Wage Inequality: the Price of Motherhood

13 June 2022

Are Elected Officials Compensated for Working?

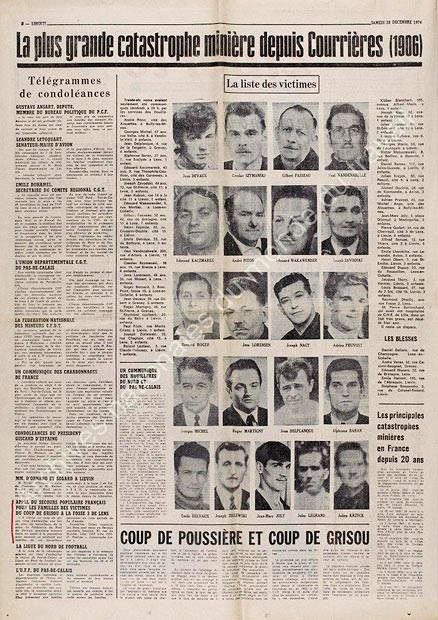

13 June 2022 On December 27, 1974, an explosion occurred in one of the tunnels of the Liévin coal mine in northern France. Forty-two miners were killed on the spot: it was the most serious French mining disaster of the post-war era, and one of the last too(1)Marion Fontaine, Liévin 74. Fin d’un monde ouvrier, Éditions de l’EHESS, 2014..

On December 27, 1974, an explosion occurred in one of the tunnels of the Liévin coal mine in northern France. Forty-two miners were killed on the spot: it was the most serious French mining disaster of the post-war era, and one of the last too(1)Marion Fontaine, Liévin 74. Fin d’un monde ouvrier, Éditions de l’EHESS, 2014..

The End of Heroes

The images and speeches from the funerals of the victims a few days later appear to attest to historical continuity at first glance. A series of leitmotifs ran from the end of the 19th century throughout the 20th century: the same images of pained widows, and of the heroism and martyrdom of the ‘black faces’; and an identical horrified fascination for the underground world and man-eating mine, dating back to Germinal (1885). This visual illusion of persistence is misleading, however. All the signs of a profound change were actually already apparent.

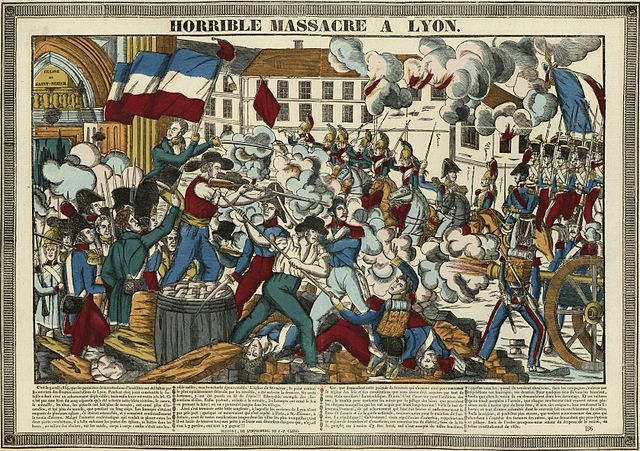

Indeed, in 1906, at the time of the epic disaster at Courrières (1,099 victims!), the socialist leader Jean Jaurès incriminated mining companies on risk prevention and rescue operations. Yet he did not deny the ‘fatality’ involved in handling natural forces and the intrinsic danger of the profession, which reforms (wages, social protection, nationalisation) could help address, but which miners at the vanguard of industrialisation had to heroically shoulder. ‘This mine where they toil and succumb, this mine that is always a difficult worksite and sometimes a sinister tomb: they love it despite of everything; because man loves what he devotes himself to. But how much more they would love and embrace an underground city of free labour and social justice.’ (L’Humanité, March 11, 1906).

Nothing of the sort was discernible in 1974. Heroism had given way to sorrow, and above all to the shared feeling that the 42 victims had died for nothing – or nothing worthwhile in any case. A local newspaper bluntly observed: ‘These funerals in Liévin may also mark the death of an era: one in which people were resigned to accepting “fatality”, and work in the mine as a fatality.’ (Nord-Eclair, January 2, 1975). The sentence reflects a specific context: the decline of the coal industry was already very advanced in France at that time, and sacrificing one’s life for coal when it was a dying industry did not seem to make much sense anymore. But the quote is also indicative of a more general evolution, whereby miners became actors refusing the fatality of workplace risk for either accidents or disease. In other words, the idea took hold that these risks had causes and that people were responsible for them, and that the former needed to be fully stemmed, while the latter needed to be identified and held accountable.

Mines as a Field of Experiment

Disaster of Courrières – Women seated in a circle waiting on the floor of the Fosse de Sallaumines. Public Domain

A case like this leads to research paths at the intersection of history and the sociology of work, environmental history, and the sociological approach to collective risks(2)See for example Yannick Barthe’s work, Les retombées du passé. Le paradoxe de la victime, Le Seuil, 2017..

That work could kill either brutally or insidiously, through exposure to toxic substances for example, was a well-known fact in the 19th century, giving rise to considerable controversy among labour representatives, employers, and public authorities: such was the case for the use of phosphorus and lead in certain sectors (3)Judith Rainhorn, Blanc de plomb. Histoire d’un poison légal, Presses de Sciences Po, 2019. .

The industrialist and productivist paradigm, which became increasingly prevalent at the turn of the century, including in the labour movement, tended to consider this type of risk as fatal and inherent to the nature of industrial work. As Welfare States became stronger, the issue became less about risk elimination or prevention and more about it than about reparations for its consequences a posteriori, notably through financial compensation. While this phenomenon is now well known, the challenge is to understand how and why the paradigm broke down, or at least became increasingly contested, particularly beginning in the 1960s–1970s(4)Renaud Bécot, Syndicalisme et environnement en France de 1944 aux années 1980, Thèse pour le doctorat d’histoire, EHESS, 2015..

Minor with silicosis, near Lens (Pas-de-Calais), 1951. © Donation Willy Ronis, Ministry of Culture (France), Multimedia Library of Architecture and Heritage, broadcast RMN-GP

Both the Western and non-Western mining worlds, which have been the subject of profound historiographical reappraisals in recent years, appear to be an appropriate field to grasp and think about this change(5)Marion Fontaine, « Les Mines, un terrain d’expérience », Cahiers Jaurès, n°230, octobre-décembre 2018.. It is one of the sectors where the industrialist norm and negation of risks, or at least the solely monetary approach to compensation, were the most salient. During the 20th century, miners continued to die in spectacular catastrophes, but they died much more from diseases such as silicosis(6)Paul-André (dir.), Silicosis. A World History, John Hopkins University Press, 201.

In France, even the nationalisation of mining companies (1944–1946), which Jaurès fervently called for, did not change much. The new nationalised mining company recognised the origin of silicosis, but nonetheless perpetuated, if not amplified, a system where the imperative to modernise production paired with a relative indifference and very arbitrary management of its health consequences.

‘De Fatalizing’ Work Risk?

The goal is to understand what changed and the elements of social and political modernisation that transformed this system, and more generally the understanding of risks associated with mining work(7)Richard Berthollet, Marion Fontaine, La grande tueuse, documentaire télévisé 52’, D-Vox production, 2021..

Several factors were involved. The first was the evolution of the workers’ worlds themselves. In the large basins of the North and Lorraine, rising levels of education, the circulation of information, and alternatives to working in the mines increased throughout the ‘Trente Glorieuses’ period of high growth. Mining health risks were undoubtedly clearer and better understood by the miners and their families, resulting in a flight from the profession, if not for existing miners themselves, at least for their children. The change was also intellectual and political. It led to qualifying the simplistic divide between the land of heavy industry – the stronghold of a traditional, productivist left, focused on quantitative demands – versus the aspirations and new forms of mobilisation that emerged around health and work environment issues during the ’68 era. This so-called ‘delay‘ or gap was relative. Far left-wing activists, especially Maoists, campaigned in the coalfields during these years. Although there were only a handful of them, they offered a new interpretation of accidents and occupational diseases. In Liévin and elsewhere they called for ‘refusing fatality’ in the mines and for the responsible doctors, engineers, and managers to be identified, denounced, and tried.

Miners’ strike on May 11, 1968 on the market square in Forbach. Photos Paul de Busson / Christian Fauvel Collection1 /48

These activists did not succeed in bringing about a vast mobilisation, but their ideas spread in unions such as the CFDT-Mines(8)The CFDT (Democratic labor confederation) was founded in 1964. In the1960s and 1970s, it represented a self-managing trade unionism that very early on focused on quality of life issues at work.. Although the CFDT-Mines remained a minority compared to the CGT, it made significant progress, particularly in Lorraine. By combining the influences of Christian personalism and the movements of 1968, the CFDT-Mines offered a new reflection on the miner’s profession and its risks. Here again, the idea was to assert that these risks were neither natural nor normal, and that it was possible to prevent them by changing the work of organisation, environment, and hierarchical structures. It was possible to modernise the profession and to conceive of underground work where accidents and illness were not inevitable hazards, but rather exceptions.

A Relevant Issue

The mines, an archetype of industrial work, thus constituted a field of experimentation and debate for developing a more reflective and critical approach to the forms of this work, and in particular the underlying relationship to risk. It is interesting to note that one of the young Maoist activists working in the northern basin at the time – the philosopher François Ewald – would later use this experience as one of the starting points for his work on the welfare state and risk management(9)François Ewald, L’État-Providence, Grasset, 1986..

Not to exaggerate the significance of mining. The coal industry crisis and accompanying deindustrialisation quickly dried up these reflections, and the miner’s profession disappeared in France and across the West, less for environmental and health reasons and more for lack of economic viability. However, mobilisations linked to risk exposure did not disappear in the former basins.

Retired coal miners from Lorraine demonstrate in front of the Douai Court of Appeal, September They want to have their anxiety recognized by denouncing their exposure to numerous toxic products at work. They are claiming compensation from the former employer, Charbonnages de France. Photo archive RL

The CFDT-Mines of Lorraine continue to mobilise in the legal field to recognise victims and fault operators over recognised occupational risks. In this mobilisation, the mining past has resurfaced in connection with new claims relating to occupational health risks: the CFDT-Mines has thus underscored the ‘detrimental anxiety’ to which former miners are exposed – a legal term used in asbestos trials that is now being reused to describe the burden of the mining past for pensioners and their families.

Thus, reflection on industrial work, its criticisms, and the mobilisations that have accompanied them, is not an anachronistic undertaking that has no bearing on the present. Post-industrial work, for want of a better term, still involves different forms of exposure to risks(10)Philippe Bernard, « Les accidents du travail tuent en silence », Le Monde, 29 January2022., and its history is far from over.

Marion Fontaine, Centre for History

Marion Fontaine is a university professor affiliated with the Sciences Po Center for History. Her research focuses on political and cultural history (20th-21st-century Europe), the history of socialism and the labour movement, the history of mines and miners, and the crisis of industrial societies. She is also interested in the history of social time and leisure (sports). Her most recent work focuses on the history of mining, the history of the crisis of industrial societies, and the history of socialism and the labour movement.

Notes

| ↑1 | Marion Fontaine, Liévin 74. Fin d’un monde ouvrier, Éditions de l’EHESS, 2014. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See for example Yannick Barthe’s work, Les retombées du passé. Le paradoxe de la victime, Le Seuil, 2017. |

| ↑3 | Judith Rainhorn, Blanc de plomb. Histoire d’un poison légal, Presses de Sciences Po, 2019. |

| ↑4 | Renaud Bécot, Syndicalisme et environnement en France de 1944 aux années 1980, Thèse pour le doctorat d’histoire, EHESS, 2015. |

| ↑5 | Marion Fontaine, « Les Mines, un terrain d’expérience », Cahiers Jaurès, n°230, octobre-décembre 2018. |

| ↑6 | Paul-André (dir.), Silicosis. A World History, John Hopkins University Press, 201 |

| ↑7 | Richard Berthollet, Marion Fontaine, La grande tueuse, documentaire télévisé 52’, D-Vox production, 2021. |

| ↑8 | The CFDT (Democratic labor confederation) was founded in 1964. In the1960s and 1970s, it represented a self-managing trade unionism that very early on focused on quality of life issues at work. |

| ↑9 | François Ewald, L’État-Providence, Grasset, 1986. |

| ↑10 | Philippe Bernard, « Les accidents du travail tuent en silence », Le Monde, 29 January2022. |