Evaluating Environmental Policies

8 July 2021

Measuring French Pessimism

8 July 2021By Carlo Barone, Observatoire sociologique du changement

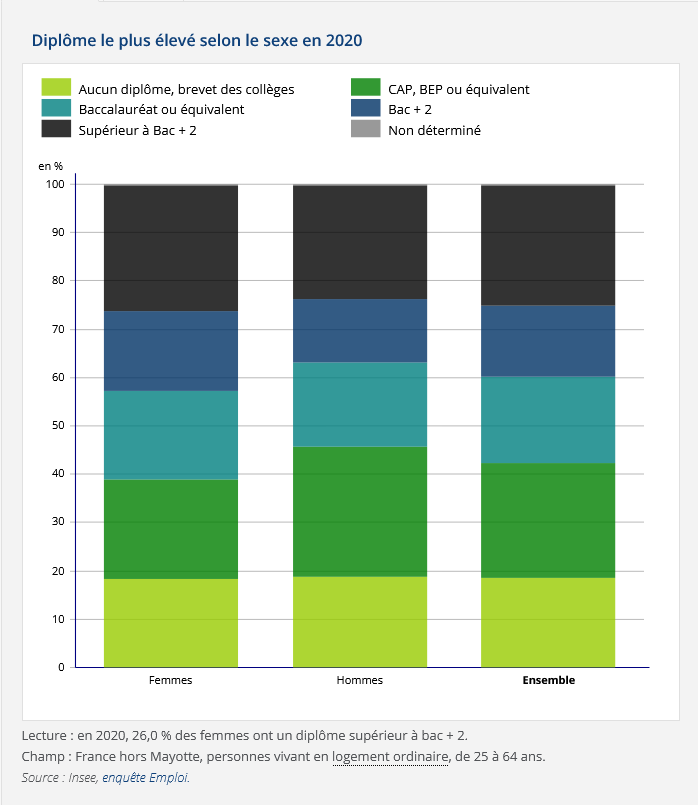

Women now outperform men in education: their rates of upper secondary and tertiary attainment are significantly higher in virtually all OECD countries(1)In France, 26% of women, compared to 23% of men, have a baccalaureate degree +3 in 2020. Source INSEE.. Thanks to these advancements, gender gaps in earnings and other labour market outcomes have substantially narrowed in recent decades and women currently access graduate jobs as much as men.

However, when we look at the field of study of graduation, we find that women are still underrepresented in some of the most rewarding tertiary fields, such as engineering and ICT, while they’re overrepresented in some fields with below-average earnings, such as arts and humanities. More importantly, gender segregation in higher education (GSHE) is highly resistant to change, even in recent cohorts displaying dramatic increases in the educational and labour market participation of women. Since persisting GSHE is one of the most important drivers of the gender wage gap, understanding how and when GSHE is produced is of utmost importance in order to develop effective policies to erase it. So, how is GSHE generated? Unfortunately, we know very little about its drivers. To be sure, several explanatory hypotheses have been proposed, but the empirical evidence is scant, and largely confined to the US.

However, when we look at the field of study of graduation, we find that women are still underrepresented in some of the most rewarding tertiary fields, such as engineering and ICT, while they’re overrepresented in some fields with below-average earnings, such as arts and humanities. More importantly, gender segregation in higher education (GSHE) is highly resistant to change, even in recent cohorts displaying dramatic increases in the educational and labour market participation of women. Since persisting GSHE is one of the most important drivers of the gender wage gap, understanding how and when GSHE is produced is of utmost importance in order to develop effective policies to erase it. So, how is GSHE generated? Unfortunately, we know very little about its drivers. To be sure, several explanatory hypotheses have been proposed, but the empirical evidence is scant, and largely confined to the US.

We have a long list of potential explanatory candidates, but we know little about their relative weight. In the following section, we quickly sketch them and discuss whether they shed light on this phenomenon. In order to provide this answer, we have exploited a rich, large-scale, longitudinal survey carried out in France by the statistical office (DEPP) of the Ministry of Education that followed a cohort of students from entry into secondary education to higher education completion, collecting data from students, teachers, parents and administrative sources(2)Estelle Herbaut, Carlo Barone, “Explaining gender segregation in higher education: longitudinal evidence on the French case”, British Journal of Sociology of Education, 2021..

Seven Explanations for Gender Segregation in Higher Education

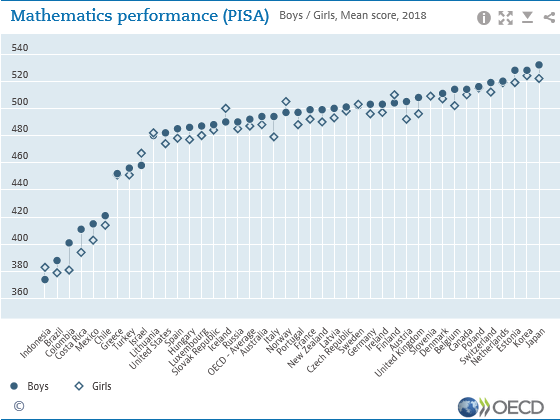

The most common argument to explain GSHE is that, since girls have lower math and science skills, they chose math-intensive fields such as engineering less often. However, international surveys such as PISA (OECD Programme for International Student Assessment) and TIMSS report (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study) that in most OECD countries gender gaps in math are small and that science gaps are even smaller (or they even favour girls). Still, boys are overrepresented in the upper tail of the distribution of math skills, which could enhance their access to STEM fields. Is that the case?

Our results indicate that boys’ modest advantage in math plays no explanatory role for GSHE. Besides, we may note that girls are currently overrepresented in some scientific fields, such as biology and medicine, and even in the math-intensive field par excellence, that is math, a pattern that is arguably related to their interest in teaching.

Skills could matter the other way around, however. Girls perform much better than boys in language skills and humanistic subjects. Hence, they could be tempted to choose fields where they’re strong performers. This second explanation thus stresses the strengths of girls, rather than their weaknesses. But our study indicates that this explanation also fails to account for GSHE. All in all, skill gaps between girls and boys matter little.

Less pronounced ambitions?

Maybe girls are less career-oriented than boys: they attach less importance to earnings or to the prestige of their future occupations? Once more, our study found that gender differences in these respects are small and that they play an even smaller role for GSHE. In the younger generations, the career orientation of girls and boys isn’t very different. Hence, the argument that girls aren’t ambitious enough to take scientific fields turns out to be as weak as the argument that they’re not skilled enough to complete them. Importantly, this conclusion confirms the results of a previous study that we carried out in Italy using a similar analytical approach, thus suggesting that this conclusion isn’t specific to the French case(3)Carlo Barone and Giulia Assirelli – “Gender Segregation in Higher Education: An Empirical Test of Seven Explanations”, Higher Education, 2020..

External influences difficult to measure

The next two explanations that we consider referring to the gender stereotypes of teachers and of parents. We don’t put much emphasis on these results because, differently from our high-quality measures for skills and for career orientations, the measures available in our data aren’t strong. More generally, measuring adult stereotypes with survey data is challenging. This said, the explanatory power of these measures looks limited and we know from other studies that, at least for teachers, there are reasons to believe that they play a limited major role in fostering GSHE.

The significant part of oblivious stereotypes

- A predilection for interactive trades

So, what’s behind the different choices of girls and boys after high school graduation? One factor that plays an important role relates to the gendered preferences for specific occupations. While girls attach importance to earnings and job stability as much as boys, they’re particularly attracted to occupations having a care orientation, such as psychologists, teachers and social workers.

© Shutterstock

Boys are more attracted to jobs having a technical orientation. We could say that girls are more motivated to interact with people to help them, while boys are more attracted to the manipulation of objects and of spatial relations. If we think about the toys that girls and boys are given since their early childhood, we see how these expressive elements of work preferences disclose the persisting power of gender stereotypes and socialisation practices.

- A Gendered Choice in the Studied Disciplines

Curricular choices in high school are the other key explanatory factor. Gender matters a lot for the choice of elective subjects and of specialities in general tracks (bac scientifique, économique et social, littéraire) as well as in technological or vocational tracks, where for instance girls dominate in design, health and social service curricula, while boys are overrepresented in industry-oriented curricula. Gender stereotypes probably also affect these gendered expressive preferences for different curricula. As a result, girls and boys like different subjects and thus take different paths in high school, which then constrain the set of accessible fields of study. Interestingly, the above-mentioned study of the Italian case reports the same patterns: curricular choices, subject preferences and expressive occupational preferences account for a large part of GSHE.

These analyses suggest that students adopt a twofold filter to select their field of study: they consider those fields that they can complete and that they like to attend. Curricular choices and subject preferences probably matter for both: students develop skills in different domains and thus are more or less able to succeed in different fields, and they learn to appreciate different topics thus developing an interest in different disciplines. The preferences for specific occupations act as a reinforcement mechanism that can further channel girls and boys into different tertiary paths.

So, what can be done to reduce GSHE?

Public Policy: The Need for Better Information on Job Opportunities

A first observation is that the two above-mentioned filters don’t often lead to the preference for a single field of study.

Actually, we know from previous research that many students are still highly undecided among two or three fields even a few weeks before they take their final decision. Moreover, students are often poorly informed about the very different labour market prospects of tertiary fields. This explains why information interventions about labour market returns to tertiary fields have the potential to reduce GSHE. This is confirmed by two recent randomised information experiments where students of the experimental group received detailed data on earnings, unemployment risks and other labour market indicators of tertiary fields: girls of the experimental group (but not boys) moved toward more rewarding and less gender-segregated fields (such as psychology, art or language studs), thus reducing significantly to the overall level of GSHE(4)Carlo Barone, Antonio Schizzerotto, Giovanni Abbiati, and Gianluca Argentin – “Information Barriers, Social Inequality, and Plans for Higher Education: Evidence from a Field Experiment”, European Sociological Review, 2017Barone et al., 2017..

Moreover, our analyses indicate that gender segregation in secondary and in tertiary paths are strongly intertwined. This means that we must intervene as early as possible, in particular when students make their first curricular choices in the early years of high school, and even earlier in lower secondary education. However, most programs to reduce GSHE are proposed at the end of high school. Most often, they consist of short interventions exposing students to gender-atypical role models (e.g. the female scientist) and activities (e.g. a science lab targeting female students) to counter gender stereotypes. Unfortunately, a recent review of these interventions reports that they’re largely ineffective. This is quite unsurprising, as they arrive too late in the process of formation of preferences for specific disciplines and occupations. Starting earlier and with more prolonged interventions is essential in order to influence career plans.

Overall, our suggestion for policy-makers is that the best strategy to reduce GSHE probably relies on the complementarity between these two types of interventions: programmes focusing on student preferences should start as early as possible and rather take a long-term perspective, while light-touch information interventions targeting undecided students are probably the best option when the final choice approaches.

Carlo Barone is a professor of sociology focusing on education and social stratification, researcher at the Sociological Observatory of Change (OSC). He’s affiliated with the Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Evaluation of Public Policies (LIEPP) heading the Educational Policy’s track. He usually uses international databases to disclose the drivers of social mobility and segregation, throughout long life, from a comparative perspective. He implements experimental methods and on-field interventions, as is currently with family reading helps in Parisian primary schools.

Notes

| ↑1 | In France, 26% of women, compared to 23% of men, have a baccalaureate degree +3 in 2020. Source INSEE. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Estelle Herbaut, Carlo Barone, “Explaining gender segregation in higher education: longitudinal evidence on the French case”, British Journal of Sociology of Education, 2021. |

| ↑3 | Carlo Barone and Giulia Assirelli – “Gender Segregation in Higher Education: An Empirical Test of Seven Explanations”, Higher Education, 2020. |

| ↑4 | Carlo Barone, Antonio Schizzerotto, Giovanni Abbiati, and Gianluca Argentin – “Information Barriers, Social Inequality, and Plans for Higher Education: Evidence from a Field Experiment”, European Sociological Review, 2017Barone et al., 2017. |