You Better Move On!

22 October 2018

Frugal city: a 3rd way between “business as usual” and decline?

25 October 2018 When preparing to become a lawyer * in France, it is necessary to choose fairly rapidly the branch to specialise in: private or public law. Once the election is made, the opportunities to learn about the branch that was not chosen thin down. For Sciences Po Law School permanent professors Christophe Jamin and Fabrice Melleray, this separation is unfortunate. This is what they demonstrate in their latest work Droit civil et droit administratif. Dialogue(s) sur un modèle doctrinal (Civil law and administrative law. Dialogue(s) on a doctrinal model. Dalloz, april 2018), which was granted the Prix du livre juridique 2018. Interview.

When preparing to become a lawyer * in France, it is necessary to choose fairly rapidly the branch to specialise in: private or public law. Once the election is made, the opportunities to learn about the branch that was not chosen thin down. For Sciences Po Law School permanent professors Christophe Jamin and Fabrice Melleray, this separation is unfortunate. This is what they demonstrate in their latest work Droit civil et droit administratif. Dialogue(s) sur un modèle doctrinal (Civil law and administrative law. Dialogue(s) on a doctrinal model. Dalloz, april 2018), which was granted the Prix du livre juridique 2018. Interview.

Nota bene : Throughout the interview, « lawyer » is used as the English translation of juriste, to refer to someone who is educated in the law.

Your book aims at proving that specialists in civil law (private law’s main branch) and in administrative law (public law’s main branch) do not know each other well, while they have very much to share.

Christophe Jamin: yes, we are convinced that they are not that different, and that they share more than they believe, which has been the case for a long time. It is in fact the central theme of the book, whose subtitle – Dialogue(s) sur un modèle doctrinal – alludes to a single intellectual framework. This hypothesis served as a thread to our discussions. We consider this framework as doctrinal to the extent that it is based on the predominance of legal technique, implying in particular a certain form of exclusion from the legal discourse of what is political and of the social sciences.

You have chosen the epistolary form to develop and convey your reflexions. It is a real Unidentified Flying Object in legal literature!

C.J: Yes it is unusual, and it has been a real literary and intellectual experience. This format has given us much more liberty than we would have had, had we written an essay or a textbook. Having more specially students in mind, but also an audience that is not necessarily familiar with certain legal questions, we attempted to reproduce in the liveliest possible way the substance of the legal discussions and controversies, without uniquely addressing their technical aspects. As such, we are convinced that law remains another way to talk about politics, with arguments and reasoning frameworks belonging to lawyers only, and which are sometimes difficult to access.

It is not until the end of the 19th century that public law has gained a place within the law faculties’ curricula, which were until then dominated by private law. This intrusion was ill-perceived by the civilistes. What was at stake?

Fabrice Melleray: The civilistes are indeed in a quasi-hegemonic situation until the end of the 19th century. Public law’s development (to a large extent a development in administrative law), which is not without connection to the republican ideology, ![Conseil d'Etat. Crédits photos : Jastrow [Public domain], de Wikimedia Commons Conseil d'Etat. Crédits photos : Jastrow [Public domain], de Wikimedia Commons](https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/570px-Conseil_dEtat_Paris_close-up_2007_03_10-285x300.jpg) provoked concern among the civilistes. The most informed among them are conscious of the advantages of the Conseil d’État’s case law, which forms the basis of administrative law, compared to the aging Code civil. And public law is first of all attractive to students… But most civilistes seek to guarantee their pre-eminence and the central role of civil law. Yet to this aim, they must renew the methods. On their end, publicistes defend their discipline’s specificity, its originality and its autonomy compared to private law.

provoked concern among the civilistes. The most informed among them are conscious of the advantages of the Conseil d’État’s case law, which forms the basis of administrative law, compared to the aging Code civil. And public law is first of all attractive to students… But most civilistes seek to guarantee their pre-eminence and the central role of civil law. Yet to this aim, they must renew the methods. On their end, publicistes defend their discipline’s specificity, its originality and its autonomy compared to private law.

In civil law, the main reference has for long been the Code civil, developed under Napoleon, and which is hence a dated, somewhat frozen piece, while administrative law is created along the way by the Conseil d’État. What does this imply for these two branches?

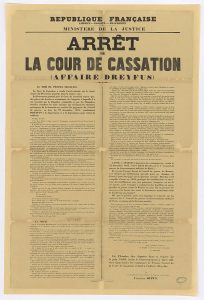

C.J.: One of the challenges facing the civilistes in the first years of the 20th century lies in exiting an intellectual domain shaped by the Code civil. At this point, and especially during the inter-war period, civil law does not quite equate Code civil anymore. Civilistes at the time further argue that the Code civil’s reading, which is mostly exegetical, is a constraint that does not allow addressing anymore the demands of a society that has substantially changed since 1804. Since it responds to the concrete questions of society, the case law has thus become increasingly important to them and this, to a certain degree, brings them closer to the publicistes. ![Cour de Cassation. Crédits photo : Par myself [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) ou CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], de Wikimedia Commons Cour de Cassation. Crédits photo : Par myself [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) ou CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], de Wikimedia Commons](https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/397px-Courdecassation-quai-horloge-199x300.jpg) Nevertheless the Cour de cassation (which rules on civil law) does not play such a hegemonic role as the Conseil d’État’s (which rules on administrative law) so that the importance acquired by the case law does not take civilistes away from their attraction to the Code civil.

Nevertheless the Cour de cassation (which rules on civil law) does not play such a hegemonic role as the Conseil d’État’s (which rules on administrative law) so that the importance acquired by the case law does not take civilistes away from their attraction to the Code civil.

Does the difference between these two branches of law not also stem from the fact that their specialists have received a different education?

F.M: There is no fundamental difference in education between university specialists in private and public law, even though specialisation is done far too early and is encouraged by a conception of the teaching of law that is overly technique-centred. The key original feature of public law, and more precisely of administrative law, lies in the existence of an organic doctrine, which holds the primary role. In other words, the members of the Conseil d’État are the ones commenting on and systematising their own case law. And contrary to their Cour de cassation counterparts, the members of the Conseil d’État, with some rare exceptions, have not been educated in law faculties.

And for what regards their relations to power?

F.M: Obviously the relation to power of the Conseil d’État members can only be different to that of faculty members. The relation to power is equally different between administrative judges and publicistes faculty members on the one hand, and between judiciary judges and privatistes faculty members on the other.

You also show that these two branches of law experience similar influences throughout the 20th century.

F.M : Although breaking history into particular periods is clearly somewhat artificial, it appeared to us that three distinct time periods could be identified in both branches of law. The first time period, from the end of the 19th century to the 1930s is that of the construction of the doctrinal model. The second, extending probably until the 1970s, is that of the rolling out of this model, marked by some crises, in particular the passionate debate on the progressive influence of public law in the domains until then reserved to private law. At that time, many privatistes had voiced concerns regarding the development of public interventionism in the economic sphere. Finally, we identify a third time period, currently visible, which is that of the possible reconsideration of the model. The evolutions of the sources and the general directions of French law – consider in particular the place now held by European law and the place increasingly taken by fundamental rights – have inevitably tried this model and affect civil and administrative law in largely comparable proportions. The French doctrinal model assimilated law with a system that today tends to make it resemble a kaleidoscope!

Much more than law is to be found in your book. Your refer to politics, sociology, and it is a meticulous historical account… Is this an illustration of one of the Law School’s major ambitions consisting in tying more narrowly law with other social sciences?

F.M: Yes, one of the Law School’s ambitions is not to be satisfied with an overly dogmatic approach, which has notably resulted in a form of isolation of lawyers and in their exclusion from intellectual debates. A lawyer cannot only be a technique virtuoso who would talk uniquely to his or her pairs. Taking a step back from what strongly resembles a French way of practicing the law, like we have done in this book, contributes to this attempt at going beyond the dogmatic approach.

Christophe Jamin, university professor and Dean of the Sciences Po Law School, focuses his research on economic law, the law of obligations and contract law. He also studies the history of legal thinking. Fabrice Melleray, university professor at the Sciences Po Law School, is an expert in administrative law and in its multiple branches: contract law, property law, dispute resolution, law of the civil service and public services law.