How Private International Law Reveals our Relationship to the Other

3 July 2020

Pollution Sensors: A Tool for Collaboration Between Citizens and Public Authorities?

3 July 2020The Coastal Environment: a Forgotten Player

by Giacomo Parrinello, Center for History*

Earth by night, seen from the satellite Suomi © Nasa, 2000

Coastal zones today are home to more than half of the world’s population(1)Christopher Small and Robert J. Nicholls, ‘A Global Analysis of Human Settlement in Coastal Zones’, Journal of Coastal Research, 2003., as well as big port cities, major tourist regions, and strategic industrial zones. This is the result of a history that we think we know well: that of modernization, industrial progress, urbanization, and the gradual emergence of a society of leisure and mass tourism. Yet it is an incomplete history in which a major player is always forgotten: the coastal environment. The MEDCOAST project led by the multinational team of the IDEX Chair in Environmental History that I have chaired has placed this player at the heart of the historical study(2) The investigation continues today with the project “Shifting Shores: An Environmental History of Morphological Change in Mediterranean River Deltas over the 20th century” funded by the City of Paris with an“Emergences” research grant..

Today we cannot afford this oversight to continue. These coastal areas where people live, work, and relax are now directly threatened by the consequences of climate change, starting with the sea level rise and coastal erosion. In some regions of the world, authorities have already prepared what in France is known as a “strategic retreat”, i.e. the abandonment of coastal infrastructures and localities deemed impossible or too costly to defend. Areas where it will still be possible to maintain a strong coastal human presence will require massive investments, as well as new forms of radical adaptation to instability.

Stabilising a Dynamic Environment

While the dynamism and instability of coastal environments are not new, the vulnerability they experience today is very recent. As highly dynamic spaces, shaped and reshaped by marine currents, by the transportation of sediment, and by winds and rivers, littorals have always been inhabited and shaped by people. They were inhabited, but unlike today, the human presence was mobile, limited, and most often adapted to the instability of coastal environments.

Cyprus © Dimitri Svetsikas Pixabay License

As extraordinarily productive and species-rich frontier ecosystems, littorals have been exploited by activities that took advantage of their intrinsic dynamism: small-scale fishing, hunting, shellfish farming, and non-intensive forms of agriculture and breeding. It was only at the beginning of the 19th century that urban, economic and demographic growth began and fueled the expansion of populations on the coasts beyond the historical boundaries of port cities. This is also the time when a variety of historical actors converged in the attempt to transform dynamic and changing coastal environments into a stable and stabilised line, into developed spaces.

To what end? What did modern actors seek to develop on the marine coasts? Which actors and what needs pushed for the stabilisation of these dynamic environments? How did these dynamic environments suffer or react, and what were the social and political consequences? Answering these questions requires looking at various phenomena such as tourism and urbanisation, industrialisation and fisheries, and globalised trade and transportation networks, while recognising the central issue that these processes and actors have shared: their location and their interactions with the littoral. From the perspective of the coastal environment, another history of modernisation could be written.

The Coastal Transition in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean, and especially its northwestern area, is emblematic of this transition, and the focus of our investigation. It is indeed an area that is highly representative of the diversity and morphological and ecological richness of Mediterranean coastal environments. In Liguria and on the French Riviera, cliffs and rocks steeply sloping down to the sea are punctuated by coastal plains where picturesque villages and important cities are ensconced between the sea and the mountains. Marseille is on the border between these ranges and the great swampy plains of the Rhone delta and Languedoc-Roussillon. In Catalonia, the Costa Brava range and coastal hills alternate with the wetlands of the Empordà and the deltas of the Llobregat and Ebro rivers. These territories are subject to a variety of influences and have distinct characteristics. But they all share the marine and terrestrial interactions and the dynamism and instability of coastal environments. They have all been profoundly reshaped and are now experiencing growing risks.

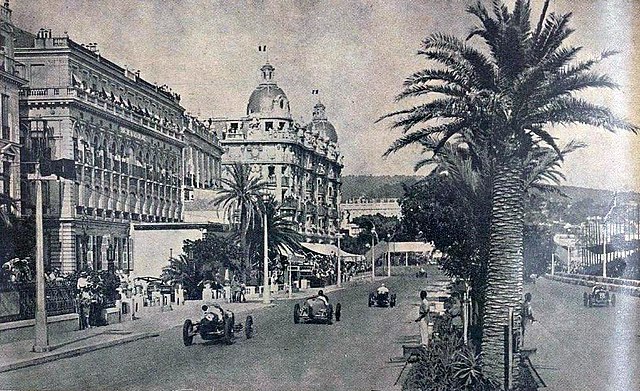

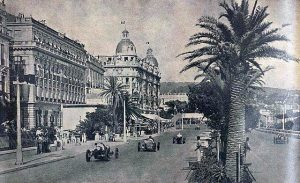

Nice Grand Prix of 1934 on the Promenade des Anglais – Public domain, Wikipedia

At the beginning of the 19th century, entrepreneurs and doctors established the first bathing establishments in these places to treat Northern European patients with sunbathing and seawater. Later, towards the end of the century, it was between the two Italian and French rivieras that the first forms of elite tourism were developed. At the same time, the textile, chemical, and steel industries permanently settled in the vicinity of Marseille, Genoa, Barcelona, and Tarragona, creating the first coastal industrial zones. These cities, and many others, expanded, incorporating agricultural land and villages along the coasts to create new districts and make way for railway lines, stations and, above all, increasingly invasive ports to receive and distribute materials and goods from all over the world. These processes accelerated after World War II, and the littoral is now home to an urban population of tens of millions of people. Deeply transformed by massive development, the northwestern coast has become the most polluted part of the Mediterranean basin.

The Uses of the Coast

Not all the actors in these transformations were pursuing the same objective. Industrialists were looking for quick and easy connections with the global flows of goods and raw materials, as well as opportunities to dump the toxic waste of their production directly into the sea at low to nor costs.

La Grande Motte ©Jjoulie, Wikipédia

Investors in seaside tourism, as well as the wealthy visitors and later the middle and working classes, were looking for the sun and the sea; as a source of profit for the former, and of health and entertainment for the latter. Cities were looking for areas to make way for a growing population, for energy, transportation, and sanitation infrastructures and networks, and to relocate industrial activities. Despite this diverse range of goals, from the 19th century onwards, transport networks and the flow of people, goods, and capital enabled all these actors to invest in the coasts with increasing intensity and scale, and all contributed to the great modern project of stabilising and developing the littoral.

Despite this convergence, sharing of the same coastal environment was a source of conflict. These conflicts often opposed old and new uses, such as the dumping of urban and industrial waste, which hindered seaside tourism, and industry, which thwarted traditional fisheries and coastal agriculture. For a long time, these conflicts remained limited to the local or regional level. But beginning in the second half of the 20th century, the acceleration of human colonisation of the coast and of its environmental consequences led to a growing number of antagonisms, accompanied by increasingly ambitious attempts at regulation and stabilisation.

Nature reserve in Corsica © Sophie Heyd

The regulation of coastal conflicts often led to the creation of protected coastal zones and international agreements such as the Barcelona Convention against coastal and marine pollution. More often, however, state and private actors privileged infrastructural interventions and further colonisation of the coastal zone The stabilisation they sought to achieve, however, has remained elusive.

An Environmental History of the Anthropocene

The story of the coastal transition that we have begun to sketch out along the shores the western Mediterranean is therefore the story of an environmental stabilisation project – but one that is still disputed and unfinished. Moreover, even if the littoral at the end of the 20th century is undoubtedly more stable and developed than that of the early 19th century, the effects of climate change are radically destabilising this already precarious balance. The fascinating history of this stabilisation project, of its actors and conflicts, of its articulations, defeats and reconfigurations, remains to be written. It is a necessary history at a time when our littorals must be abandoned or thoroughly reconfigured once again.

Cyprus © Dimitri Svetsikas Pixabay License

This coastal history also raises questions about the period that many scientists have been calling the Anthropocene for the past two decades. This new geological era would be characterised by human influence on the Earth’s major processes, such as climate or coastal geomorphology. Examined from an environmental history perspective, it is clear that coastal change is by no means the result of a simply “human” influence, but rather of the intentions and actions of specific actors. Moreover, the persistent instability of littorals shows that having an impact does not imply having control. These lessons can contribute to avoiding the traps of anthropocentrism and of undifferentiated human responsibility, without eschewing an important and necessary interdisciplinary debate.

Translated by Carolyn Avery

As a researcher at Sciences Po’s Centre for History, Giacomo Parrinello studies and teaches the environmental history of industrial urban societies in the 19th and 20th centuries. He is interested in the interactions between natural systems and social processes, the techniques and knowledge that shape them, and the policies that emerge at the crossroads of environmental and social change.

Learn more

PARRINELLO, Giacomo, Renaud BECOT, Marco CALIGARI, and Ismael YRIGOY – “Shifting Shores of the Anthropocene: The Settlement and (Unstable) Stabilisation of the North-Western Mediterranean Littoral Over the 19th and 20th Centuries”, Environment and History , 2019.

Notes

| ↑1 | Christopher Small and Robert J. Nicholls, ‘A Global Analysis of Human Settlement in Coastal Zones’, Journal of Coastal Research, 2003. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The investigation continues today with the project “Shifting Shores: An Environmental History of Morphological Change in Mediterranean River Deltas over the 20th century” funded by the City of Paris with an“Emergences” research grant. |