Entrepreneurial Finance: Beyond People

18 December 2019

The 1980s Debt Crisis: the Players and the Archives

18 December 2019Returning to the Gold Standard in Great Britain After the Napoleonic Wars

Gold bars created by Agnico-Eagle. Crédits : domaine public

The gold standard (1)The gold standard is a monetary system in which the monetary unit is defined with reference to a fixed weight is one of the most important and controversial macroeconomic institutions in history. Half a century after its complete abandonment, its specter continues to haunt political circles across the world. Its supporters include the highest monetary authorities in the United States, to the dismay of macroeconomists. Proponents of the gold standard often cite its reestablishment in Great Britain after the Napoleonic Wars. It is cast as great political foresight that prevented ensuing governments from manipulating prices and the true value of public debt by creating money. Here, we show that the decision to return to the gold standard appears to have been motivated by the personal financial gains of influential members of the British government and parliament.

The context

Bataille de Trafalgar, 1805, par Auguste Étienne François Mayer. Domaine public

In 1815, the English and their allies won the Napoleonic wars. After twenty-two years of war, the country was in a difficult economic situation. The debt-to-GDP ratio reached 190%. Prices increased by 36%. In this context, the idea was to re-establish the gold standard suspended in 1797 in order to facilitate financing the war. This consisted of limiting the creation of currency, since the latter required a counterparty and a gold exchange guarantee. The goal was therefore to establish a fixed exchange rate between Bank of England banknotes and gold.

This decision went against the interests of taxpayers who bore the brunt of public debt. The return to the gold standard resulted in a significant drop in prices. This deflation (long-term decrease in the general price level) automatically increased the real cost of public debt. At the same time, the return to the gold standard guaranteed creditors repayment in a currency with stable purchasing power, since it was anchored to a fixed weight of gold. This strengthened the credibility of English public finances. It should be noted that during the war, traded public debt securities lost between 10% and 50% of their value. Restoring the gold standard, and thus returning to pre-war parity, significantly benefited public debt holders.

Crise de l’euro/Dette grecque. Crédits image : domaine public

Southern European countries faced a similar tradeoff during the sovereign debt crisis. These countries had very high debt-to-GDP ratios denominated in euros. For example, this ratio was 130% when the sovereign debt crisis broke out in Greece in 2009. In this situation, the choice was between maintaining a fixed exchange rate – between the drachma and the euro in the case of Greece – and reducing public debt by devaluing the currency.

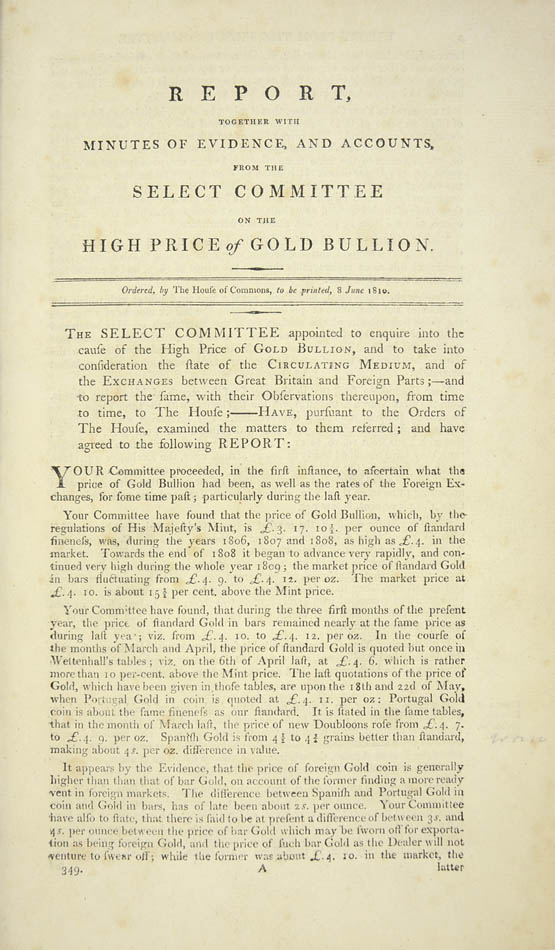

The controversy

House of Commons Select Committee reports on the price of gold bullion – 1810. Source : Shapero Rare Books

At the time, debates raged between recognized economists, investment bankers, and the public. David Ricardo believed that only a return to the gold standard would sufficiently restrain the Bank of England’s implementation of monetary policy. Others, such as Thomas Malthus, Nathan Rothschild and Alexander Baring, pointed to the negative effects of deflation on demand for goods and money and the payment system. Meanwhile, the public feared that tightening monetary conditions would further aggravate the postwar depression, and also opposed deflation. This translated into an avalanche of petitions to Parliament and riots. Yet a return to the gold standard was ratified in 1819. Disastrous consequences unfolded as anticipated (2)Hilton, Boyd – “Corn, Cash, Commerce”, page 77, 2000, Oxford University Press. The unemployment rate, which had hovered around 5% during the war, grew to 17% (3)Feinstein, Charles H. “Pessimism Perpetuated: Real Wages and the Standard of Living in Britain during and after the Industrial Revolution”, The Journal of Economic History, 1998. This decision was embraced to the detriment of the general economy and of the most disadvantaged people.

How to explain a decision that went against the collective interest?

Given the good economic reasons not to return to the gold standard, the era’s political dynamics might explain this decision. This is the hypothesis of Nobel prizewinner Douglass North and his co-author Barry Weingast. The two authors argue that a large majority of British parliamentarians held public debt. Guaranteeing the value of their financial assets required returning to the gold standard, thus precluding debt restructuring from the outset.

Based on Bank of England archival research, we show that the decision to return to the gold standard was motivated by the personal financial gains of some influential members of the British government and parliament. We tested this hypothesis by analyzing the public debt assets held by British parliamentarians in 1819, as recorded in the Bank of England’s archives. We undertook this analysis for around 70 members of the British Parliament, accounting for all the parliamentarians who spoke during the debates and deliberations on the bill to restore the gold standard (about 10% of all parliamentarians).

Potential conflicts of interest

It appears that virtually all the members of this sample (90%) held public debt. The amounts they held averaged £10,355, generating an annual interest rate payout of £310. In 1819, a farmworker earned an annual salary of £40, and a senior civil servant, £219 (4)Lindert, Peter R. and Jeffrey G. Williamson – “Pessimism Perpetuated: Real Wages and the Standard of Living in Britain during and after the Industrial Revolution“, 1983, Economic History Review. These amounts are also impressive when expressed in current values: a capital of £10,355 then is now equivalent to a fortune of £11.5 million (5)Measuring Worth – “Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present“, 2019. It is interesting to compare these amounts with parliamentarians’ political positions. The assets of parliamentarians who opposed the return to the gold standard totaled £8,117 on average, while those of parliamentarians who supported the return to the gold standard totaled £18,473 on average.

Ces montants sont également impressionnants lorsqu’exprimés en valeurs actuelles : un capital de £10.355 d’alors équivaut aujourd’hui à une fortune de £11.5 millions (6)Measuring Worth – “Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present“, 2019. Il est intéressant de rapprocher ces montants des positions prises par les parlementaires dans leurs positions politiques. Ainsi, les avoirs des parlementaires s’étant exprimés contre le retour à l’étalon-or sont en moyenne de £8.117 tandis que ceux des parlementaires favorables au retour à l’étalon-or s’élèvent en moyenne à £18.473 (7)Formal econometric tests corroborate that the two distributions are different.

House of Lords. 1809 . Crédits image : domaine public

The committees tasked with preparing the draft law in the House of Commons and the House of Lords included a significant number of influential politicians of a high status, including Prime Minister Liverpool (£35,815 of public debt), the Ministers of the Budget (Vansittart: £30,660), Foreign Affairs (Castlereagh: £40,446), Interior (Sidmouth: £5,750) and War and Colonies (Bathhurst: £12,776). The Speakers of the two Houses of Parliament were also involved –Castlereagh for the Municipalities, and Harrowby (£23,808) for the Lords. In total, only one of the 35 members of these two committees voted against returning to the gold standard. Thus, while our sample is small, its composition is likely to have greatly influenced the rest of the parliamentarians’ positions on returning to the gold standard.

What remains to be done

Given the amounts involved, potential conflicts of interest cannot be ruled out in the decision-making process leading to the return to the gold standard. The fact that parliamentarians in favor of returning to the gold standard held, on average, almost 2.5 times more public debt than opponents seems to confirm this. In order to make our initial results more robust, we are collecting additional data on the characteristics of parliamentarians, such as their party of affiliation, their overall wealth, their electoral district, and the level of competition they faced.

We underscored that our sample includes specific politicians. As a result, our sample may not be representative of parliamentarians as a whole. In order to address this potential problem, we are currently collecting information on the public debt held by all members of the British Parliament in 1819. This new database will be complemented with information on the characteristics of the aforementioned parliamentarians. This additional data will allow us to highlight possible regional and interparty disparities, as well as analyze whether greater electoral competition neutralized politicians’ conflicts of interest.

Finally, some questions remain about politicians’ motives for holding so much public debt. Was the idea to show that they were confident in a British victory? Or did they predict an appreciation of public debt throughout the war, by taking a gamble whose outcome they could influence? To understand their ultimate motives, we plan to examine the transactions that politicians made during the war, particularly those following military victories and defeats.

Pamfili Antipa is an economics researcher in the monetary policy studies and research department of the Bank of France, and associate researcher in Sciences Po’s Economics Department. Her research spans monetary economics and economic history. She especially focuses on the effects of monetary and budgetary policies on the sustainability of public finances from a historical perspective. See all her publications. Quoc-Anh Do is Associate Professor in Sciences Po’s Economics Department and the LIEPP (Laboratory for interdisciplinary evaluation of public policies). An expert in applied microeconomics, he focuses on political economy, the economy of social networks, as well as corruption and corporate governance. See all his publications.

Notes

| ↑1 | The gold standard is a monetary system in which the monetary unit is defined with reference to a fixed weight |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Hilton, Boyd – “Corn, Cash, Commerce”, page 77, 2000, Oxford University Press |

| ↑3 | Feinstein, Charles H. “Pessimism Perpetuated: Real Wages and the Standard of Living in Britain during and after the Industrial Revolution”, The Journal of Economic History, 1998 |

| ↑4 | Lindert, Peter R. and Jeffrey G. Williamson – “Pessimism Perpetuated: Real Wages and the Standard of Living in Britain during and after the Industrial Revolution“, 1983, Economic History Review |

| ↑5 | Measuring Worth – “Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present“, 2019 |

| ↑6 | Measuring Worth – “Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present“, 2019 |

| ↑7 | Formal econometric tests corroborate that the two distributions are different |