This Peculiar Epidemic is a Happiness Disease…

3 July 2020

Artificial Intelligence: What Revolution Are We Talking About?

3 July 2020by Roberto Galbiati, Department of economics*

© MikeDotta, Shutterstock

Many democratically elected governments around the world are probably wondering how voters will respond to the policies they implemented to face the COVID-19 crise. Some will expect voters’ support to go up on ideological basis, others will anticipate a response driven by the immediately observable consequences of the policies. Health policies are not unique, the researcher that wants to predict their consequences faces the same obstacles of predicting the electoral impact of other kind of policies: we do not observe empirical counterfactuals.

In order to properly understand how and whether voters respond to government’s policies, the ideal experiment would require the government to randomly manipulate the content of a policy and then this random manipulation mapping into different outcomes. For example, to properly assess the voters’ response to a tax increase or cut by the central government, it would be necessary to observe a random variation of its effects across lower levels of government, for instance municipalities. Or, given an emergency health policy, it would be necessary to observe locally random variation in its intensity. Such a local random variation would allow to identify the causal effect of the policy outcome on voters’ electoral behavior conditioning on the ideological preferences of voters on these types of policies. In other words, causal responses of voters to policies can be correctly assessed only if we observe variations in the effects of the policy that are independent both from the voters’ and the government’s characteristics.

Criminal Justice: an Important Influence on Voter Behaviour?

© Fresnel, Shutterstock

In a recent paper Drago, Galbiati and Sobbrio(1)Drago, F., Galbiati, R. and Sobbrio F. – « The Political Cost of Being Soft on Crime: Evidence from a Natural Experiment », Journal of the European Economic Association, 2019., we address this issue by focusing on criminal justice. In this work, we focus on criminal justice because crime is perceived as a crucial social issue in most Western countries. In the Eurobarometer survey, for instance, crime ranks among the top five most important problems in several European countries(2)Mastrorocco, Nicola and Luigi Minale « News Media and Crime Perceptions: Evidence from a Natural Experiment », Journal of Public Economics, 2018.. Accordingly, there is a widespread belief that criminal justice policies have a significant impact on voting behavior. Indeed, elected officials seem to believe that being soft on crime does not pay off(3)Levitt, Steven D. – « Using Electoral Cycles in Police Hiring to Estimate the Effect of Police on Crime », American Economic Review, 1997..

Nevertheless, despite the importance of this issue for potential voters and the observed behavior of politicians, existing studies on the link between crime control policies and voters’ behavior are mostly correlational and provide mixed evidence(4)Hall, Melinda Gann « State Supreme Courts in American Democracy: Probing the Myths of Judicial Reform », American Political Science Association, 2001 / Krieger, Steven A. « Do Tough on Crime Politicians Win More Elections–An Empirical Analysis of California State Legislators from 1992 to 2000 », Creighton Law Review, 2011..

The Italian case study

The study exploits a natural experiment in Italy that allows us to have a proper counterfactual to evaluate the voters’ response to the consequences of the policy keeping their ideology and the impact of the policy on ideological stands constant.

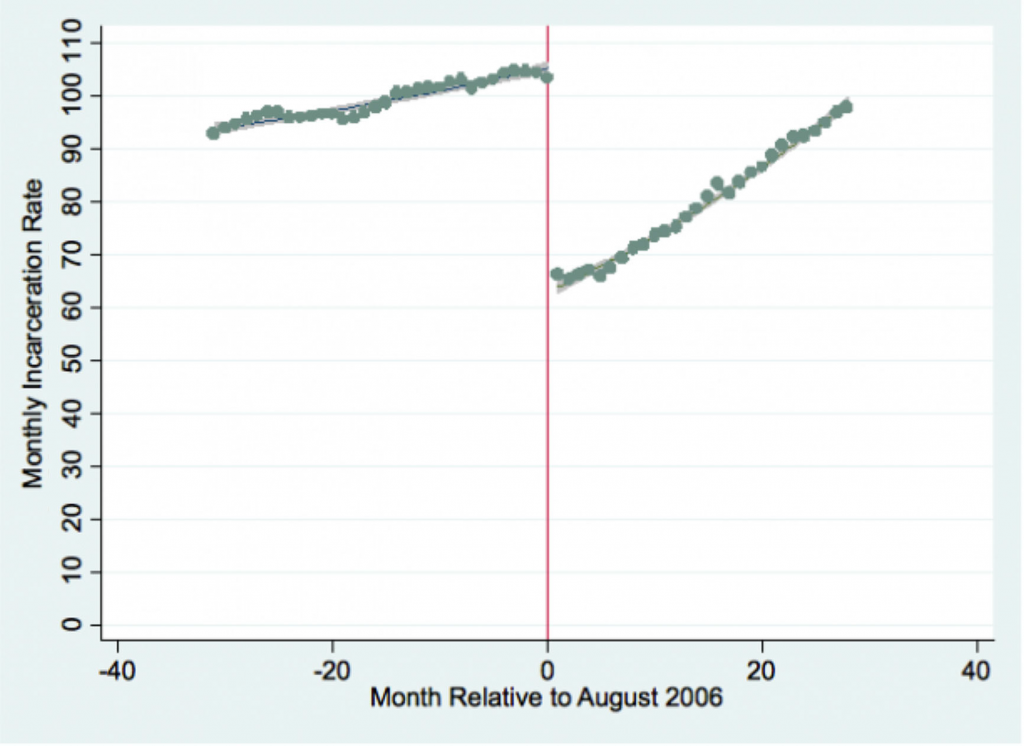

In July 2006, the Italian government implemented an (unanticipated) collective pardon due to a dramatic overcrowding in prisons at that time. As a result, a subset of the prisoners with less than 36 months of residual sentence were released and about the 30% of inmates in Italian prisons are release on August 1st 2006 (Figure below).

Figure 1 : Incarceration rate before and after the collective pardon

NOTE: The figure illustrates the variation in the incarceration rate (i.e., per 100,000 people) in Italy before and after the collective pardon bill.

The design of the policy was such that released prisoners who would recidivate within a five-year period, would be charged an additional sentence equal to their residual sentence at the time of their release. This created an incentive to refrain from re-offending for pardoned individuals that increases in the length of the residual sentence.

© frankie’s, Shutterstock

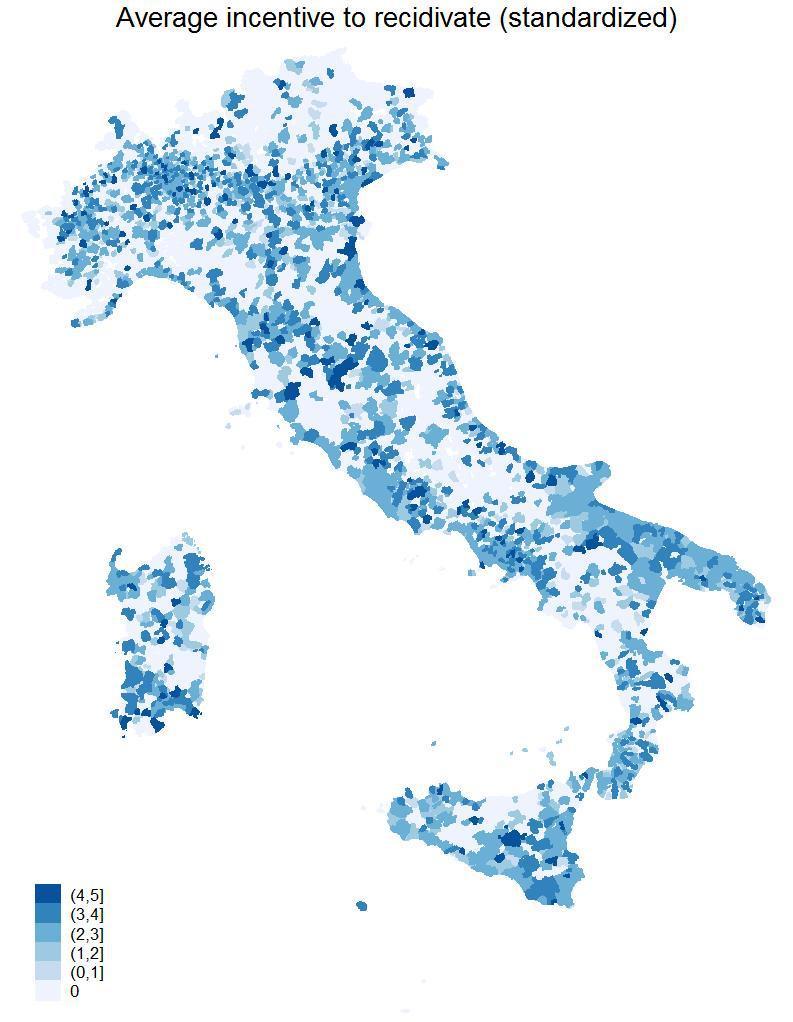

Such an incentive, as shown in previous research(5)Drago, Francesco, Roberto Galbiati, and Pietro Vertova – « The Deterrent Effects of Prison: Evidence from a Natural Experiment » , Journal of Political Economy, 2009. turns out to be exogenously distributed across released prisoners. Two identical individuals that entered the first time in prison with a sentence of 50 months, at the time of pardon in August 2006 may have two different residual sentences, and thus a different incentive to recidivate, because they entered prison in different periods. Since the date of entry into prison is plausibly exogenous to future criminal behavior, the Italian collective pardon provides a unique opportunity to evaluate voters’ response to the realised effects (recidivism rates) of the pardon. (Figure below).

Figure 2. Distribution of the Incentive to Recidivate over Italian Municipalities

The figure illustrates the geographical distribution of the (standardised) average incentive to recidivate of pardoned individuals at the municipal level. A one unit increase corresponds to a one standard deviation increase in the incentive to recidivate (i.e., around 8.2 months less of residual sentence). This means that if you consider two municipalities with a difference of 1 in this scale the difference in the incentive to re-offend in the two communes is about 8.2 months of expected sentence.

© to the People All Power, CC BY-NC 2.0

Hence, by using the variation in the incentive to recidivate across municipalities we can assess to what extent voters respond to the effects of the crime control policy by holding all the rest equal. In our study we first show that, as expected, municipalities where pardoned individuals had a higher incentive to recidivate experienced a higher recidivism. Then, we document that individuals do take into account the observed effects of the policy in their voting decisions. In municipalities with a higher incentive to recidivate voters “punished” the political coalition who put forward such pardon (center-left) in the first post-pardon parliamentary elections. The effect is quantitatively relevant. An increase of recidivism of 15.9% led to a 3.06% increase in the margin of victory of the center-right coalition in the post-pardon national elections (2008) relative to the last election before the pardon (2006).

This shows that worse observable effects of the policy at the local level, imply worse electoral outcomes for politicians responsible for such policy. What are the mechanisms that drive this result? We show that where the incentive to recidivate is higher, newspapers report more crime news on pardoned individual recidivating. Moreover, voters update their beliefs about the competence of the incumbent coalition to deal with crime. Importantly, a higher incentive to recidivate was not associated with individuals being more likely to perceive crime as the most important issue in Italy or in their city. This suggests that votes correctly associated the pardon with the recidivism of pardoned inmates and not with crime in general.

General Lessons Beyond Crime Control Policies

The capacity of voters to assess policies and reward of punish politicians accordingly is crucial for the health of political institutions. A few existing studies cast some doubts on ability by providing evidence of voters punishing/rewarding incumbent politicians in the presence of events that are orthogonal to government’s policies, such as shark attacks(6)Achen, C H, and L M Bartels – « Blind retrospection: Electoral responses to drought, flu, and shark attacks », Working Paper, 2004., performance of local sport teams or lottery winnings. On the contrary, voters respond to the observed effects of a public policy (both in terms of beliefs and behavior) in a way that is consistent with standard voting economic models of electoral accountability Or, at least, they seem to be able to do so as long as they observe the effects of a policy, either through direct observation and word of mouth or, as we document, via news media.

In a historical moment in which ideological polarisation seem to be one of the main drivers of policies and voters’ responses, these findings seem relevant for the political debate in Europe and abroad. The effects of policies matter over and beyond ideology since voter hold politicians accountable for the realised effects of public policies as long as it is possible to identify who is responsible for such policies.

This project was supported by the ANR and the French government under the Investments for the Future program LabEx LIEPP (ANR-11-LABX-0091, ANR-11-IDEX-0005-02) and IdEx Université de Paris (ANR-18-IDEX-0001).

Roberto Galbiati is a CNRS Professor (DR) in the Department of Economics at Sciences Po. His research interests are law and economics, political economy and applied microeconomics. He has studied extensively how laws and individual motivations affect cooperative behavior and compliance, the effects of law enforcement on illegal behavior and the emergence and stability of legal and political institutions.

Notes