Marriage Migration: Female Paths

18 May 2020

Breastfeeding Policies Disconnected from Reality

18 May 2020by Émilie Biland-Curinier, CSO *

The women mobilised in the Yellow Vest movement rightly denounced the fact that many single mothers face major financial difficulties on a daily basis while raising their children. Yet women originate separation and divorce proceedings more often than men. The high rate of marital breakups provides evidence of their appropriation of this individual right in a relatively recent context of legal equality with men. However, this major social change has not led to the equalization of conditions nor to the disruption of the gender order. Here is a look back at a key victory for women that is still far from enabling their emancipation.

The right to divorce is a key victory for women

© Gwydion M Williams. CC BY 2.0

In the second half of the 19th century, as in the 1960s and 1970s, reforms authorising and then facilitating divorce took place during periods of strong feminist mobilisation(1)Michèle Riot-Sarcey, Histoire du féminisme, La Découverte, 2015. Marriage was a patriarchal institution par excellence, and divorce, a means – albeit a regularly condemned one – of escaping the minorisation of women, which was enshrined in the Civil Code from 1804 until the mid-20th century. When divorce by mutual consent was instituted in France in 1975, it had been only ten years since married women had been able to open a bank account, sign an employment contract, and manage their personal property without their husbands’ consent. They had only gained parental authority over their children – previously reserved for “family heads ” – in 1970. In this sense, the right to divorce was part of a long movement towards equal rights between women and men and the recognition of individual rights in the private sphere.

Divorces started increasing in the mid-1960s, with the increase accelerating in the mid-1970s and continuing for thirty years(2)123 500 divorces en 2014. Des divorces en légère baisse depuis 2010, Insee, 2016. The increase roughly matched that of the share of women in the labor market: at the beginning of the 1960s, 40% of women between the ages of 30 and 50 were part of the labor force, versus 80% today(3)Forte hausse du taux d’activité des femmes en 50 ans, Insee, 2013. The principle of equal pay for male and female workers was enshrined in the Labor Code in 1972, reflecting the legal equality of spouses established seven years earlier. Changes in the labor market and private sphere thus combined to give women greater autonomy. In concrete terms, it is because they work outside the home that many women dare to break up with their spouses. Conversely, separation forces the women who interrupted their career to care for their children and support their husbands’ careers, to get a job.

Living with a man and having children always weaken the status of women

Bulgarian poster – Open Your Eyes: A campaign against gender violence. © Denitza Tchacarova / CC BY-SA

Today, the option of separation is crucial, if not vital, for some women. Heterosexual marriage remains marked by systemic violence. The survey on “Violence and gender relations”, conducted by the National Institute of Demographic Studies, estimated that 285 000 women were victims of physical and/or sexual assaults by their (ex-)partners in 2015e(4)Enquête Virage et premiers résultats sur les violences sexuelles – Documents de travail, – Ined éditions, 2017. Three years later, the Ministry of the Interior recorded 149 “domestic violence deaths”: men committed 80% of these homicides, while half of the female perpetrators had already been victims of spousal violence(5)Étude nationale relative aux morts violentes au sein du couple, Ministère de l’intérieur, 2019.

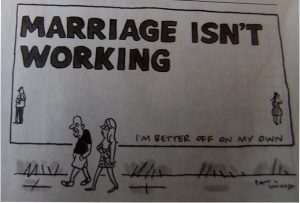

Beyond the violence, the 3,000 court files that I reviewed with other members of the Justines research team show that women are twice as likely as men to initiate separation proceedings initiated by only one of the spouses. Sociologist François de Singly explains that this discrepancy is attributable to many women’s dissatisfaction with their conjugal life. The women most dedicated to their homes object to their “marital confinement”, as opposed to their spouse’s autonomy. Others see marital life as an obstacle to their personal development, while a third group of women, in between these two camps, find that their aspirations gradually diverge from those of their partners. In all cases, de Singly argues that these women’s stories carry a “hymn to liberation”, and that separation is experienced as “regaining oneself”. Anne Revillard has shown that state feminists, be they elected officials or senior civil servants, have supported declining financial solidarity between former spouses (child support, spouse alimony) in the name of the recovered independence thanks to the separation. (6)When the state champions the cause of women. A historical perspective, Cogito, 2017.

Crédits image : Ryan McGuire , Pixabay

This underinvestment in the economic implications of separations is, however, problematic given the structural inequalities between women and men(7)Le temps domestique et parental des hommes et des femmes : quels facteurs d’évolutions en 25 ans ? − Économie et Statistique, Insee, 2015. Beginning in the 1970s, materialist feminist sociology highlighted the exploitation of women by men in marriage via domestic work, which is both unpaid and invisible. Women spend three hours a day on domestic work, versus two hours for men.

Being a mother continues to hold back careers, while fatherhood is an accelerator(8)Entreprises, enfants : quels rôles dans les inégalités salariales entre femmes et hommes, Insee, 2019. Ending a marriage may well reflect the often-disappointed aspiration for equality between intimate partners revealing a divergence in female and male conditions due to the gendered division of professional and domestic work.

Separations do not free people from gender inequalities

Therefore, ending marriages has not, any more than entering marriages, changed gender relations. As sociologist Christine Delphy highlighted in 1974, “some aspects of the state of marriage (…) are perpetuated in the state of divorce,” with “differential obligations for husband and wife” continuing beyond life together. If women’s emancipation is defined as their ability to free themselves from the servitudes associated with their gender – among which violence and economic disadvantage rank first – or from gender roles (starting with motherhood), then the current regulation of marital separation falls very short.

1 in 3 women worldwide have experienced physical and/or sexual violence, mostly by an intimate partner – WHO

First, separation does not always suffice to end intimate partner violence. The rejection of separation is a recurring motive for men who kill their spouse(9)Étude nationale relative aux morts violentes au sein du couple, Ministère de l’intérieur, 2019. Since the 2000s, in response to feminist demands, several measures have been implemented to keep violent spouses away. However, judges are reluctant to use them, as shown in research from Solenne Jouanneau and her team on protection orders(10)Violences conjugales et Protection des victimes. Usages et condition d’application dans les tribunaux français des mesures judiciaires de protection des victimes de violences au sein du couple, Mission de recherche Droit et Justice, 2017-2019. Meanwhile, in her study on police work addressing charges between intimate partners, Marine Delaunay found that women are frequently suspected of using violence to gain custody of children – a suspicion that hinders criminal prosecution(11)Violences conjugales et Protection des victimes. Usages et condition d’application dans les tribunaux français des mesures judiciaires de protection des victimes de violences au sein du couple, Mission de recherche Droits et Justice, 2017-2019.

Second, women become poorer than men after separations. According to tax data, divorce leads to a 19% average loss of standard of living, compared to a 2.5% loss for men(12)Les conditions de vie des enfants après le divorce, Insee, 2015. Here again, public authorities have taken action. Since the 1970s, single-parent families (84% of which consist of a woman and her child or children) have been among the priority recipients of public redistribution(13)Ménages – Familles − Tableaux de l’économie française, Insee, 2019. Before redistribution, the poverty rate for women raising two children alone is 60%. It falls to 40% after redistribution(14)Les effets des transferts sociaux et fiscaux sur la pauvreté monétaire, DREES, 2019. But this “partial transformation of private patriarchy into public patriarchy” – in the words of the philosopher Diane Lamoureux – is based on a regime of assistance and protection. It places women in the position of claimants, rather than people with autonomous rights. It leads administrations to monitor their intimate lives (are they back in a relationship?) and to supervise their parenting practices through “support for parenthood” measures, in addition to older forms of intervention, through social work and juvenile justice.

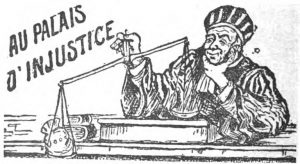

An unaware justice system

“At the Palace of Injustice”, vignette extracted from the French Magaine “Père Peinard”, 1894, public domain

Marital separation professionals, starting with judges, lawyers, and notaries, are actually relatively unaware of these unequal dynamics. They pay little attention to child support payments, and only minimally consider women’s career sacrifices. Moreover, matrimonial law remains blind to the rights of the increasingly large number of unmarried spouses. As sociologists Céline Bessière and Sibylle Gollac underscore, these lawyers partake in “sexist accounting” that disadvantages women and leads to significant wealth inequalities. Moreover, by favoring an amicable and peaceful settlement of separations, current policies overlook marital asymmetries and power relations. The lack of time and resources in the courts is conducive to maintaining the status quo and, thereby the perpetuation of the gendered division of labor forged during life together. The delegation of a portion of family cases to lawyers also risks weakening the position of women. Since they are financially less well off, women find it more difficult to hire the lawyers who have the greatest expertise in these issues.

Manifestation le 8 mars 2017 Paris. Crédits image : Jeanne Menjoulet. CC BY-ND 2.0

Marital separations thus fall far short of ending gender-based statutory and identity attributions. In most cases, the mother takes care of the children on a daily basis, while the father takes care of them episodically and contributes financially by paying alimony(15)Les décisions des juges concernant les enfants de parents séparés ont fortement évolué dans les années 2000, Ministère de la justice, 2015. The hierarchical dualism between men and women is thus confirmed and even amplified in the aftermath of a breakup. Of course, the norm of “co-parenting”, which is highly prevalent in professional and public discourse, values the involvement of both parents with their children. But in the working classes, the precariousness of the labor market and the cost of housing reinforce the division of parental roles. These blue-collar male workers, who often have temporary or fixed-term contracts, staggered working hours, or are unemployed, are less able to assume their parental role and receive less support from legal professionals. In the middle and upper classes, shared physical custody is more common, but differences in paternal and maternal obligations remain: fathers are encouraged (but not required) to look after their children; mothers must grant the father a role if he asks for one, but must continue to mostly if not completely shoulder responsibility themselves if he does not.

This is the conclusion of my book Gouverner la vie privée [Governing Intimacy in France and Quebec. How Judicial Policies Shape Inequalities after Divorce], which compares the institutional production of family inequalities in France and Canada. In marital separations, as in many other areas, individual freedoms and equal rights are necessary but insufficient conditions to meeting individual and collective aspirations. If inequalities of status are not truly challenged, and if intimate relationships and parental roles are not deeply transformed, this emancipatory drive will remain unfinished for a long time.

Sociologist and political scientist Emilie Biland-Curiner is a full professor at the Center for the Sociology of Organisations. She studies how law and public policy shape individuals’ private life (through parental roles) and professional life (in the civil service), and how they help differentiate and hierarchise social statuses according to class, gender, sexuality, and race. She is a member of the Institut Universitaire de France and is currently working on LGBTQ parents’ experiences of law, rights and courts in France, Canada, and Chile. See her publications.

Translated from French by Carolyn Avery

Notes