Truth without Justice? Law in the Face of Mass Crimes

16 April 2023

Imperialism Revealed in the War. Russia Exposed

16 April 2023On 12 October 2022, the French President seemed worried about the growing number of references to nuclear weapons in the public arena following Russian threats, and declared on the France 2 national television channel: ‘The less we talk about nuclear weapons, the more credible they are.’ It is certainly the case that we usually do not talk about them, except during occasional panics whenever a crisis or a threat suddenly reminds us of the destructive capacity of these weapons and the inability of states to protect their populations from nuclear explosions.

The State of Nuclear Weapons in 2023

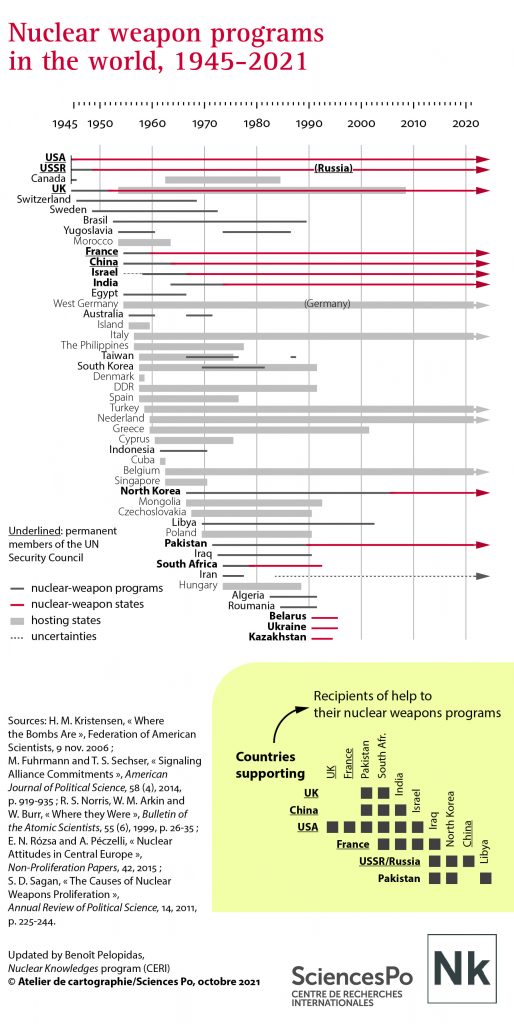

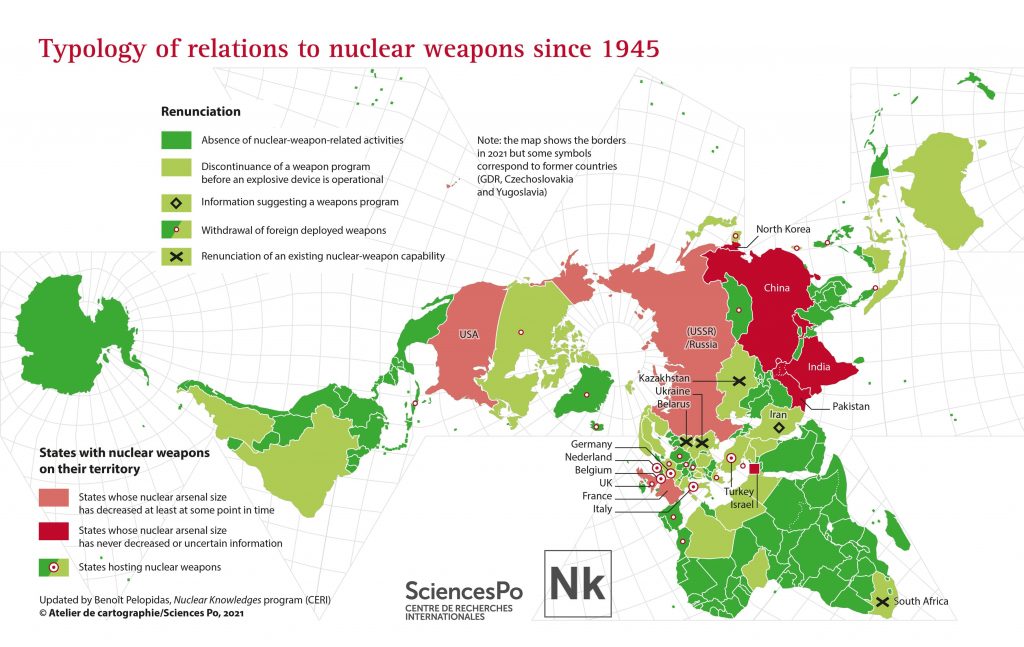

There are more than 12,000 nuclear weapons in the world as of 2023, in the hands of nine states (in chronological order of acquisition of nuclear weapon systems: the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Israel, Pakistan, and North Korea), plus five NATO member states (Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Turkey) that hosts American nuclear weapons. These fourteen states are all located in the Northern Hemisphere.

The vast majority of these weapons have a greater destructive capacity than the bomb that levelled the city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. The United States and Russia alone possess more than 90 percent of the world’s nuclear weapons, but this figure is misleading because the smaller nuclear arsenals of the other nuclear states are also capable of ending civilisation as we know it. If 1% of these weapons were to be detonated on cities, current climate models suggest this would result in a ‘nuclear winter’ that would produce a global famine likely to kill over a billion people. Finally, in 2021, there were 1,800 tons of highly enriched plutonium and uranium left on the planet – enough to make more than 195,000 bombs similar to the one that destroyed Hiroshima.

Two observations must be added to this state of affairs. First, analysts and intelligence services have grossly overestimated the desire of non-nuclear-weapon states to acquire nuclear weapons. In fact, the demand for bombs has been fed by the rhetoric of nuclear-armed states, including the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, which present them as an indispensable, strictly defensive, and risk-free guarantor of national security, and by the technology transfers in which these states have engaged. Second, it is essential to bear in mind that the effects of the world’s nuclearisation are not all known.

Moreover, the extreme difficulty of locating nuclear ballistic missile submarines combined with the acceleration in their ability to deliver nuclear violence – ballistic missiles move around twenty times faster than the bombers that used to carry the explosives – has made it almost impossible to destroy the explosive before it is launched or to intercept it before it reaches its target. Hence, since the beginning of the 1960s at the latest, it is no longer possible to protect populations from these explosions. Being reassured Itby the absence of unwanted nuclear explosions thus far would, however, be wrong.(1)It is also false to say that nuclear weapons have only exploded twice, in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Nuclear-weapon states have conducted more than 2,000 nuclear tests with massive health and environmental consequences..

Why Nuclear Explosions Remain Possible: Five Reasons

Nuclear explosions against which there is no protection remain possible for five reasons.

First, the practice of nuclear deterrence requires this possibility. Contrary to the idea that nuclear deterrence provides ‘strictly defensive’ protection, it actually requires convincing the potential enemy that one has the capability and determination to cause unconscionable harm. The strategy is thus based on threat and the development of strike capabilities, routines, employment and communication plans in the hope that they will impact the enemy.

Second, the nuclear doctrines of nuclear-weapon states also mention the possibility of nuclear strikes. Indeed, with the exception of India and China, none of the nuclear-weapon states – the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, Israel, Pakistan, and North Korea – has a no-first-use doctrine for their nuclear weapons. Despite candidate Biden’s campaign promises, this ‘no-first-use’ principle is not reflected in the U.S. nuclear position, the unclassified version of which was released in late October 2022. This document (page 9) makes clear that while Biden’s declared policy change was considered, it was ultimately rejected in the long process of reviewing the U.S. nuclear strategy.

We also know that the size of the Russian and U.S. arsenals far exceeds what would be required for the sole purpose of nuclear deterrence as defined by their respective military leaders. The size of these arsenals can only be explained by considering secondary objectives that entertain the possibility of nuclear strikes: ‘limiting damage’ by destroying the enemy’s nuclear weapons before they are launched if deterrence were to fail, but also, at least in the early years of the nuclear age, the ability to execute preventive strikes or to fight and win a limited nuclear war.

A fourth indication that nuclear strikes remain possible is that nuclear war games and simulations, including those involving practising officials, frequently result in the use of these weapons.

A fifth and final clue is that we have in the past prevented accidental nuclear explosions thanks to failures of control practices or independently from control practices, showing that these controls have not eliminated the possibility of nuclear explosions.

Finally, it is important to bear in mind that we are most likely underestimating the number of past cases of lucky close calls since most nuclear-weapon states are not transparent about these cases and national defence and nuclear secrecy make it impossible to know whether such cases have taken place in recent decades.

For these five reasons, it is essential to realise that nuclear explosions remain possible. This is crucial not only because of the devastating consequences of a nuclear explosion, but also because of the difficulty of containing escalation once a first explosion occurs.

Why We Find It Hard to Believe in Our Nuclear Vulnerabilities

These dark realities are hard to believe and to accept, which makes us ‘lazy people of the apocalypse’ to use the term of German philosopher Günther Anders(2)Günther Anders, “L’homme sur le pont” [the man on the bridge], Journal d’Hiroshima et de Nagasaki, 1958, cited in Günther Anders, “Hiroshima est partout”, [Hiroshima is everywhere], Seuil, 2008, p. 194... Beyond the psychological problem of our relative insensitivity to very large numbers, we have wrongly convinced ourselves that nuclear explosions are no longer possible for three reasons.

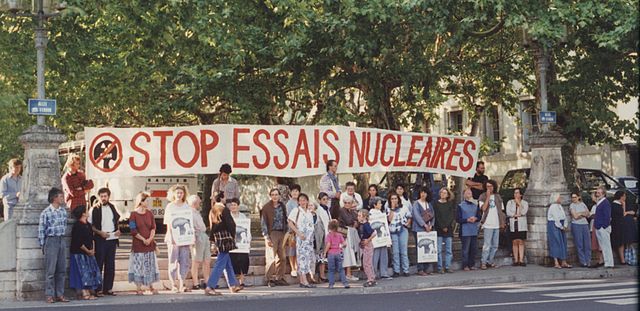

Demonstration against nuclear tests, Lyon, France. 1980s. Community of the Ark of Lanza del Vasto., CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

First, these explosions were removed from the realm of direct human experience in 1980 when all nuclear tests went underground.

Second, quasi-official experts from nuclear-weapon states cannot be trusted to provide a complete picture of nuclear vulnerabilities, because their role is not only to describe the situation, but also to convince people of the credibility of the national nuclear deterrence policy. Therefore, if they were aware of any limitations of this policy or particular vulnerabilities in their country’s arsenal, they would not reveal them anyway.

Finally, regardless of how familiar one is with nuclear issues, it is hard to believe in the possibility of such explosions. And the popular visual culture of the 1950s through the late 1980s-early 1990s, that aesthetically immersed people in a fictional world in which these were possible, no longer helps us overcome our disbelief.

Reconciling Nuclear Realities With Beliefs Through Collaboration Between Independent Research and Artists

At a time when nuclear-weapon states have launched programs that extend the life of their weapons for decades and even until the end of the century, and when a movement calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons is taking shape around the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (2021), we need to be able to make informed decisions without being blind to our nuclear vulnerabilities.

This ‘we’ is inclusive in that we cannot choose not to be affected by the nuclear policies of nuclear-weapon states. As residents and/or citizens of a nuclear-weapon state, we are already affected: as taxpayers, the state expects us to agree to fund the national nuclear arsenal; as citizens, the state expects us to delegate to the head of state the authority to implement the national nuclear doctrine, since in the event of an attack consultation would not be possible due to time constraints; and as residents we are prime targets. It is important to remember that the sizing of a potential enemy’s arsenal aims to limit the damage that can be caused by preventively destroying the enemy’s weapons – including those located on national soil. As citizens, we are not free to choose whether or not to be affected by nuclear policies; we can only choose to be active or passive in reacting to these policies.

For those who would like to be active, independent research and the arts are two key pillars. By independent research, we mean practices of knowledge production free from funding that involves conflicts of interest and which does not treat actors’ categories and judgments as though they were neutral analytical categories. This effort enables a clear debate on the bets on the future, value choices, and memories of the past on which proposed policies are based. This is all the more important that independent research alone has shed light on the role of luck in avoiding unwanted nuclear explosions, the health effects of nuclear testing and their consistent underestimation, and the lack of consensus among the French about nuclear deterrence.

But this is not enough. Given our disbelief when faced with the established possibility of nuclear explosions, artists have an essential role to play in helping us believe in what we can prove about nuclear vulnerabilities – in other words, to overcome our disbelief. They played this role during the Cold War, including with elites. They can do so again, probably through new approaches. This is the only way we will be able to clearly ask the question: what weapons systems for what defence policies for our political community now through 2090? Clearly asking means not giving in to the facile notion that tomorrow’s enemy would necessarily correspond to the weapons that our state is planning to build today; that no explosion – deliberate or accidental – would occur in a scenario affecting the said state; that silences produce the desired effects, as the President hopes, and that nuclear vulnerabilities do not exist because we do not want to or cannot believe in them.

Associate Professor Benoît Pelopidas is the founder of the Nuclear Knowledges program and previously held the Chair of Excellence in Security Studies at Sciences Po (CERI) (2016–2019). He has been awarded grants from the European Research Council (ERC) and the French National Research Agency (ANR) to study nuclear choices. He is also a Research Affiliate at the Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC) at Stanford University in the United States and a frequent visitor to the Global Systemic Risk Group at Princeton University. He has received three international academic awards for his research.

References

Kjølv Egeland and Benoît Pelopidas, ‘No such thing as a free donation. Research Funding and Conflicts of Interest in Nuclear Weapons Policy Analysis,’ International Relations, early view

Kjølv Egeland and Benoît Pelopidas, ‘European nuclear weapons. Zombie debates and nuclear realities,’ European Security 30(2), 2021, pp. 237–258.

Benoît Pelopidas, Repenser les choix nucléaires. La séduction de l’impossible. [Rethinking nuclear choices. The seduction of the impossible] Paris: Presses de Sciences Po, 2022, preface by David Holloway, 308p.

Benoît Pelopidas, “The unbearable lightness of luck. Three sources of overconfidence in the manageability of nuclear crises,’ European Journal of International Security 2(2), 2017, pp. 240–262.

Benoît Pelopidas, ‘Power, luck and scholarly responsibility at the end of the world(s)’, International Theory 12(3), 2020, pp. 459–470.

Sébastien Philippe, Sonya Schoenberger, and Nabil Ahmed, ‘Radiation Exposures and Compensation of Victims of French Atmospheric Nuclear Tests in Polynesia’, Science and Global Security 30(2), 2022, pp. 62–94.

Hebatalla Taha. ‘Hiroshima in Egypt: interpretations and imaginations of the atomic age,’ Third World Quarterly 43(6), 2022, pp. 1460–1477

Notes

| ↑1 | It is also false to say that nuclear weapons have only exploded twice, in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Nuclear-weapon states have conducted more than 2,000 nuclear tests with massive health and environmental consequences. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Günther Anders, “L’homme sur le pont” [the man on the bridge], Journal d’Hiroshima et de Nagasaki, 1958, cited in Günther Anders, “Hiroshima est partout”, [Hiroshima is everywhere], Seuil, 2008, p. 194. |