Youth in France: “a rejected citizenship”

30 September 2017

Commemorating the Holocaust After the War

2 October 2017

Au fil du flux Le travail de surveillance-contrôle dans les industries chimique et nucléaire. Presses des Mines

D

ebates over the place of work in our society are somewhat paradoxical. Whether technology is being touted for its potential or denounced for its domination, both supporters and detractors agree that work will inevitably disappear. Has technology uncoupled from work?

What better way to answer this question open-mindedly than through sociological fieldwork? Gwenaële Rot, a Sciences Po university professor and researcher at the Center for the sociology of organizations, and François Vatin, a sociology professor at Paris Nanterre University and researcher at IDHES, tackled this question. They presented the findings in their book “Au fil du flux. Le travail de surveillance-contrôle dans les industries chimique et nucléaire” [Following the flows. Surveillance-control work in the chemical and nuclear industries]. Highlights

Working, a productive action

Given the idea that work is destined to disappear in the face of technological prowess, the authors seek to clearly define work as an activity recognized to be “productive”, their intent being to draw our attention to the fact that regardless of the sources and/or terms of this recognition (oneself, one’s peers, the organization, the market, etc.), a human activity is considered work if it contributes to production. They therefore call for (re)-thinking the value of work by precisely describing the concrete terms of the activities and their forms of social recognition, regardless of the sector, productive process and level of responsibility.

Monitoring machines

Chemical industry worker at factory. Crédits : Dmitry Kalinovsky, Shutterstock

Through a concrete study of the activities of operators in the chemical and nuclear industry – a highly automated industry – Gwenaële Rot and François Vatin ask simple questions in this book. What do operators of such facilities do on a daily basis, considering that people’s time schedule is disconnected from that of machines? How do workers cooperate when professional responsibilities are difficult to attribute individually but are significant due to the potential consequences of error? How are these workers assessed by their peers and by management? In sum, what does “work” mean in this context?

“We do not make marshmallows here”

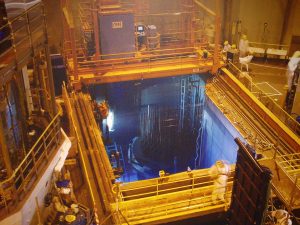

Centrale nucléaire de Gravelines- Piscine, by Serge Ottaviani. CC BY-SA 3.0

Answering this question requires identifying the productive values in flow industries, which inextricably involve “getting the product out” and ensuring security in plants where, as they say, “we do not make marshmallows”. In this context, conflicting imperatives must be addressed: short-term goals (get the product out) cannot undermine mid-term goals (the reliability of the process) or long-term ones (the security of the facilities). But long-term goals in turn undermine short-term ones in a world marked by a growing bureaucracy, especially because of public norms spread throughout the organizational chain as everyone seeks “cover”.

The organization of these plants is characterized by cooperation/opposition games between the desk managers who follow the production from their screen and the floor men who monitor the physical state of the facilities in situ, as well as between the “shift workers” who work “on a three-shift basis” and the “day workers”. This complex organization creates redundancies and turf conflicts, but despite the apparent confusion it also ensures the collective achievement of strongly conflicting requirements.

Rethinking work

Thus, the field study of a very specific production context provides insight on overarching issues linked to contemporary transformations.