![]() A group of researchers at the Center for the Sociology of Organisations has recently published a book entitled: The society of organisations (Presses de Sciences Po, May 2022). Drawing on a range of topics, the authors explore the causes and consequences of the proliferation of organisations, and their impact on our lives. They draw links between organising and other processes: globalisation, the digital revolution, the growing range of measurement tools, and the omnipresence of the law. Finally, they assess the effects of organisations on such topics as inequalities, democratic erosion, and global warming. Presentation by Olivier Borraz, CNRS research director at the CSO.

A group of researchers at the Center for the Sociology of Organisations has recently published a book entitled: The society of organisations (Presses de Sciences Po, May 2022). Drawing on a range of topics, the authors explore the causes and consequences of the proliferation of organisations, and their impact on our lives. They draw links between organising and other processes: globalisation, the digital revolution, the growing range of measurement tools, and the omnipresence of the law. Finally, they assess the effects of organisations on such topics as inequalities, democratic erosion, and global warming. Presentation by Olivier Borraz, CNRS research director at the CSO.

The book starts with a simple, almost banal observation: we live in a society teeming with organisations. What do we mean by this? Simply the fact that no dimension of our lives escapes organisations: whether it is the formal organisations to which we belong or with which we interact on a daily basis, or the numerous organising processes set in standards, procedures, and algorithms that frame our behaviour, determine our preferences, and constrain our decisions. Our lives are more organized than ever. This stands in contrast with the fact that until recently, many facets of our lives were still based on informal practices and structures. Our private spheres were still loosely formalised spaces: they were framed by customs, oral rules, and traditions that were not subject to extensive control by external entities. They were internalised and transmitted from generation to generation without being organized in impersonal and general norms.

Today, most of our daily actions unfold in a dense network of organised structures and processes. This does not mean that we have abandoned all freedom of choice, but it does imply that our choices are largely embedded in forms that structure our preferences and options. Accordingly, addressing the threats currently facing our societies requires understanding the implications of this society of organisations.

Multiple Dynamics

This organisational proliferation is attributable to several drivers.

– The first driver is legal, with the rise of legal professions and forms of legalisation that are proliferating in many areas of economic, political, and social life. The risks of legal action prompt many organisations to increasingly formalise their activities both internally and in relation to their customers, suppliers, partners, etc., in order to protect their reputation.

– The second driver is technological. Behind descriptions of a world supposedly flat and flexible due to digital technology, we see the emergence of firms of unprecedented size (the infamous GAFA), the reproduction of power dynamics in virtual systems (through control and access to data, for example), and a whole process of codification, normalisation, and even surveillance of our behaviour via the algorithms running on our smartphones and computers and transforming these behaviours into data benefiting a limited number of actors.

– The third driver pertains to professions. Organisations and professions have long been conceived in opposition. But it has become clear over the past few decades that the two not only coexist: they even feed off each other. Some professions have become formidable purveyors of organized forms, allowing them both to establish their hold over their field of competence and to subordinate other professions to their authority. Moreover, these organized forms rarely match the boundaries of formal organisations, but rather tend towards crosscutting expansion both nationally and internationally.

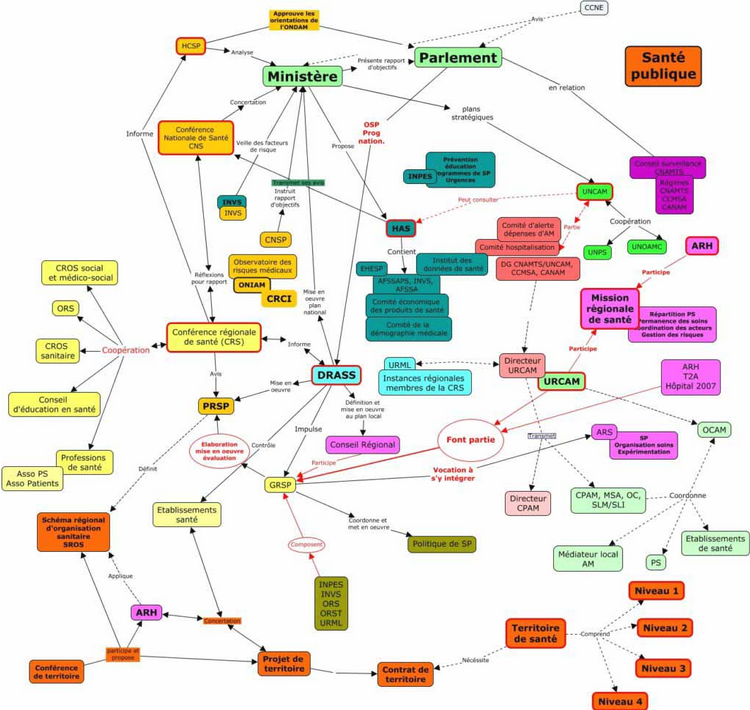

– Finally, the fourth driver is what the book refers to as a neo-bureaucratic vicious circle. This refers to the reflex, when faced with a new problem, to immediately consider its resolution through an organisational creation. The new organisation thus created is often added to a long list of existing organisations, causing coordination problems that can only be solved with yet another organisation. The book draws on healthcare, higher education, and research fields to illustrate this vicious circle, which consists of thinking of the solution to public policy coordination and inefficiency solely in terms of organisations and organising.

Organisations Versus Individual Responsibilities?

Many scholars insist that the fight against inequalities, global warming, and public health problems is primarily a matter of individual behaviour. In other words, by reading bedtime stories to our children, by biking instead of driving, and by taking the stairs instead of the elevator, we can individually contribute to a collective benefit. Governments act on these behaviours using more or less intrusive tools: from coercion to taxation, and from nudges to education, in order to encourage (the preferred approach today) or force individuals to adopt the ‘right’ behaviours that will reduce CO2 production, educational inequalities, and obesity.

However, the original error of these approaches in behavioural economics, psychology, or neuroscience, is that they overlook the fact that our behaviours are not solely dictated by our individual preferences or macro-social factors. Rather, they are first and foremost part and parcel of organized forms that are at the origin of the inequality, global warming, and public health problems that they are trying to solve. Here are a few examples.

The organisation of work is a formidable source of inequalities, both at a global level and within each organisation: be it economic, social, gender or ethnic inequalities, the organisations in which we evolve or with which we interact are the crucibles of these inequalities. Organisations contribute to inequalities in the way they distribute work, organise interactions, and manage careers and remuneration.

The rise of populism is not just related to class issues or loss of trust in elites: it is a direct result of choices made in land use planning, the location of economic activities, urbanisation, and the provision of services. These are all political decisions that largely determine our choices of where to live, our relationships with others, and our identities.

Finally, the fight against global warming should not be strategised at the individual level, with recommendations that we lower hour home temperature, bike to work, or consume local products. This completely eschews the problems of housing conditions, available transportation, and the organisation of food distribution. Organisations are proliferating in all these sectors.

In short, it is time to reintroduce organisations into research and public action. Not as simple formal structures, but as places where almost all of the daily interactions take place. Not as simple legal entities, but as spaces where individuals interact, cooperate, struggle, negotiate, and make decisions. Not as simple vectors of inequalities, global warming, and public health problems, but as their causes..

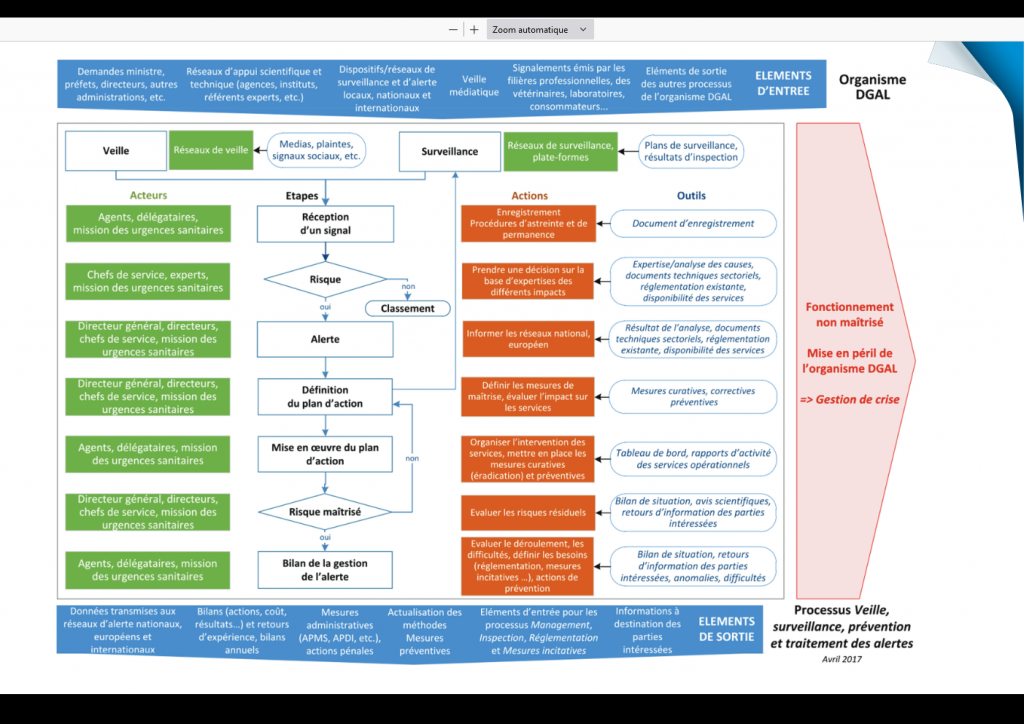

Data sheet on the “Watch – Surveillance – Prevention and Processing of alerts” process of the DGAL organization, resulting from the project group associating agents from decentralized services and central administration. Ministry of Agriculture – General Directorate for Food. Department of governance and international affairs in the areas of health and food. Sub-directorate for the management of resources and cross-cutting actions. Quality management and control coordination office.

That being said, our membership and interactions with multiple organisations should be examined from all angles. While overlapping memberships can be a source of contradictions, inconsistencies, and tensions, they are not necessarily deleterious! It is their alignment that is sometimes worrisome: should we always adopt the same behaviours, formulate the same preferences, and make decisions that are invariably consistent with one another? In other words, organisational proliferation also has virtues, some of which are attributable to its chaotic nature.

The Virtues of Spontaneity

It is no longer possible to conceive of collective problems other than in organisational terms. But what the Covid-19 pandemic revealed is precisely the fact that French society was able to demonstrate innovation and adaptation at the margins or outside of existing organized forms. Individuals and groups were able to break away from the rules and procedures to frame their behaviour and interactions, and thereby find or rediscover more traditional forms of solidarity based on mutual aid and cooperation. In this respect, the crisis underscored the limitations of exclusively organisational approaches. On the contrary, it showed the importance of finding informality within or between organisations.

The society of organisations addresses these various questions. It makes an observation and sheds light on the mechanisms, but also outlines pathways for research and action. The book is the result of a collective effort involving all 28 CSO researchers. Most of them do not identify to the sociology of organisations as their field of specialisation. But from their disciplines (sociology, history, political science), their theoretical frameworks, their topics, and their methodological approaches, they all come across organisations in their fields of research and share the same observation of organisational saturation. The book gave them the opportunity to discuss organisations in their fields (work and employment, professions, law, knowledge and expertise, the state and public action, economics, etc.) and thus renew the sociology of organisations. In all immodesty, the book demonstrates that it is not possible to approach sociological phenomena without considering the role of organisations. Work, democracy, inequalities, climate change, and the digital revolution are all, and perhaps primarily, organised phenomena.

CNRS research director Olivier Borraz heads the Center for the Sociology of Organizations. His research focuses on risk governance and crisis preparedness.