The 1980s Debt Crisis: the Players and the Archives

18 December 2019

Finance: A Political and Social Challenge

18 December 2019

Graphic via Seth Tobocman from Understanding by The Crash Howl Arts Collective. CC BY 2.0

A historical overview

Finance is now considered to be the main driver of growing inequality. At the same time, governments are being pilloried for their inability to fight its excesses. This has had disastrous political consequences: challenges to democracy and rising extremism. Nicolas Delalande‘s look to the past shows that tensions between States, people, and finance have a long history.

Over a decade ago, the 2007-2008 crisis shook the global economic system. Beyond its effects on people’s living standards and wellbeing, its political consequences are a new focus. The disrepute of traditional parties, the rise of far-right populist movements, and social revolts all point to the cracking legitimacy of democratic regimes.

A deep rift between democracy and finance

One of the most cited structural reasons for democratic distrust is the inability of governments to meet their populations’ expectations with regard to purchasing power, employment, and inequality reduction. According to the German sociologist Wolfgang Streeck (1)Wolfgang Streeck – Du temps acheté : La crise sans cesse ajournée du capitalisme démocratique , Gallimard, 2014, this powerlessness stems from a growing and irreparable rift between democracy and financial capitalism, with voters and markets placing two contradictory types of demands on governments, which have fallen into virtually total dependence on the latter, thus fueling the former’s anger. How to believe in the virtues of democracy if international investors can, by buying and selling securities, undo choices legitimately made through the ballot box, as seems to have recently been the case in Greece and other Eurozone countries?

First critiques under the Ancien Régime

Le Doyen des fermiers généraux porté par quatre commis aux barrières conduit par les troupes de son corps faisant route vers le néant. Domaine Public

So-called “financiers” under the Ancien Régime never had good press. 17th and 18th-century monarchies depended on them to borrow funds and collect taxes. Kings could certainly repudiate their debts and dismiss the financiers, but they had to negotiate with them to tap into precious revenue without which no war could be sustained. On the eve of the French Revolution, “collector generals”, among the richest men in the kingdom, elicited such popular ire that the smuggler Louis Mandrin, openly at war with Customs agents in the 1750s, became a hero of the people, who were revolted by the injustice of the levies.

An oligarchy of rentiers

In the United Kingdom, despite the “financial revolution” at the end of the 17th century, leading to the creation of the Bank of England (1694) and the rise of the City, the financial community also came under fire. In the 1760s and 1770s, a radical critique cast the landed and moneyed elites’ oligarchic privileges as detrimental to the people and workers. In a selective suffrage system in the hands of two major parties – the Whigs and the Tories – Parliament was failing in its primary mission to represent the interests of the English nation. Radicals calling for the democratization of the British political system saw the public debt, which was colossal at the beginning of the 19th century (over 200% of British annual income after the Napoleonic Wars) as a mechanism of extortion whereby rentiers (government bonds were the most common financial securities at the time) enriched themselves on the backs of taxpayers, who were heavily taxed through consumption taxes.

Finance versus the Nation-State?

![James de Rothschild (1792-1868). [Public domain]](https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2004/11/James_de_Rothschild-255x300.jpg)

James de Rothschild (1792-1868). Public domain

In France, at the end of the 19th century, denunciation of financial capitalism was deeply rooted in socialist circles and could sometimes veer into anti-Semitism, as seen in many pamphlets published at the time against “financial feudalism”. Examples include The Jews, kings of the epoch. The history of financial feudalism by Alphonse Toussenel (1845) and The Kings of the Republic by Auguste Chirac (1883). Meanwhile, rightwing adversaries of the Republic lambasted the racketeering of a regime supposedly in the hands of Freemasons, Jews, and “international finance”.

All rentiers!

![Action provisoire de la Compagnie Universelle du canal interocéanique de Panamà. 1888. Ferdinand de Lesseps [Public domain]](https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2004/11/ActionPanama-300x244.jpg)

Action provisoire de la Compagnie Universelle du canal interocéanique de Panamà. 1888. Ferdinand de Lesseps [Public domain]

The Republic adopted this model: the consent of the people had to be expressed both in the ballot box and in their wallets. At the beginning of the 20th century, proponents of this model were convinced that the success of the Republic rested on the democratization of both (male) suffrage and the stock exchange. Several million savers held shares of the public debt, even though it was very unevenly distributed. Ideologically, this diffusion of rents supposedly confirmed the existence of true “financial democracy”. Money invested abroad, in government securities, and in mining and railway bonds, also served the purposes of colonial imperialism, which had spread to all four corners of the globe.

A democracy of investors

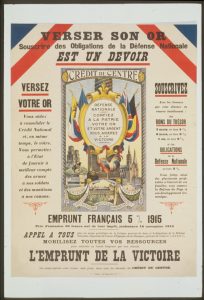

L’Emprunt de la Victoire, 1920. Source : Library of Congress. Crédits : Public Domain

With the two World Wars, this phenomenon of expanding the circle of public debt holders became the norm in many countries. Citizens were expected not only to support the war politically and militarily, but also economically and financially. In the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Russia, the purchase of government bonds was presented as a new patriotic duty – a sign of unfailing loyalty and confidence in the future. When voluntary commitment was no longer enough, coercion and social pressure were deployed. As historian Julia Ott (2)Julia Ott , When Wall Street Met Main Street: The Quest for an Investors’ Democracy , Harvard University Press, 2011 has shown, the American federal state’s legitimation of the link between public debt and citizenship was then used in the 1920s by Wall Street to justify the social role of private finance as conducive to the fulfillment of individual freedoms and dreams of prosperity. Then the 1929 crisis triggered a series of bankruptcies, revealing the illusory nature of this promise, the weight of which was not equally shouldered.

The need for regulation

Crowd at New York’s American Union Bank during a bank run early in the Great Depression. Public Domain

From the 1930s to the 1940s, government intervention to regulate financial activities became a political and economic imperative. This fragile and temporary balance, directly linked to the effects of the wars and the Great Depression, gave rise to the regulated or “embedded” capitalism of the 1950s and 1960s that accompanied the expansion of democracy in the wake of the Cold War and the decline of empires. But over time, this episode increasingly appeared to be an exception in the long history of capitalism. The financialization of the economy and societies that began in the 1970s, as sociologists and economists have thoroughly analyzed, reactivated the growing rift between finance and democracy. This is the scientific and political challenge we face in a world that has become more vulnerable as resources are depleted and inequality grows.

Nicolas Delalande, Associate Professor and researcher at Sciences Po’s Center for History, focuses on the history of the State, inequalities, and solidarity in Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries. He has published La Lutte et l’Entraide. L’âge des solidarités ouvrières [Struggles and assistance. The age of wokrer solidarity] (Seuil, 2019), Les Batailles de l'impôt. Consentement et résistances de 1789 à nos jours [Tax battles. Consent and resistance from 1789 to today] (Seuil, 2011 and new edition, 2014) and edited, with Nicolas Barreyre, A World of Public Debts. A Political History (Palgrave MacMillan, to be published in 2020).

Notes

| ↑1 | Wolfgang Streeck – Du temps acheté : La crise sans cesse ajournée du capitalisme démocratique , Gallimard, 2014 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Julia Ott , When Wall Street Met Main Street: The Quest for an Investors’ Democracy , Harvard University Press, 2011 |