The Political Consequences of Technological Change

6 May 2019

Strong links between social inequalities and political activism

6 May 2019by Caterina Froio

Assistant Professor at the Center for European Studies and Comparative Politics

The online presence of far-right organizations, activists, and figures, and the dissemination of their ideas through social networks, have become bogeymen for most political commentators. While researchers agree that social networks allow these political entrepreneurs to disseminate their ideas, it is still unclear how these exchanges are produced and what their content is.

In order to answer these questions, I conducted research* with Bharath Ganesh (Oxford Internet Institute) and presented the findings in the journal European Societies: The transnationalisation of far-right discourse on Twitter.

We studied various far-right formations, that is, political parties and social movements that are characterized by their ethnocentrism and authoritarian vision of society, in line with Cas Mudde’s definition presented in the book Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

We proceeded by examining Twitter exchanges between these formations, their activists, and their leaders in four Western European countries: France, Italy, Germany, and the United Kingdom. The idea was to identify – despite the national specificities – common dissemination networks, and define their characteristics, shared ideas, and promoters. To this end we studied the transnational circulations of their digital discourses.

Towards a transnational far right?

Brothers in arms: Young right-wing populist leaders from Italy, Belgium, France, Austria, Great Britain and Germany. Crédits réservés : DW/K.A Schlotz

On the basis of the general observation that the Internet is a perfect refuge for the political expression of the far right (because of easy access and low costs), and in the absence of research on the issue of social networks, we sought to understand if and how Twitter can allow these political communities to disseminate their ideas beyond national boundaries.

Indeed, much of the research on historical or contemporary far rights has shown that their characteristic ethno-centered discourses are not incompatible with their willingness to expand internationally or to cooperate with foreign organizations. We defined the trans-nationalization of the far right as a focus on a same theme. In other words, the far right is transnational when linked groups belonging to more than one country share certain themes and develop a shared interpretation of social reality. In the Twitter universe, this trans-nationalization should translate into the establishment of transnational exchanges on common themes.

Identifying the actors

This work built on a novel database covering far-right digital audiences in France, Italy, Germany, and the United Kingdom. These countries significantly differ with regard to the importance of far-right parties at the polls and the intensity of street mobilization.

For each country, an initial sample including around ten Twitter accounts was developed. Following the purposive sampling technique we selected Twitter accounts according to their importance and to their diversity (Parties, movements, and figures). We then collected the re-tweets from these accounts (meant to demonstrate approval of the re-tweeted discourse) over 2016 and 2017, in order to obtain a systematic sample of significant re-tweeters from the four studied countries.

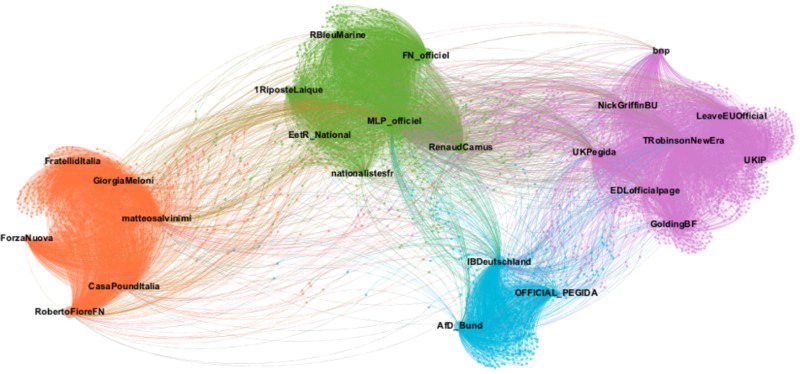

Thanks to network analysis, we were able to detect transnational links between far-right organizations on the basis of re-tweets by far right users from one country to another.

Identifying the type of shared content

We then coded the re-tweets according to their content, which we compared to contents re-tweeted within national communities. Finally, by isolating the effects of each variable, we quantified the probability that some specific issues (like the economy, immigration, etc.) or the discourses of some formations and/or leaders in particular would be re-tweeted to other countries. Finally, we analyzed the content to describe the interpretative frameworks accompanying these exchanges. The findings presented in the graph below are based on 6,454 re-tweeters identified as having re-tweeted a far right message more than once. Of the 55,983 re-tweets that we identified, only 1,617, or barely 3%, crossed borders.

The network of far-right re-tweets. From left to right: Italy, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom Source: Froio Ganesh (2018) European Societies

National preference as the only federal theme

Anti-Moschee-Demonstration der als verfassungsfeindlich eingestuften Bürgerbewegung pro Köln (2008) par Jasper Goslicki – Eigenes Werk. CC BY-SA 3.0

Findings also show that a tweet has a 47% chance of becoming transnational if it is issued by a political party (a formation participating in the elections), but only 25% if it is issued by a simple movement (such as the English Defense League). Of the transnational re-tweets, two themes are especially widespread: the economy and immigration – two themes where we identified a 30% chance of being re-tweeted transnationally.

More specifically, two interpretative frameworks appear to be transnational. First, Islamophobia, which casts Muslims as both a cultural and security threat to the West, drawing on fears of invasion and ethnic replacement, and on a vision of Islam as a monolithic, fundamentalist, and ideological religion. The far right thus paradoxically positions itself as a defender of individual freedoms (like those of women or LGBTQ people) that are supposedly central to national identity. Second, economic nativism, which values the economy as a means to serve the interests of the nation and of its nationals, thus abstracting itself from the classical State-market divide.

The limits of transnationalism on Twitter

We ultimately observed a limitation in the transnational dimension of the far right on Twitter, and thus rejected the idea of a “dark international”. The ideological variety characterizing this ideological family is apparently too significant to be overcome, even virtually, except on consensual themes like Islam and economic nativism. This can be observed, for example, in the tweets targeting political representatives that are not able to overcome the national boundaries of each far-right formation, even though the theme may be shared by all of them, because the denunciation of elites is achieved through specifically national references.

In sum, this research challenges the preconception of the existence of a “dark international”, at least on Twitter, based on a major observation. On Twitter, far right ideas are disseminated transnationally, but these exchanges remain limited to very few themes that are nonetheless central to the far right’s ideology. This points to the need to focus not only on xenophobia on the internet, but also on the feeling of economic insecurity and on how the latter can be reconciled with a demand for both State intervention in the economy, and a “laisser-faire” approach. Future research on other forms of transnationalism and social networks covering longer periods will be needed to more specifically inform us of these trends.

* This research was conducted as part of a VoxPol research project funded by the European Union. It is based on an academic network that studies the importance, contours, functions, and impacts of violent political extremism online, and the resulting responses. Learn more (eng)

Caterina Froio is Assistant Professor in political science/e-politics at the Centre for European Studies and Comparative Politics (CEE). Her research focuses on political parties, far right extremism, digitalization, and forms of political participation. Learn more

- Froio, Caterina, 2017 – Nous et les Autres. L’altérité sur les sites web des extrêmes droites en France in Réseaux