The history of international trade in data

25 October 2018

The Politics of Symbols: the French Government’s Response to the 2015 Terrorist Attacks

27 October 2018Economics present a surprising empirical regularity expressed by what is called the gravity equation: in a given year, over at least the past century for which precise data exists, the value of exports has been approximately proportional to the size of countries, and inversely proportional to the geographical

distance separating them. In other words, two countries 500 km apart trade twice as much as two countries 1,000 km apart, all other things being equal.

Globalization doesn’t change anything?

The role played by geographical distance has remained a mystery since the Dutch economist Jan Tinbergen discovered the gravity equation in 1962. It runs counter the impression we have when we observe the power and global presence of increasingly global brands like Apple, Heineken, and Toyota. Yet the data confirm it: distance has the same impact on international trade activity today as it did in 1880. The world is not becoming flat!

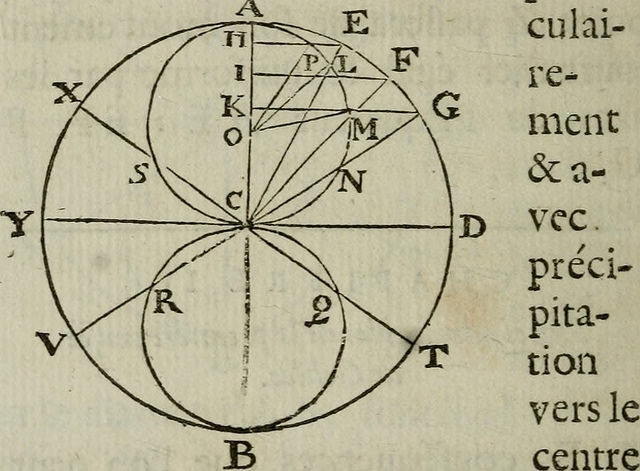

This empirical consistency is all the more intriguing that it is precise and stable. It is one of the empirical regularities in economics that most closely resembles regularities observed in physics.

The world is different depending on whether one is big or small!

Thomas Chaney, a professor in Sciences Po’s department of economics, offers a simple explanation for this apparent mystery. In his article “The Gravity Equation in International Trade: An Explanation”, published in the prestigious “The Journal of Political Economy”, he observes that geographical distance has a negligible impact on the largest firms, which are also the most visible ones. He notes on the contrary that distance is of considerable importance for small companies. The main reason for this is that direct relationships with clients and suppliers are essential for them, and maintaining these relationships over long distances is cost-prohibitive.

The national distribution of firm size as the key to unlocking the mystery

The national distribution of firm size as the key to unlocking the mystery

From this observation, Thomas Chaney infers that the effect of geographical distance on trade flows between countries depends on the relative importance – the distribution – of small and large exporting firms in a given country. And he mathematically demonstrates that depending on the distribution of the size of exporters, aggregate exports remain inversely proportional to the distance to their destination. In other words, even if all the firms end up escaping gravity as they grow, so long as the distribution of the size of exporting firms in a country remains stable, dividing the distance of its exports by two will continue to double their value. He is therefore suggesting that the key to understanding the mystery of the precise role of distance in international trade lies in the distribution of the size of firms.

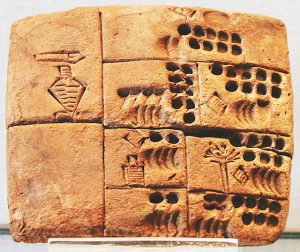

And 4,000 years ago?

And 4,000 years ago?

Moreover, in a recent study on trade during the Bronze Age (“Trade, Merchants, and the Lost Cities of the Bronze Age”), Thomas Chaney and his coauthors show that 4,000 years ago geographical distance had double the impact on trade that it has today: moving from 1,000 to 500 km multiplied trade flows by 4, versus the current 2 today. A possible explanation is that during the Bronze Age there were no coalitions of merchants as important as today’s big businesses. It would be a challenging but worthy hypothesis to test!