Gender Inequalities in Higher Education

18 May 2020

Marital Separations and the (Non-) Emancipation of Women

18 May 2020by Hélène Le Bail, CERI*

The migration of women through marriage is an old phenomenon, which renewed in the 1990s with international mobility. On the basis of collective research(1)Hélène Le Bail, Marylène Lieber, Gwenola Ricordeau, dossier “Migrations par les mariage et intimités transnationales” [Migrations through marriage and transnational intimacy], Cahiers du Genre, 2018, I present two key dimensions of this phenomenon. The first is a continuum between migration for work and migration for marriage, both of which are linked to the provision of care. The second relates to the tensions between analytical frameworks emphasizing agency, with women owning their migration, and those casting the migration as exploitation of women’s bodies and labor.

Japanese Picture Brides at Angel Island in 1919. © Public domain

Female migration yesterday and today

Marriage between people living in different countries dates back to colonial history, which is full of examples of women sent to be married to settlers or to more or less forcefully imported male labor, which was often excluded from the local marriage market. Thus, from the Japanese pictures brides married to Japanese immigrant workers in the United States at the beginning of the 20th century to current marriages between “second generation” people and spouses from their parents’ countries of origin, marriage accompanies the history of migration.

In addition, many societies have practices of moving for marriage related to traditions of requiring people to find a spouse outside the local group’s village (exogamy) and to settle in the village of the husband’s father (patri-virilocality). Thus, marriage migration has long played an important role in women’s mobility. It has been, and sometimes remains, one of the few socially acceptable ways for women to leave their hometown.

Thus the mobility of women for marriage has long corresponded either to endogamous dynamics at the international level (marriages with colonists or within diasporas), or to exogamous dynamics at the local level. What distinguishes the phenomenon of marriage migration today is that it combines long distances and exogamy in a globalised marriage market.

Marriage and migration intermediaries

The development of international marriages is partly attributable to the rise of international matchmaking platforms. These cross-border marriages involving geographical distance between future spouses require to some extent the involvement of an intermediary. In the case of expert tour operators (Romance Tours and Marriage Tours), meetings are entirely staged and organized by mediators.

Internet cafe in Kampala © Arne Hoel / World Bank

International marriage agencies, some of which are online, offer various services depending on their client’s abilities (command of a foreign language and digital tools, comfort with travelling alone for first meetings, etc.) and the complexity of administrative procedures. Similarly, on social networks, in some cases people operate independently, while in others they are assisted by an intermediary with knowledge of the websites and the ropes of communication (such as the “monitors” of cybercafés in West Africa). Finally, mediation is sometimes simply provided by a relative or a person known by word-of-mouth who took the same migration path a few years earlier.

The geography of marriage migration

The phenomenon of marriage migration is developing in all the main migration channels: from Eastern to Western Europe, from Latin America to North America, from Southeast to Northeast Asia, and from Northern and Sub-Saharan Africa to Europe. The mobility is often marked by the legacy of colonial history, but other channels are largely attributable to the emergence of new economies and the development of virtual social networks. Our special issue for the Cahiers du Genre carefully sought to gather research conducted in diverse historical and socioeconomic contexts. It includes the case of Asian wives in Japan, North African men in Canada, Russian women in China, Mexican and Colombian women in the United States, African women in France, etc. However, of all these migratory routes, East Asia is the most affected area. The development of marriage migration translated into a rapid increase in international marriages in the 1990s and 2000s. They accounted for a significant share of marriages celebrated in Taiwan (27.4% in 2004), South Korea (13.6% in 2005), and Japan (6.1% in 2006). These figures are high considering that the foreign population share is under 2% in these countries. European countries and the United States are also affected by this phenomenon. Given their restrictive migration policies, marriage is a facilitated means of entry despite scrutiny over possible marriages of convenience

Family migration or work migration?

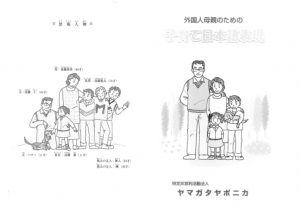

Japanese manual for immigrant wives: reproducing the model family

Research on the globalization of care and of reproductive work shows that the feminization of migratory flows is often motivated by the growing need for labor in sectors of activity considered to be feminine. These needs are attributable to population ageing, the generalization of women’s employment, the rapid increase in celibacy, and the revival of salaried domestic labor. Just like care assistants, nannies, and domestic workers, foreign wives are contributing to the feminization of migration considering that, even in migration, reproductive work is being carried out, be it paid or not.

In countries like Taiwan and Singapore, which opened their doors to foreign workers in the care and domestic sector long ago, cross-border marriages are also common. Researchers have underscored that in countries with small welfare states marriage migration is an alternative for families who cannot afford paid care services. It becomes strategic for older men or for the families of people with disabilities to choose marriage as a means of providing care services within families. Meanwhile, Japan, the region’s rich country, has the most restrictive migration policy in the care sector, and even more so in the domestic work sector. But even there, in 1997 Nicola Piper(2)Piper Nicola – “International Marriage in Japan: ‘Race’ and ‘Gender’ Perspectives”. Gender, Place & Culture, 1997 published one of the first articles casting marriage migration in terms of work. The author describes these marriages as an inexpensive way for men to obtain domestic and sexual services in exchange for economic and legal resources (residence status). Japan is the most prosperous country in the region.

Fresnoza-Flot, A. and G. Ricordeau (eds.). International marriages and marital citizenship. Southeast Asian women on the move. 2017, Routledge

This choice is sometimes supported by local communities, or even by the government. In Japan, for example, the increase in cross-border marriages is linked to initiatives to combat depopulation. Beginning in the 1970s, a large number of rural localities started using funds earmarked for combating depopulation to finance programs to promote marriages among their residents: recruitment of marriage counselors, financial support for wedding ceremonies, the organization of meetings at parties, sports outings, trips to which women from neighboring towns are invited. In this context, some localities prioritized cross-border marriages. Korean authorities also set up programs to promote marriages in the 2000s. The big difference between Japan and Korea is that the latter legislated at the national level (international marriage support law for rural singles).

Thus research on marriage migration informs and enriches research on the links between the “care crisis” and female migration beyond paid work, and beyond the framework of global cities.

Migrant wives: commodification of the body or agency?

In the 1980s, early studies of migrant wives focused on the commodification of women. This research highlighted the unequal nature of these unions because most marriage migration flowed from poorer countries to wealthier countries, corresponding to the hierarchy of spaces in terms of prosperity. Moreover, the flows related to colonial histories and revived exotic and erotic imaginaries and racist stereotypes.

Cupidmedia matchmaking agency web screen capture

More recently, research has focused less on the actual marriages than on the women (less often men) who enter them, placing the agency of women at the heart of the reflection. The research has highlighted women’s deployment of marriage and migration strategies, including in international meetings. International marriage is then analyzed as a means of individual emancipation: the leitmotiv in stories of migrant women is the search for a marital modernity that they cannot find in their country of origin.

This tension between the commodification and agency of women runs throughout the research on marriage migration and echoes debates over prostitution and sex work, with which they are often assimilated. But whether the focus is on migration or on marriage, the defining aspect of this phenomenon is precisely that it lies at the intersection of migration and marriage dynamics.

Hélène Le Bail, a CNRS researcher at the Center for International Studies (CERI), focuses on Chinese migration in Japan and in France, as well as migration policies from a comparative perspective. She especially focuses on feminine migratory paths (marriage, reproductive work, and sex work), as well as mobilization and collective action questions.

Translated from French by Carolyn Avery

- CHUANG, Ya-Han, Hélène LE BAIL. “How marginality leads to inclusion: insights from mobilizations of Chinese female migrants in Paris“, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 2020

- LE BAIL, Hélène, Marylène LIEBER et Gwenola RICORDEAU, eds. “Migrations par le mariage et intimités transnationales” Cahiers du Genre, 2018

- LE BAIL, Hélène. “Cross-Border Marriages as a Side Door for Paid and Unpaid Migrant Workers: The Case of Marriage Migration between China and Japan” Critical Asian Studies, 2017

- LE BAIL, Hélène. “Un Projet migratoire sur deux générations. Les épouses migrants chinoises et leurs enfants au Japon“, Hommes et Migrations, 2016

- LE BAIL, Hélène. “Mobilisation de femmes chinoises migrantes se prostituant à Paris. De l’invisibilité à l’action collective” Genre, sexualité & société, 2015

Notes

| ↑1 | Hélène Le Bail, Marylène Lieber, Gwenola Ricordeau, dossier “Migrations par les mariage et intimités transnationales” [Migrations through marriage and transnational intimacy], Cahiers du Genre, 2018 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Piper Nicola – “International Marriage in Japan: ‘Race’ and ‘Gender’ Perspectives”. Gender, Place & Culture, 1997 |