The Littoral: A Historical Investigation in the Anthropocene Epoch

3 July 2020

Pesticides. How to Ignore What We Know

3 July 2020

Action against air pollution, Paris, June 2013. © Friends of the Earth CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

By Sylvain Parasie, médialab*

Some environmental activists and scientists have described the current boom in digital air pollution sensors as a “changing paradigm”(1)Snyder, E. G., Watkins, T. H., Solomon, P. A., Thoma, E. D., Williams, R. W., Hagler, G. S., & Preuss, P. W. “The Changing Paradigm of Air Pollution Monitoring”, Environmental Science & Technology, 2013..

For a hundred euros, a small box can be purchased that measures in real time the pollutants in the air we breathe (particles, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, etc.). The proliferation of micro-sensors would create a radical shift in official air quality monitoring, which in most Western countries relies on a small number of stations that are heavy, costly and scattered throughout the country. First, by making pollution visible on a balcony, in the street or in a neighborhood – i.e. on a scale that previously eluded monitoring institutions. The air that people breathe would be better known and the sources of pollution more identifiable. Then, by providing people with digital tools (such as smartphone or tablet apps) in order to investigate for themselves the air they breathe and protect themselves by adapting their behavior or informing the authorities.

Mobile air quality monitoring station of the Airaq association, in Mussidan, © Cjp24 – CC BY-SA 4.0

However, the gap between institutions and citizens is so great that incorporating these sensors into air pollution monitoring is not straightforward at all. On the one hand, monitoring institutions and environmental scientists have expressed strong doubts about the quality of the sensors available on the market and questioned the accuracy of their measurements. The sensors are often not certified and follow specifications that are too far from the metrological requirements of monitoring institutions(2)Lewis, A. & Edwards, P. – “Validate Personal Air-Pollution Sensors”, Nature News, 2016.. On the other hand, mobilisations have long been highly critical of the way in which institutions assess environmental damage; in particular, because official measurements are not intended to identify pollution peaks, only to make sure – on average and over an extended period – that levels of certain pollutants do not exceed the thresholds set by law(3) Ottinger, G. -“Buckets of Resistance: Standards and the Effectiveness of Citizen Science”, Science, Technology, & Human Values, 2010..

In this context, how can small digital sensors provide a forum for collaboration between activists and institutions? What is the process through which citizen pollution measurements may be deemed credible by official authorities, when they are not even in compliance with metrological standards? To answer these as yet little studied questions(4)With the exception of Jennifer Gabrys’ work. See J. Gabrys and H. Pritchard – “Just Good Enough Data and Environmental Sensing: Moving Beyond Regulatory Benchmarks toward Citizen Action ”, International Journal of Spatial Data Infrastructures Research, 2018..

Sylvain Parasie (médialab, Sciences Po) and François Dedieu (LISIS) carried out an investigation in California, a state at the forefront of environmental regulation. In the spring of 2017, they followed three associations that have developed sensors whose measurements are now partly recognised by the California Environmental Protection Agency (CalEPA). By interviewing activists and official representatives, as well as epidemiologists and researchers involved in developing these infrastructures, Sylvain Parasie and François Dedieu wanted to understand how citizen measurements came to be recognised as credible by official authorities.

Sensors as Tools of Governance

The study showed how political and scientific dynamics have led actors working within California institutions to take an interest in the measurements produced by citizen sensors and to consider them as tools of knowledge and governance. The rise of “environmental justice” as a legal and political principle since the early 2000s has played a major role. Enshrined in California law, this principle requires authorities to focus first and foremost on environmental damage suffered by socioeconomically disadvantaged populations. It is in this context that certain members of CalEPA have championed the idea that citizen sensors would complement the official monitoring network through increased visibility regarding the quality of the air breathed by the most vulnerable groups.

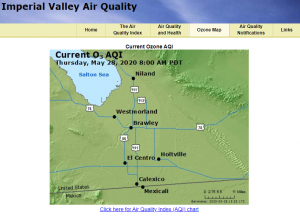

Citizen air pollution monitoring program by the “Civic Committee of the Valle, Inc.” © All rights reserved

The rise of exposure science has also contributed to making sensors more appealing to environmental monitoring institutions. This field of research strives to assess the real conditions in which individuals are exposed to pollutants (5)Jean-Noël Jouzel – “L’usage contrôlé des pesticides. Sociologie d’un mythe d’action publique”, habilitation to supervise research in Sociology, 2018, Sciences Po.

Practical and regulatory in nature, exposure science has established itself as the missing link between the environmental sciences, which analyse the diffusion of pollutants in physical environments (air, water, earth), and epidemiology, which studies the effects of pollutants on large populations over the long term. Advocates of exposure science argue that real protection of the population requires measuring the intensity and duration of contact with toxic agents present in the environment. Hence their interest in sensors that measure the local pollution variability.

Negotiating Infrastructure

Beyond these trends, however, the study shows the importance of the process involved in establishing the rules that govern the deployment of the sensor infrastructure. In order for citizen measurements to be deemed credible by official authorities, while remaining acceptable to activists, a set of rules had to be drawn up on three different levels: (1) calibrating the sensors; (2) choosing their location; (3) dividing up the work of data monitoring and device maintenance. At every level, this meant establishing rules to reduce tensions between the actors involved.

The project implemented in Imperial County is particularly enlightening. Located along the Mexican border 200 km from San Diego, Imperial County experiences significant pollution related to agricultural activities. From its inception, the infrastructure project involved not only residents of the county, but also epidemiologists, researchers and supervisory authorities, who provided them with cognitive, material and financial support.

Calibrating to Engage the Authorities

The first phase involved calibration. To convince official authorities of the robustness of the measurements produced by citizen sensors, researchers in environmental sciences at the University of Washington systematically compared measurements produced by official stations and those from citizen sensors. After testing a sample of commercially available micro-sensors in a laboratory, the University of Washington team selected the most suitable ones and combined them in a versatile device; this prototype was then installed in an official county station to calibrate it according to local humidity and temperature conditions. Statistical models were created from the two sets of measurements to correct all the data produced in Imperial County by citizen sensors once they were permanently installed on roofs or in residential gardens.

Arbitrating Between Territorial Expertise

Diagram of citizen air quality measurement infrastructure in Imperial

The second phase involved choosing the location of the sensors. It pitted local activists against epidemiologists. On the one hand, environmental activists sought to validate the expertise of the inhabitants, who knew where the most vulnerable among the population lived, how they moved around town, and which neighbors would allow a sensor to be installed on their roof. On the other hand, the epidemiologists highlighted their own expertise, based on statistical modeling, to define optimal locations given the specifics of the territory. Specialists in community health outreach acted as mediators, helping local activists to involve the inhabitants in choosing locations for half of the sensors, while the epidemiologists chose where the remaining citizen sensors were placed.

Dividing Up Maintenance Work

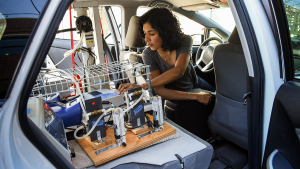

Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (univ. of Washington) student Magali Blanco checks mobile monitoring equipment. © Sarah Fish.

The last phase consisted in dividing up the work of device maintenance among the actors. In Imperial County, the activists own the infrastructure – the sensors, servers and website that broadcast pollution measurements –, but the University of Washington epidemiologists are the ones who transform the data into pollution measurements and oversee daily data monitoring. At the time of the study, however, the division of maintenance work remained debatable. It was not clear whether local activists could secure the human and material resources required for daily data monitoring.

The case of California shows that installing digital micro-sensors alone cannot transform how air pollution is monitored. The credibility of citizen measurements is a central issue, one that appears to be both the result of political and scientific dynamics, as well as the way in which the measurement infrastructure is designed to reduce tensions among the actors involved. The social sciences therefore have an important role to play in identifying new forms of asymmetry and cooperation that are liable to emerge in specific political, scientific and institutional contexts.

Translated by William Snow

Sylvain Parasie is a professor of sociology in the Sciences Po médialab. Since 2010 his work has focused on how digital technologies are transforming the way we learn, debate and engage in the public arena. François Dedieu is a sociologist at the Institut national de recherche pour l’agriculture, l’alimentation et l’environnement (INRAE). His research focuses on the relationship between organisations and the production of knowledge in the area of risk.

Parasie Sylvain, Dedieu François – À quoi tient la crédibilité des données citoyennes ? L’institutionnalisation des capteurs citoyens de pollution de l’air en Californie, Revue d’anthropologie des connaissances, avril 2019.

Notes

| ↑1 | Snyder, E. G., Watkins, T. H., Solomon, P. A., Thoma, E. D., Williams, R. W., Hagler, G. S., & Preuss, P. W. “The Changing Paradigm of Air Pollution Monitoring”, Environmental Science & Technology, 2013. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Lewis, A. & Edwards, P. – “Validate Personal Air-Pollution Sensors”, Nature News, 2016. |

| ↑3 | Ottinger, G. -“Buckets of Resistance: Standards and the Effectiveness of Citizen Science”, Science, Technology, & Human Values, 2010. |

| ↑4 | With the exception of Jennifer Gabrys’ work. See J. Gabrys and H. Pritchard – “Just Good Enough Data and Environmental Sensing: Moving Beyond Regulatory Benchmarks toward Citizen Action ”, International Journal of Spatial Data Infrastructures Research, 2018. |

| ↑5 | Jean-Noël Jouzel – “L’usage contrôlé des pesticides. Sociologie d’un mythe d’action publique”, habilitation to supervise research in Sociology, 2018, Sciences Po |