Making Public Policy Evaluation Accessible

14 December 2022

Are We Saturated With Organisations?

14 December 2022 The writing and rewriting of history, and its use for political purposes are in the spotlight again. But the disproportionate attention given to violence in the past – conflict and domination – has us often overlook the history of daily life, customs, and seemingly more mundane historical actors; in other words, questions of community and public welfare. Even such histories can be seized for political purposes, especially when the whole parts of these histories are obscured. Presentation by Pierre Fuller, researcher at the Center for History.

The writing and rewriting of history, and its use for political purposes are in the spotlight again. But the disproportionate attention given to violence in the past – conflict and domination – has us often overlook the history of daily life, customs, and seemingly more mundane historical actors; in other words, questions of community and public welfare. Even such histories can be seized for political purposes, especially when the whole parts of these histories are obscured. Presentation by Pierre Fuller, researcher at the Center for History.

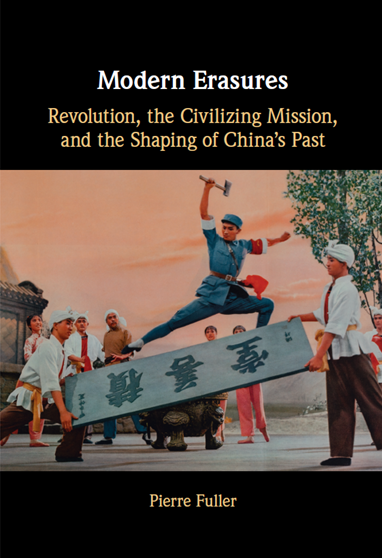

In my book Modern Erasures: Revolution, the Civilising Mission, and the Shaping of China’s Past (Cambridge University Press, 2022), I show how narratives of daily life can be conducive to the valorisation of some cultures and denigration of others. These narratives continue to structure the modern world today. I seek to highlight the extent to which many socially beneficial actions (typically performed within native communities) were left out of histories when they did not serve the so-called modernisation process.

My case study is modern China, with a major focus on the surprising overlaps and similarities between two movements that appear to be anathema to one another: the civilising mission of colonialism, on the one hand, and of communism on the other.

In both cases, state and party agents justified their interventions on the basis of sociological surveys, by identifying and classifying social actors and their (alleged) defects, and then determining solutions to remedy them. The ultimate goals of colonialism and communism, however, far apart they may seem, initially gave rise to remarkably similar discourses.

Social Studies and Colonialism

There is little doubt that native communities in the colonial world were deeply destabilised by the interventions of imperial powers and their integration into global markets. Government officials, missionaries, and the emerging social sciences purportedly studied these communities in order to capture their essence. In place of pictures of community practices over the long-term, the producers of ‘modern’ doxa were satisfied with a few snapshots of these cultures at moments of crisis, as the community fabric frayed and social obligations were jettisoned.

Vietnam is a case in point. At the beginning of the 20th century, French colonialism enterprises transformed Vietnamese subsistence farmers into landless wage earners who depended on rubber and other large plantations for their survival. As the Vietnamese were subjected to regressive taxation to fund new forms of administration and infrastructure that altered political and commercial relations at the village level, some populations benefited from new profit opportunities, while mutual support networks collapsed for others. It is in this context that French studies of the social values and associative life of the More importantly, these imperialist diagnoses were internalised by ‘Vietnamese activists and writers’ of the period, notes historian Van Nguyen-Marshall. In the 1920s, for example, they ‘portrayed philanthropy and charity as new, modern, and Western’. But the actual innovation lay elsewhere, in the new way of conceiving philanthropy, charity and civic acts as a service to the nation-state and to fellow citizens: the very ‘foundation of a modern society’(1)Van Nguyen-Marshall, “The Ethics of Benevolence in French Colonial Vietnam: A Sino-Franco-Vietnamese Cultural Borderland” en Diana Lary, ed., The Chinese State at the Borders, University of British Columbia, 2007..

In other words, native civic and humanitarian values were recast in the colonial context. They were seen as a new set of behaviours; any similarities with Confucian or Buddhist values and legacies were not taken seriously.

Interestingly, these diagnoses of colonial administrators and writers fuelled anti-colonial revolutionary ideas from the outset: native intellectuals questioned what was ‘wrong’ with their cultures and sought explanations for their submission to foreign powers, while seeking paths to national redemption. In the process, revolutionary elites first integrated colonial discourses about their so-called ‘backwardness‘ and then incorporated this vocabulary and ideology into their own programs, which they eventually deployed in political movements.

Social Erasure in the Revolutionary Era

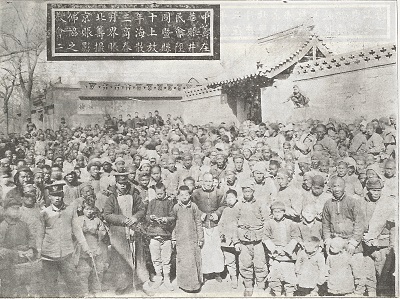

These processes may have taken their most extreme form in China. In this book, I examine how Chinese communities responded to the disasters (famines and earthquakes) that preceded the establishment of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1921. My research assumes that the communities’ response to these disasters reflects their civic and humanitarian values. Local documents of the time – especially rural annals and inscriptions on steles and tombstones – provide evidence of how victims and refugees of disaster areas were cared for within rural communities.

Spring relief distribution in Jingxing county by the Beijing Buddhist Relief Society and Shanghai Merchants Association Relief Society,’ March 1921. Jingxing xianzhi (1934). Republished in 1968 by Chengwen Publishing, Taipei.

I then look at what foreigners, and also urban Chinese intellectuals, wrote about these same events. In contrast to Vietnam, China was only semi-colonised. The literature was essentially written for a Western audience, but not by officials. Rather, it was primarily produced by the missionary movement that had been growing since the 19th century, by Western travellers, and by native elites.

Then I examine Chinese media from the 1920s and 1930s: reformist and student magazines and newspapers, civics textbooks, social surveys, and academic studies of rural life.I focus on a series of disasters that occurred in 1920, namely a famine and an earthquake that together affected tens of millions of Chinese. These events led to comments such as those by the Welsh philosopher Bertrand Russell, in China at the time: ‘Much was done by white men to relieve the famine, but very little by the Chinese, and that little vitiated by corruption’(2)Bertrand Russell, “Some Traits in the Chinese Character,” Atlantic Monthly, décembre 1921.). Catholic and Protestant missionaries and other intellectuals residing in China expressed similar ideas, including the French diplomat-poet St. John Perse and the English writer Somerset Maugham.

Then I examine Chinese media from the 1920s and 1930s: reformist and student magazines and newspapers, civics textbooks, social surveys, and academic studies of rural life. In these articles, pamphlets, and books we find a pattern: rural self-help initiatives get no mention. More precisely, the aid that held communities together, often initiated by village elders, monastic networks, or individuals not classed as ‘modernisers’, disappeared from the narratives and general discourse on Chinese life. The message was clear: village culture was incapable of meaningful civic or humanitarian action. The rural was clearly outside of the ‘modern project’. Yet local annals include many examples of native action to mitigate disaster and alleviate suffering. My book seeks to describe these two parallel perspectives – that of urban elites and colonisers, on the one hand, and of local people on the other – on Chinese rural life during the 20th century in order to shed light on much broader processes. The objective is to understand how different voices in China came to characterise the nation; how the artistic field intersected and interacted with the social sciences; and how these processes shaped some of the key premises of the Chinese revolution.

The Arrival of Mao Zedong

A quarter-century of civil war and Japanese invasion, from 1925 to 1950, coincided with Mao Zedong’s revolutionary career. During this period, Mao rose from being a propaganda officer of the Nationalist Party (Guomindang) to the head of the victorious Chinese Communist Party and founding leader of the People’s Republic of China (PRC, 1949-). This means that Maoism, as an ideological force, formed and sought to make sense of the Chinese world in the midst of social disintegration and the predations of incessant war. In other words, Maoist investigations of rural life, like most colonial studies of native cultures elsewhere in the world, were based on snapshots of communities in extreme crisis.

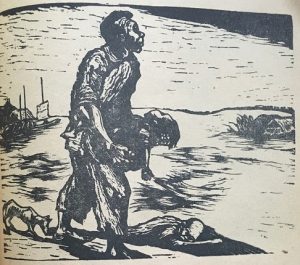

There is, however, one major difference between them: the revolutionaries’ interpretive framework was much harsher than that of the missionaries and scientists. The famine and other disastrous events of the 1920s were no longer seen as moments of inaction by the village community, but rather as reflections of predatory class relations, and of widespread exploitation and vice in rural affairs. Throughout the 1940s, recent disasters were portrayed in these terms in a variety of easily reproducible cultural productions: wood carvings, party magazines for youth, and theatrical productions by communist troupes.

https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois-165x146.jpg 165w, https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois-50x44.jpg 50w, https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois-85x75.jpg 85w, https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois.jpg 486w" sizes="(max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px" />

https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois-165x146.jpg 165w, https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois-50x44.jpg 50w, https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois-85x75.jpg 85w, https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois.jpg 486w" sizes="(max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px" />

‘He has lost all hope,’ woodcut by Ren Feng, circa 1940. Wang Renfeng, Ren Feng muke ji. Shanghai: Kaiming shudian, 1948. Beijing University Library

The terminology and policy frameworks were now Marxist, but basically carried the same message. Public welfare in rural China – and more generally the entire modernisation project – was impossible without the intervention of outside agents: missionaries, cosmopolitan liberals, and Nationalist or Communist party cadres.

History Under Xi Jinping

Europe’s attention is currently turned towards Putin’s Russia, which is trying to historically justify its invasion of Ukraine. But the state making the greatest effort to control the past is the Chinese People’s Republic (PRC). And it’s doing so with relative popular success. Under Xi Jinping, the state’s cultural ambassadors are urging the public to hunt down the agents of ‘nihilistic’ history’, that is, those who convey historical narratives that do not offer grounds for validation and celebration of the achievements and continued leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).((

举报网上历史虚无主义错误言论请到“12377” ——举报中心“涉历史虚无主义有害信息举报专区”上线.

An official announcement, created on the eve of the Chinese Communist Party’s centennial in 2021, entitled ‘To denounce online nihilism and historical falsehoods, please call ’“2377″

In the post-Mao years, under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, the party moved away from revolution to a form of performance legitimacy by ensuring economic growth, rising living standards, and, most recently, increasing military strength. In the process, the PRC has transformed into a hybrid system of socialism, capitalism, and colonialism. It is in the latter context, in Tibet and Xinjiang, that the CCP’s ‘progressive’ narratives – casting the party as liberator of people from ‘feudal’ cultures – have been most forcefully imposed.

But the recent revitalisation of the party’s control over Chinese society as a whole, centred around Xi, requires re-embracing Maoism and looking to the past to maintain a central message: If the party ceases to intervene at all levels of life, China risks regression to a past marked by social chaos. In this way, the PRC can be seen as the last vestige of the intense ‘modernisation’ endeavours of the 20th century.

Pierre Fuller is an Assistant Professor at the Sciences Po Centre for History (CHSP). His research focuses on the social history of 19th and 20th century China, the evolution of political cultures, the history of environmental crises, media and cultures, and local and transnational humanitarian discourses. See his publications.

Notes

| ↑1 | Van Nguyen-Marshall, “The Ethics of Benevolence in French Colonial Vietnam: A Sino-Franco-Vietnamese Cultural Borderland” en Diana Lary, ed., The Chinese State at the Borders, University of British Columbia, 2007. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Bertrand Russell, “Some Traits in the Chinese Character,” Atlantic Monthly, décembre 1921.). Catholic and Protestant missionaries and other intellectuals residing in China expressed similar ideas, including the French diplomat-poet St. John Perse and the English writer Somerset Maugham. Then I examine Chinese media from the 1920s and 1930s: reformist and student magazines and newspapers, civics textbooks, social surveys, and academic studies of rural life. In these articles, pamphlets, and books we find a pattern: rural self-help initiatives get no mention. More precisely, the aid that held communities together, often initiated by village elders, monastic networks, or individuals not classed as ‘modernisers’, disappeared from the narratives and general discourse on Chinese life. The message was clear: village culture was incapable of meaningful civic or humanitarian action. The rural was clearly outside of the ‘modern project’. Yet local annals include many examples of native action to mitigate disaster and alleviate suffering. My book seeks to describe these two parallel perspectives – that of urban elites and colonisers, on the one hand, and of local people on the other – on Chinese rural life during the 20th century in order to shed light on much broader processes. The objective is to understand how different voices in China came to characterise the nation; how the artistic field intersected and interacted with the social sciences; and how these processes shaped some of the key premises of the Chinese revolution. The Arrival of Mao ZedongA quarter-century of civil war and Japanese invasion, from 1925 to 1950, coincided with Mao Zedong’s revolutionary career. During this period, Mao rose from being a propaganda officer of the Nationalist Party (Guomindang) to the head of the victorious Chinese Communist Party and founding leader of the People’s Republic of China (PRC, 1949-). This means that Maoism, as an ideological force, formed and sought to make sense of the Chinese world in the midst of social disintegration and the predations of incessant war. In other words, Maoist investigations of rural life, like most colonial studies of native cultures elsewhere in the world, were based on snapshots of communities in extreme crisis.  https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois-165x146.jpg 165w, https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois-50x44.jpg 50w, https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois-85x75.jpg 85w, https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois.jpg 486w" sizes="(max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px" /> https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois-165x146.jpg 165w, https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois-50x44.jpg 50w, https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois-85x75.jpg 85w, https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ren-Feng-gravure-en-bois.jpg 486w" sizes="(max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px" />‘He has lost all hope,’ woodcut by Ren Feng, circa 1940. Wang Renfeng, Ren Feng muke ji. Shanghai: Kaiming shudian, 1948. Beijing University Library The terminology and policy frameworks were now Marxist, but basically carried the same message. Public welfare in rural China – and more generally the entire modernisation project – was impossible without the intervention of outside agents: missionaries, cosmopolitan liberals, and Nationalist or Communist party cadres. History Under Xi JinpingEurope’s attention is currently turned towards Putin’s Russia, which is trying to historically justify its invasion of Ukraine. But the state making the greatest effort to control the past is the Chinese People’s Republic (PRC). And it’s doing so with relative popular success. Under Xi Jinping, the state’s cultural ambassadors are urging the public to hunt down the agents of ‘nihilistic’ history’, that is, those who convey historical narratives that do not offer grounds for validation and celebration of the achievements and continued leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).(( |