Are Finance and Democracy Irreconcilable?

18 December 2019

Cogito 8 – Governing Finance

18 December 2019

Big Stock Exchange. Crédits image : Gorodenkoff, Shutterstock

All projects need financing. The State, businesses and households can either finance projects with their own funds or loans. While loans used to be in the hands of private lenders and major banks, financial markets cover most of them today. Bringing together numerous players in a connected global system, financial markets have become the nervous system of our economies. Like an information network on project viability, it transmits data from one corner of the world to another without care for the impact of financial flows on daily life. Furthermore, the system can seize up and become grounds for irrational behavior and speculation, while delivering considerable profits to actors at the heart of the financial sector.

The public has a dim view of finance, as was fully exposed by the 2008 financial crisis. Bearing this in mind, during his presidential campaign François Hollande declared in his Bourget speech of 22 January 2012 that his “true enemy […] is the financial world”. Is the financial sector free from political control?  What do we know about the dynamics and balance of power between the financial industry and politics? Ten years after the 2008 financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis of 2010, how can one assess the governance of the financial sector and its impact on our societies?

What do we know about the dynamics and balance of power between the financial industry and politics? Ten years after the 2008 financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis of 2010, how can one assess the governance of the financial sector and its impact on our societies?

Taking a comparative and long-term view, this issue’s contributions shed light on the tensions between globalized finance, politics, and societies. Since the end of the Bretton Woods system and its barriers on capital flows, this tension has become a particular challenge for our contemporary democracies as voter demands can clash with the preferences of the markets that public and private actors need. At the same time, regulation is evolving in an attempt to better control finance and bestow it with societal objectives. An analysis of this evolution reveals that politics has not capitulated to markets, but rather is trying to regulate them, sometimes in a very interventionist way, and sometimes very indecisively. This ambiguity has granted finance a major role in our lives, with a growing volatility of capital flows and a notable impact on wealth distribution.

Finance and democracy

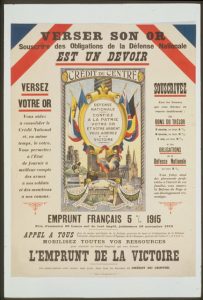

In a historical overview, Nicolas Delalande shows that public funding has been a democratic challenge for centuries. In the aftermath of WWII, “regulated capitalism” marked by capital controls constituted a notable exception. Since the 1970s the financialization of the economy and of societies has amplified tensions between market imperatives and citizen demands.

But as Pamfili Antipa and Quoc-Anh Do argue in their article – Legislating to make money – democratic institutions do not necessarily protect the public interest. Their analysis of the implementation of monetary policy in Great Britain at the beginning of the 19th century reveals this. Following in-depth research, they show that private interests have considerably skewed political decision-making.

Politics also remained important during historical moments that are portrayed as market takeovers. By piecing together an oral history of the sovereign debt crisis that hit Latin America in the 1980s, Jérôme Sgard breaks from analyses that emphasize the role of markets in its resolution. He underscores the emergence of multilateral coordination via the International Monetary Fund, and the dominating role of States in the organization of banks’ private initiatives.

State versus market

That being said, it is hard to strike a balance between political imperatives and market dynamics. Politics reflect national objectives, while market regulation requires coordination at higher levels, meaning that the regulatory framework can result from a long and tortuous process. This is the story that Pierre François tells in his work on the regulation of the European insurance market . By analyzing the harmonization of the notion of risk in the European “Solvability 2” directive, he shows that the regulation of insurance activities required many exceptions in each State, contrary to its initial goal of integrating the European market.

Finance and society

Market financing involves many constraints for both businesses and households. For businesses listed on the stock exchange, the formalism of their activities report and of their financial communication has been the subject of many studies. In his article dedicated to entrepreneurial finance, Martin Guiraudeau shows that this formalisation is even an issue for new businesses which must convince investors specialized in high-risk projects. It would therefore be erroneous to believe that young entrepreneurs seduce investors through interpersonal relations, as some authors suggest.

Within households, daily life has not been spared by financialization. Jeanne Lazarus analyzes how the State tries to address citizens’ exposure to financial markets, their volatility, and economic risks. In her article, Household money, a policy issue, she shows that the French government has implemented public and collective protection instruments. These not only encompass the regulation of banking and financial activities, but also the financial education of citizens, preparing them for participation in the market.

Finally, the impact of finance on the evolution of socio-economic inequalities is at the heart of public indignation. In his article – Less finance, fewer inequalities? Ten years after the crisis – Olivier Godechot focuses on recent data to assess whether the financial sector’s contribution to increasing inequalities is as great as it was in the pre-crisis years. Indeed, one might expect a more regulated financial sector to have less impact on inequalities today. The research shows that the evolution significantly differs from one country to the next. While the joint growth of finance and inequalities is declining or reversing in Canada, Sweden, and Germany, it remains significant elsewhere. As demonstrated for the insurance sector, political intervention remains visibly shaped by national contexts, even as finance has become one of the most globalized sectors.

These contributions highlight the great significance of the regulation of the financial system, appearing in all of its complexity. As a provider of indispensable capital, it creates important social and political challenges that States must address. This is a tall order. While States are crucial to guiding finance, their control is fragmented, and some activities escape their authority. For our societies, the increasing significance of finance in daily life remains a major transformation of our time.

Cornelia Woll, Sciences Po/CEE, MaxPo et LIEPP