The slums of Mumbai, regulated anarchy

12 October 2017

The waste crisis and urban fabric in Beirut

12 October 2017Political scientist, Laurent Gayer is a CNRS researcher at Sciences Po’s Centre for International Relations (CERI). His research focuses on the Indian subcontinent region and principally explores urban dynamics and violent mobilizations. Here, he presents the major dynamics behind armed conflict in Karachi, Pakistan’s preeminent city in terms of population and of contribution to the national economy. In contrast to portrayals of Karachi as an anarchic megalopolis, he shows that these conflicts have specific patterns and rationales related to power sharing between the city and its region.

Karachi, how many divisions?

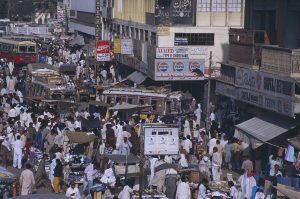

People in Karachi, 1990 By Ziegler. CC BY-SA 3.0

The battle over figures is therefore not neutral and provides a window into the struggles playing out in the city.

Karachi, a mini-Pakistan

![Karachi by NASA [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Karachi by NASA [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Karachi_Pakistan_2010-01-08-300x200.jpg)

Karachi by NASA [Public domain]

The city’s enduring attractiveness despite the nefarious reputation it has earned from its political troubles and criminal violence, is attributable to its economic dynamism. Here again, the available, barely updated figures are contested. The city accounts for an estimated 15-20% of Pakistan’s GDP and 30% of its manufacturing sector; close to 90% of foreign trade transits through its port; and the city is home to 50% of the country’s bank reserves.

From province to municipality

As a constantly changing international city, Karachi has the reputation of being ungovernable. This reputation primarily derives from the competition between public actors fighting for control over the city. In 1846 British colonizers created the local government’s leading institution, the Karachi Conservancy Board, in response to a cholera epidemic. In 1933 its powers were expanded, giving birth to the Karachi Municipal Corporation. Now called the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation, the institution is currently led by a mayor indirectly elected by the councilors of Union Councils (subdivisions of major neighborhoods including between 30,000 and 60,000 residents), who are elected by universal suffrage.

Despite the organization’s conventional appearance, power sharing between the local and provincial authorities has provoked major tensions over the past few years, resulting in massive violence. These conflicts are rooted in a 2001 national reform of local governments that transferred unprecedented powers and resources to the municipality at the expense of the provincial government.

Reform against the backdrop of political and ethnic issues

Portrait d’Altaf Hussain, le leader du MQM, dans le quartier colonial de Burns Road (2010). Crédits : Laurent Gayer

The “local” and “managerial” dimensions of this reform reflect national political and partisan struggles that, as always in Pakistan, have an ethnic element.

Pakistan’s successive military regimes since the end of the 1950s have consistently seen local democracy as an opportunity to weaken the major regional and national parties through the promotion of new local elites. Pervez Musharraf, who ascended to power after a coup d’état in 1999, considered the reform as a means to consolidate his power in the region of Sindh and at the national level by weakening his main political nemesis: the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). The latter’s stronghold was in the Sindh’s rural areas, but it also influenced the management of Karachi through its hold on the Sindhi-dominated provincial bureaucracy. Furthermore, Pervez Musharraf seized on the reform as an opportunity to strengthen the principal counterweight to the PPP in the province: the Muhajir Qaumi Movement, which has represented the Muhajir Urdu-speaking community (of which he is a member) since the second half of the 1980s, by systematically winning a majority of the seats attributed to Karachi at the national and provincial assembly.

However, the Muhajir Qaumi Movement never succeeded in governing Karachi without sharing power. Various public services remain under the provincial government’s authority, particularly the police. The latter is all the more supportive of the provincial government and of the Pakistan People’s Party that the PPP has encouraged the massive recruitment of Sindhis** in law enforcement, simultaneously ethnicizing and politicizing the police to its advantage.

Reclaiming the city through violence

Graffiti pacifiste sur un mur du quartier colonial de Saddar (2014)- Crédits : Laurent Gayer

In 2011, under pressure from some of its Sindhi leaders, who were bent on weakening the Muhajir Qaumi Movement in the province, the Pakistan People’s Party attempted to transfer some of the city of Karachi’s resources and powers to the provincial administration. In response the Muhajir party, which had until then been working, for better or worse, with the Pakistan People’s Party, quit the provincial government and deployed its militias in several of the city’s neighborhoods. Since its creation in 1984, the Muhajir Qaumi Movement has built its power on the basis of both electoral success and muscular, if not criminal, methods (extortion, torture, targeted assassinations). In addition to its involvement in ordinary acts of violence, it developed an art of negotiation based on the threat of chaos by using the weapon of the general strike. Each call for a strike immobilized the city: industry, businesses and transporters halted their activities out of fear of retaliation. These blockades were systematically accompanied by violence – especially against buses, which are mostly owned by Pashtun transporters with whom the MQM has always had hostile relations. During the summer of 2011, the Muhajir Qaumi Movement used this strategy once again to force the Pakistan People’s party to withdraw its reform.

When criminals enter the game

Un quartier contesté de Lyari, en proie à la violence des gangs (2013) – Crédits Laurent Gayer

This time, the Muhajir Qaumi Movement met strong resistance from armed groups that had consolidated over the previous years in reaction to its attempts to impose its rule. One was the Awami National Party, a Pashtun nationalist party intent on resisting the MQM through arms and challenging its control over certain criminal acitivities (such as extortion and illegal land occupation). The Muhajir Qaumi Movement also faced the resistance of criminal gangs from the Lyari neighborhood – Karachi’s rough inner city. A PPP bastion, this neighborhood has always provided its party with shock troops. Under the tutelage of the provincial minister of the interior, Zulfikar Mirza, who openly appeared with their “dons”, the Lyari gangs became the PPP’s informal armed wing and entered into a bloody conflict with the Muhajir Qaumi Movement.

In the summer of 2011, clashes that mainly involved political party members and the criminal organizations they sponsored, claimed hundreds of victims. However, the violence spilled over to the civilian population several times, on the basis of ethnicity. As the risk of a general conflagration grew, the Pakistan People’s Party temporarily retreated. Two years later, the provincial government nonetheless succeeded in passing a reform that granted it more power, much to the discontent of the Muhajir party.

Thus, while the latter once again won the municipal elections in 2015, its victory was bittersweet: in addition to being deprived of most of its resources and prerogatives, the municipality experienced a repressive campaign as the army returned to local politics, limiting the city’s room for maneuver.

The return of the army

Cheel Chowk Road. Karachi. by Ajmeri CC BY-SA 3.0

The military institution has always kept its eye on Karachi, the country’s economic and financial artery. Although it had not deployed troops in the city since its 1992-1994 containment of a budding civil war, it had not entirely disengaged, maintaining its presence via intermediaries: political parties, criminal groups and official security forces (the Sindh Rangers, led by military men).

Building on its presence in Karachi (where the army’s 5th corps is based), the army gradually increased its activities amid a new antiterrorist and anti-crime operation. In 2013, Nawaz Sharif’s new government ordered the Rangers and the police to reestablish order in the city. Over the months, this operation took on an increasingly pronounced anti-Muhajir Qaumi Movement turn: incarceration of its mayoral candidate, raids of its offices and arrests of its leaders and armed activists. Within several months the MQM was stripped of its threatening hegemon status and could not longer shape city life according to the whims of its volatile leadership.

All of these elements – political instability, the manipulation of institutions, the proliferation and entanglement of sources of violence, the ethnic dimension of conflicts and the national aspect of the issues, especially economic ones – consolidated Karachi’s reputation as an ungovernable megalopolis.

Governable disorder

Orangi, le plus grand quartier informel de Karachi, vu des collines de Nazimabad (2011) – Crédits : Laurent Gayer

Yet this apparent state of anarchy is misleading. The ambient disorder is more orderly than it appears. While no actor – neither the MQM nor the army – has succeeded in entirely controlling the situation, public disturbances follow regular temporal, spatial and strategic patterns (fights do not break out just anywhere, anytime and with whomever) that have allowed the population and economic actors to adapt to at least some degree. Thus, Karachi’s violent government does not result from strategic decisions – or even conspiracies – by the parties involved so much as from routinized violent interactions. It is precisely this normality of armed politics and of their attendant violent exchanges that the army, via the Rangers, has attacked over the past years. And it has been successful: the MQM was the first victim of this vast effort to demilitarize local politics, but no militia or criminal group was spared. The Lyari gangs and the Pakistani Taliban entrenched in several Pashtun neighborhoods were also brought into line by the Rangers.

An uncertain future

It is too early to speak of the demise of the MQM, which could recover at the ballot box, but it is clear that the party has significantly weakened. The MQM has lost its aura of invincibility and capacity to impose its will on the city’s population, beyond the Muhajir community. This situation has created a political vacuum that the army intends to fill by promoting its protégés. The Karachi government is certainly not close to conforming to Weber’s legal-rational model positing the supremacy of the law and the impersonal nature of relationships of power. For now, the armed policy of the 1984-2014 period appears to be in retreat, along with the myriad strongmen who had exploited the city in a bid to form a state for their benefit.

—–

* * The Sindhis form the majority of the population in the province of which Karachi is the capital: the Sindh. In contrast to the Urdu-speaking Muhjajir, they speak sindhi, which since the 1970s has had the status of official language in the province, just like Urdu.

** The Muhajir (from the Arab muhajir, meaning “refugee” or “migrant”) are the descendants of Urdu-speaking Muslims who left India after the 1947 partition. While these “migrants” came from various regions in India, they are now considered as their own ethnic group in Pakistan. The raison d’être of the Muhajir Qaumi Movement (MQM), founded in 1984, is to defend their interests.

Laurent Gayer, Karachi. Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City, Londres, Hurst, 2014.

Laurent Gayer, « The Need for Speed: Traffic Regulation and the Violent Fabric of Karachi » (pdf), Theory, Culture & Society, 33 (7-8), 2016.

Laurent Gayer, « Les Rangers du Pakistan : de la défense des frontières à la “protection” intérieure », in Jean-Louis Briquet et Gilles Favarel-Garrigues (dir.), Milieux criminels et pouvoir politique. Les ressorts illicites de l’État, Paris, Karthala, 2008.

Previous post: International migrations: metropolises, places of inclusion or drivers of exclusion? <-> Next post: The waste crisis and urban fabric in Beirut