Populism: Research Directory

17 May 2021

Politics of Ethnicity and Democratic Resilience

17 May 2021

Capitol Stormed Jan 6, 2021 © CC BY-NC 2.0, Blink O’fanaye via Flickr

The storming of the Capitol on 6 January 2021 by Donald Trump’s supporters provided surreal images to illustrate the ‘wave of populism’ that has been widely castigated in recent years. Without the Covid crisis and its catastrophic management, the 45th President of the United States, would probably have been re-elected.

The USA is not alone: over the past decade, right-wing populism appears to be gaining ground, slowly but surely, in all western democracies. In 2019, the success of Vox, Spain’s extreme right-wing party, marked the end of Spain’s ‘immunity’ to this wave. Poland and Ireland are the only countries today in western Europe with no significant right-wing populist party.

It’s the Economy, Stupid!

Multiple economic, cultural and psychological reasons have been proposed to explain the recurrent electoral successes of these currents. Herein, we will just be looking at the economic foundations of such votes. Many people believe that the link with the economic difficulties and the 2008 crisis is self-evident. Unemployment, poverty and growing inequalities are often cited to explain these protest votes. This article aims to demonstrate the inadequacy of these factors and to propose alternative explanations. The left-wing populist vote will not be considered because of the different motivations and sociological composition of the two electorates (only 12% of Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s(1)Jean-Luc Mélenchon, born 19 August 1951, candidate for 2017 presidential election. He founded the far-left movement La France Insoumise (FI, “France Unbowed” voters voted for Marine Le Pen(2)Marine Le Pen, born 5 August 1968, President of the National Rally (previously the National Front) since 2011. in the second round of the French presidential election in 2017).

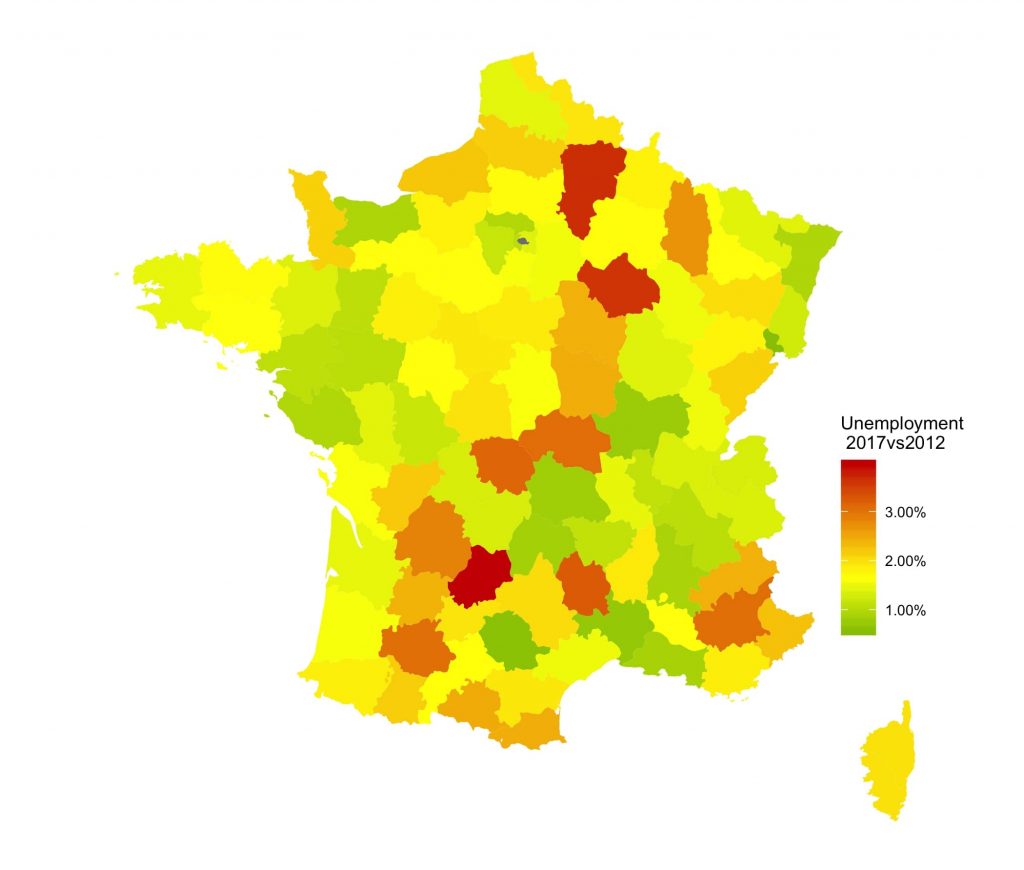

Source: Insee data. © Alexis Baudour, Sciences Po

Unemployment: a Scapegoat

Unemployment appears to be the mostly given common reason for the populist vote. In France, unemployment has been proposed systematically since the 1980s as the reason for the electoral performance of the extreme right-wing party led by Jean-Marie Le Pen, and then his daughter Marine. However, when local employment figures are placed alongside election results, the link is far from obvious. Figure 1 shows the map of unemployment figures in all French departments from 2012 to 2017. Figure 2 shows the geographic distribution of the increase in votes for Le Pen in the first round of the presidential elections from 2012 to 2017. There is no apparent correlation between the two. The impressive progression of Marine Le Pen in the north and, to a lesser extent, in the north-east and south, appears to be unrelated to trends in unemployment figures. Furthermore, the unemployed are no more tempted to vote for Le Pen than other voters, according to 2017 surveys(3)Florent Gougou, Nicolas Sauger. “The 2017 French Election Study’ (FES 2017): a post-electoral cross-sectional survey.” French Politics, 2017. (bearing in mind other factors, such as the level of qualification).

Does the specific case of this election illustrate a generality? It appears so. The multiple research projects that have attempted to establish a link between unemployment and the radical right wing generally fail to show a clear effect. One result confirmed by the Abdelkarim Amengay studies(4)Amengay, Abdelkarim and Daniel Stockemer. ‘The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Meta-Analysis of Structural Factors.’ Political Studies Review, 2018., which reviewed 50 studies on the topic, reported the absence of any statistical relationship between unemployment and the populist vote.

Source: Insee data. © Alexis Baudour, Sciences Po

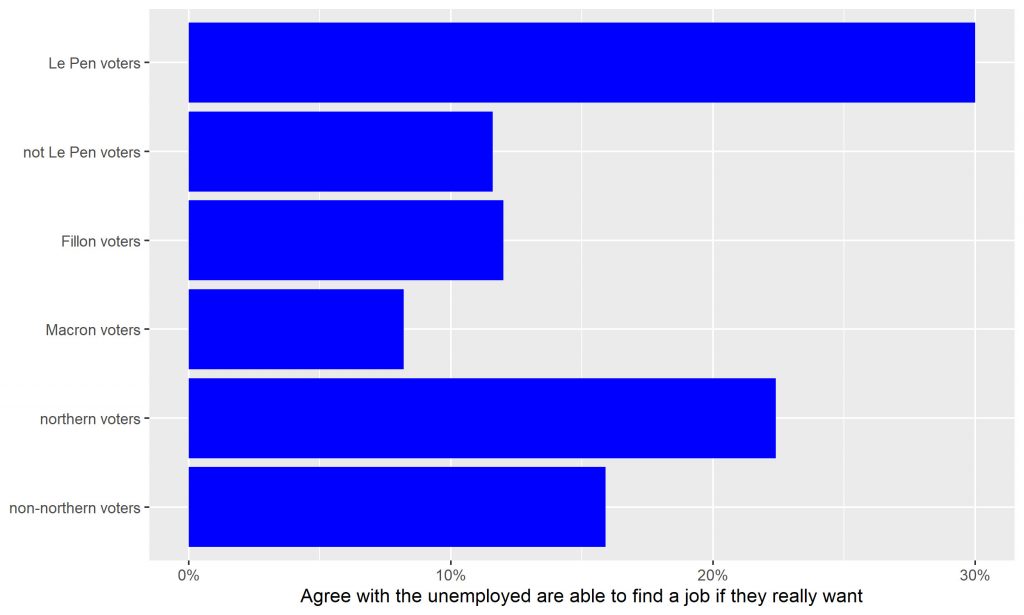

Some researchers have suggested that the effect is conditional, with unemployment encouraging the populist right-wing vote in regions with high immigration, for example. This variant is not conclusive either, particularly in France, where the Front National (now the Rassemblement National) has been successful in regions with low immigrant populations. Although there is no simple, direct link between unemployment and voting for this party, there are other interesting aspects to be considered. Figure 3 shows that 30% of Le Pen’s voters claimed to ‘fully agree’ with the statement ‘the unemployed could find work if they really wanted to’, i.e. a proportion 3 times higher than among the electorate of François Fillon (5)François Fillon, born 4 March 1954, a retired politician who served as Prime Minister of France from 2007 to 2012. He was the nominee of the Republicans (centre-right political party), for the 2017 presidential election., traditional right-wing party candidate at the time of the survey or Emmanuel Macron. Yet FN voters, in spite of not being privileged themselves, bear judgement on the unemployed and do their best to distance themselves from this population. For example, the population of northern France, a particularly poor region, in which support for Marine Le Pen progressed significantly in 2017 (figure 2), is also particularly hostile to these job-seekers (22% compared with 15.5% in the rest of France, figure 3). In general, populist voters in many countries are critical of the populations receiving social benefits, even in countries where they are relatively few.

Source : French Election Study 2017. © Alexis Baudour, Sciences Po

We should perhaps try to understand this recrimination against the poorest by the almost poor. In terms of income, they are just one step higher than the unemployed; their hostility towards this category could therefore indicate a desire to distinguish themselves from the latter, i.e. establishing a symbolic distance to avoid any confusion between the two groups.

Poverty: Populism?

To examine the possible explanation of poverty and rich-poor inequalities, I am investigating European countries in which right-wing populism is firmly established, thus excluding those countries in which populism is a recent and unstable trend, such as the UK (where the Brexit party/UKIP only achieved 2% in the recent elections). I am therefore concentrating on the places where the radical right wing has been a significant political player for 30 or 40 years, i.e. Austria, Switzerland, France, Denmark, Flanders and northern Italy. These countries are clearly wealthier than the European average and rich-poor inequalities are more obvious there than in Spain or the UK, for example.

Generally speaking, explaining the populist vote by poverty comes up against the ‘wealth paradox’ concept introduced by Mols and Jetten(6)Mols, Frank and Jetten, Jolanda. ‘The Wealth Paradox: Economic Prosperity and the Hardening of Attitudes’. Cambridge University Press, 2016.: electoral success for populism does not come during crises, but often during periods of economic recovery several years after the actual crisis. Brexit (2016), Trump’s victory (2016), the rise of the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party in Germany (2017), Vox in Spain (2019) and the Danish People’s Party in Denmark (2015) all occurred during recovery periods. Older breakthroughs in France, in the Netherlands in 2002 or in Australia in 1998 also appear to confirm this pattern (other examples are also found in eastern European countries, such as Poland). Since poverty decreases during these more opulent periods of economic recovery, it is difficult to consider it as a likely explanation for the radical right vote.

A Danish People’s Party’s Citroën car, with the portrait of his leader Kristian Thuelesen Dahl. “More Denmark, less EU” “it is possible”. Christiansborg, Copenhagen, Denmark © Jebulon, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Growing inequalities between rich and poor do not seem to offer a plausible explanation either. The figures are unequivocal: large, cosmopolitan cities, like Paris and London, where the gap between rich and poor residents is most spectacular, are resistant to the extreme right. In fact, Marine Le Pen obtained just 4.5% of votes in Paris (a score that has been declining with every election for the past 30 years, in opposition to the results for the rest of France). The other European capitals – where the inequality reference coefficient (Gini) is also high – are equally resistant to the radical right wing.

Populism in Northern France

However, another form of economic inequality is clearly more closely related to the FN vote: if we look at the cities in which votes for Le Pen increased by 13 points or more between 2012 and 2017, these 53 cities are in northern France (not surprisingly, considering Figure 2). However, median income (the income amount that divides the population between those whose income is higher and those whose income is lower) grew more quickly (8%) in these cities than in the rest of France (7%). On the contrary, the income in the first decile (income of the poorest 10%) declined sharply (-3%) in these cities, while it stagnated (5%) elsewhere in France. These cities, where FN made very significant progress, are characterised not by falling income among the middle class, but by the divergence between the working classes and the lower-middle classes and a rising middle class.

© Shutterstock

The increase in votes for the radical right wing is not a direct result of rising unemployment, poverty or inequalities. Understanding the relational dynamics between social groups that diverge economically, i.e. who are the winners and who are the losers, appears to be a promising lead. By crossing the data, it appears that votes for Le Pen could be related to an economic decline among the lower-middle classes, which become ‘tired of waiting their turn’ to achieve social recognition(7)Arlie Russell Hochschild, ‘Strangers in Their Own Land. Anger and Mourning on the American Right’, The New Press, 2016.. These people are anxious about a fall that would widen the gap with the established middle class, bringing them symbolically closer to the unemployed and excluded populations from which they are desperately trying to distinguish themselves. The confusion between unemployed and immigrants could also be due to this distancing effort.

Alexis Baudour, doctoral fellow at MaxPo, PhD in mathematics, is studying the influence of economic factors on the right-wing populist vote in Europe. The factors considered are evolution in unemployment, median income and inequalities. He uses longitudinal statistical methods to compare changes in income distribution with the results of successive elections.

Notes

| ↑1 | Jean-Luc Mélenchon, born 19 August 1951, candidate for 2017 presidential election. He founded the far-left movement La France Insoumise (FI, “France Unbowed” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Marine Le Pen, born 5 August 1968, President of the National Rally (previously the National Front) since 2011. |

| ↑3 | Florent Gougou, Nicolas Sauger. “The 2017 French Election Study’ (FES 2017): a post-electoral cross-sectional survey.” French Politics, 2017. |

| ↑4 | Amengay, Abdelkarim and Daniel Stockemer. ‘The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Meta-Analysis of Structural Factors.’ Political Studies Review, 2018. |

| ↑5 | François Fillon, born 4 March 1954, a retired politician who served as Prime Minister of France from 2007 to 2012. He was the nominee of the Republicans (centre-right political party), for the 2017 presidential election., traditional right-wing party candidate at the time of the survey |

| ↑6 | Mols, Frank and Jetten, Jolanda. ‘The Wealth Paradox: Economic Prosperity and the Hardening of Attitudes’. Cambridge University Press, 2016. |

| ↑7 | Arlie Russell Hochschild, ‘Strangers in Their Own Land. Anger and Mourning on the American Right’, The New Press, 2016. |