopédie nouvelle dictionnaire philosophique, scientifique, littéraire et industriel, offrant le tableau des connaissances humaines au 19. siècle par une société de savants et de littérateurs: SAP-ZOR, Libraire de Charles Gosselin, 1842, p. 523-530..

He questioned his society, founded on sole recognition of the individual’s “finished work” to the detriment of “infinite work”, that is, the collective production of all beings. Against this immoral “owner regime”, he called for a recognition of the “true nature of work” as the basis of a fundamental unity of humanity beyond the false class divides. He believed that the discovery of the true nature of labour would automatically lead to “a complete reorganisation of society” through the collective ownership of the means of production and the dissolution of the state in a society reorganised by workers’ associations. Labour thus understood could become the linchpin of society’s regeneration.

During the revolution of 1848, this conception of work— the prerogative of a working class defined as unified, unjustly excluded from politics, and exploited — would become the basis of a radical ideology: the democratic and social republic. The ideology was ephemeral but its memory shaped the history of the social movement.

Samuel Hayat, CEVIPOF

A CNRS research fellow at CEVIPOF, Samuel Hayat mainly works on political representation and on the revolutions and workers’ movements of the nineteenth century, at the intersection of the history of ideas, historical sociology, and political theory. See his publications

Notes