Measuring the Quality of Care, a European Overview

12 December 2021

Conspiracy Theories and Epidemics: What Ebola Can Teach Us

12 December 2021By Renaud Crespin, Centre for the Sociology of Organisations

Diego Maradona, 2010. © Alexandr Mysyakin, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia

While doping in the professional sports world regularly makes the headlines in the media, the idea that these practices might have spread to all professions and economic sectors remains taboo. Since the times when Doctor Villermé denounced ‘drunkenness’ as ‘the greatest scourge of the working classes’ in 1840(1)Villermé, L. R. (1986). Tableau de l’état physique et moral des ouvriers employés dans les manufactures de coton, de laine et de soie (2 volumes, 1840). Réédition sous le titre Tableaux de l’état physique et moral des salariés en France. Paris : La Découverte., the world of work has changed; the uses and features of psychoactive substances (PS) have diversified. We worked with a group of researchers (2)These surveys were mainly carried out with Dominique Lhuilier and Gladys Lutz as part of the PREVDROG-Pro research project funded by Mildeca and INCA (2011-2014) then continued in the SURIPI project funded by ANSES (2016-2021).to try to understand the purpose of psychoactive substance use, focusing on the meaning that professionals attribute to PS. This research led us to dismantle prejudices and misconceptions about workplace drug uses in order to better grasp their complexity. It also spurred reflections on current prevention and care.

When Statistics Fall Short

The first challenge is to assess usage. Like other illicit or socially condemned activities, workplace drug use is a practice that both employees and employers most often seek to hide. However, figures and statistics on the extent of drug use and its associated risks are in the public domain(3)Crespin, R. (2015). Le sens des mesures. Usages et circulation des chiffres dans la définition du problème public des drogues au travail. Psychotropes. – for example, in studies estimating illicit substance use among professionals.

However, although these studies assess the distribution of drug use by socio-professional categories, most of the available statistics do not indicate whether or not respondents use drugs in the workplace. We chose to focus on the overlooked substance use at work using the so-called snowball method. The technique consists of contacting a small population of individuals, and then expanding the sample by asking initial participants to identify others. This technique quickly enabled us to interview around 40 people using PS in connection with their profession. A first finding from our surveys is the ‘trivialisation’ of substance use at work.

© Shutterstock

Jettisoning Conventional Wisdom

We also show that the use of psychotropic substances, which are diversifying, does not just fall within the remit of performance research. Nor can it be reduced to the idealised image of the chronic alcoholic haunting many companies. Between these two extremes lies a plethora of uses that need to be analysed in relation to contemporary work transformations. This is needed not only to rethink the complex relationships between work and substances, but also to question prevention policies and actions. Some stereotypes carry the idea that occupational PS uses are a localised and private problem that vulnerable people bring into the workplace. They thus foreclose reflection of our own uses and the ambiguous relationships that businesses have with the motives for the consumption, uses, and effects of these substances.

The survey – conducted in two large public and private organisations – reveals, among other things, that reporting of problematic use or treatment is rare as long as the work gets done. In addition, the hierarchy shapes the visibility of these uses. To report substance use often amounts to creating a problem that management is rarely trained to address.

Jettisoning Current Stigmatising Approaches and Prevention

Se doper pour travailler, Editions ERES, Prix du livre RH 2018

It is also important to jettison current approaches focused on legal (drugs, alcohol, nicotine) or illegal (cannabis, amphetamines, cocaine, etc.) substances that only consider their use as workplace misconduct or risk: misconduct because some of these uses are legally or morally condemned, and risk because the organisations involved in occupational health prevention only consider these uses through the prism of safety concerns, absenteeism, disorganisation of services, and workplace accidents. However, this dual misconduct/risk focus sidesteps analysis of the tensions, responsibilities, and collective dynamics that explain employees’ use of products. Stigmatising certain substances and dismissing their users preclude probing what types of organisation and working conditions are deleterious to employees’ health. This polarisation also closes the door to thinking that the more or less hidden uses paradoxically help maintain unhealthy organisations.

To overcome these obstacles, our research valued pluralism. We sought the voices of researchers, employees, and various players in the occupational and care worlds(4)CRESPIN, Renaud, LHUILIER, Dominique, et LUTZ, Gladys, Se doper pour travailler, Toulouse, Érès, 2017.. Each in their own way, these voices show that intensifying productivity requirements, lack of cooperation within and between teams, intense competition, and fear of losing one’s job, are key to understanding PS practices.

Psychoactive Substances and Work Resources: Four Use Cases

This shared observation led us to consider these uses as resources for both organisations and employees. Depending on the job and the position held, pharmacological boosters are thus akin to work tools. They are alternative solutions when the prospects of transforming work dim or disappear. We identified four professional use cases for psychoactive substances.

- Anaesthetising to Keep Up

© istock

Respondents regularly used the phrase ‘keeping up’. It refers to the physical and mental workload, to the need to keep up the pace, to ‘keep going’, to ‘get the job done’ notwithstanding any difficulties. One of our respondents, an actress who also works as a waitress to increase her income, told us how much her cocaine use helps her cope with her workload: ‘At times, coke is a great ally in helping me do many things. At times it was what kept me going. It could have been a prescription.’

Professionals with musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs, the leading identified cause of occupational illnesses) are also in this situation; they know that their health condition affects their movements and may jeopardise their employment. The use of painkillers – regardless of whether they are illegal or prescribed – can help make the work bearable. Other substances can also be used to alleviate anguish, shame, guilt, or boredom. Alcohol consumption also pertains to specific work situations, be they particularly trying events or daily work constraints identified, for example, in firefighting and law enforcement professions.

- Stimulate, Disinhibit, Succeed

Staying awake, ‘rallying’, optimising one’s mental and physical capacities and results, ‘stimulating oneself’, ‘concentrating’ and ‘boosting confidence’ to meet the demands of the job: these quests for performance appear across accounts of substance use at work. They reveal objectives centred on production, rallying, acuity, concentration, challenges, and milestones to achieve. Although it is related to doping, this use case is less common than the others. It differs from doping because, performance aside, it stems from a desire to ‘do one’s job well’.

© Shutterstock

A small business manager described how her ability to concentrate and generate ideas is associated with smoking: ‘Every time I was designing, I couldn’t sit in front of my computer without cigarettes. When we had to stop smoking in the office, I said to myself: I can’t ideate, I have no stimulation, I need my stimulation. (…) and to relax while also moving forward: cigarettes. I smoke in the office when I am alone in the evening.’

An architect also described how cannabis helps him overcome blank page anxiety. Smoking defangs the fear of failure while sharpening concentration: ‘There is the terrible moment when ideas aren’t coming and you feel like you’re never going to get there: that’s when smoking can help me. That’s when I stop myself from thinking I’m not going to make it and just get on with it (…) the drawing takes over. I forget about my stressful situation and really get into it.’

- Recover

Being able to sleep, relax, and decompress after intense activities in order to be ready to move onto the next work project, is a recurrent use case of recovery associated with occupational PS use. The example of a young production manager in the audiovisual sector illustrates the extent to which work organisation and conditions influence this type of use. Over an eight-month trial period, she was supposed to send in a program made during the day every evening. She would get to the office at 10 a.m., receive the images in the afternoon, and write and edit her project in the evening, before returning home at 2 a.m. And start all over again the next day. To keep up, she drank coffee and smoked all day long, often had a drink at noon with the teams, a line of coke in the evening to be able to finish in time, and then sleeping pills to fall asleep: ‘otherwise I couldn’t sleep and I knew it was going to be even harder the next day.’

- Integrate and Maintain Professional Relationships

This mainly pertains to collective uses of alcohol and its role in lubricating professional socialisation and sociability for work. The pull of collective use norms is commensurate with the stakes of belonging to work contexts where interdependence is key.

© Shutterstock

These group uses are linked to collective, cooperative, cohesive, identifying, and defensive work dynamics counteracting physical fatigue, hierarchical power, emotional isolation, incidents, and professional disillusionment. These collective practices are sometimes part of the underground life of organisations: the transgression of the prohibition they imply helps strengthen bonds to and through work.

As a firefighter testified, ‘It’s a barracks environment, so we know very well what our job is. We’re all buddies, we come back from an incident, and we have a drink in the foyer.’ The term ‘buddies’, often associated with ‘breaks’ or relaxation, always connote the idea of good relations, and especially good work and good work regulations. This daily socialisation also involves welcoming newcomers; the ability to consume in accordance with collective norms secures belonging. A journalist thus relates his ‘first experience with alcohol at work. I was working in radio, on a mandatory third-year internship, and the guys were drinking. From six o’clock onwards, we drank aperitifs every night. Those are my first memories of chronic drinking over several days. I have memories of still being on the radio at 11 p.m. and still drinking.’

The Need for Detailed and Contextualised Analysis for Customised Prevention

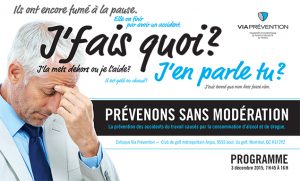

Colloque Via Prévention sur la prévention des accidents du travail causés par la consommation d’alcool et de drogue. Association paritaire pour la santé et la sécurité du travai

Drawing on these use cases, we see a path reflection on prevention. This requires dissociating PS use of addiction without overlooking the issue of the transition from casual use to addiction. In fact, to shift from use to addiction is to shift use cases: the use then becomes about satisfying personal cravings rather than overcoming challenges and continuing to work ‘well’.

Our objective is to encourage prevention without reducing the problem to a fault or sanction, as drug testing can do, or to an individual disease, as the addiction approach suggests. Proposing an alternative to the medicalisation of social issues involves anchoring prevention in a detailed and rooted analysis of work and substance use.

Renaud Crespin is a CNRS research fellow at the Centre for the Sociology of Organisations (CSO). His work combines three analytical perspectives: the sociology of public action, the sociology of science and technology, and the sociology of work. His research probes public action rationalisation processes in the fields of health and the environment. He compares the instrumentation of prevention policies in different areas of activity. He also studies how technical-scientific expertise shapes public health issues.

Complementary bibliography

- Crespin, Renaud. 2018. « Du soin à la prévention des risques : La carrière des tests de dépistage des drogues dans le monde du travail (États-Unis/France). » In La mesure du trouble mental : Psychiatrie, sciences et société, ed. Philippe Lemoigne, 217-262. Londres : ISTE éditions. Ingénierie de la santé et société.

- Crespin, Renaud. 2018. ‘From Care to Risk Prevention: The Success of Screening Tests for Drugs at the Workplace: United State / France.’ In Measuring Mental Disorders: Psychiatry, Sciences and Society, ed. Philippe Lemoigne, 183-234. London : ISTE Press.

Notes

| ↑1 | Villermé, L. R. (1986). Tableau de l’état physique et moral des ouvriers employés dans les manufactures de coton, de laine et de soie (2 volumes, 1840). Réédition sous le titre Tableaux de l’état physique et moral des salariés en France. Paris : La Découverte. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | These surveys were mainly carried out with Dominique Lhuilier and Gladys Lutz as part of the PREVDROG-Pro research project funded by Mildeca and INCA (2011-2014) then continued in the SURIPI project funded by ANSES (2016-2021). |

| ↑3 | Crespin, R. (2015). Le sens des mesures. Usages et circulation des chiffres dans la définition du problème public des drogues au travail. Psychotropes. |

| ↑4 | CRESPIN, Renaud, LHUILIER, Dominique, et LUTZ, Gladys, Se doper pour travailler, Toulouse, Érès, 2017. |