While the end of slavery has been the subject of much research, its history is so diverse and complex that many of its dimensions remain understudied. M’hamed Oualdi‘s new project contributes to this body of research by seeking to uncover the transnational dimensions of this history in North Africa through an examination of the writings of slaves for this region from mid-18th century to the 1930s. The European Research Council selected this very innovative project in a highly competitive process. Interview.

With this project, you are trying to build a new narrative of the abolition of slavery in the Maghreb by adopting a transnational perspective. How did this idea emerge?

This project stems from previous research and teaching I conducted at Princeton on slavery in the Muslim world. More surprisingly, it also stems from a recent episode in the history of the Middle East that struck me.

This project stems from previous research and teaching I conducted at Princeton on slavery in the Muslim world. More surprisingly, it also stems from a recent episode in the history of the Middle East that struck me.

First of all, in previous research – presented in my book Slaves and Masters, The Mamluks of the Beys of Tunis from the 17th century to the 1880s (Editions de la Sorbonne, available online, in French) – I studied a particular group of slaves and servants: the Mamluks who served the governors of the Ottoman province of Tunis, occupying senior administrative and military positions. Hailing from the northern shores of the Mediterranean (Italy, Greece) and the Caucasus, the Mamluks are fascinating because they recorded their feelings, lives, and experience as servants in Arabic writings that they most often dictated to their Arabic-speaking secretaries, or even wrote themselves.

During a subsequent reading seminar on slavery in the Muslim world that I led at Princeton, I became familiar with a major field of study in the United States: slave narratives, which depict the lives and suffering of slaves of African descent, often with an abolitionist goal. One of these narratives from the West African Umar Ibn Said struck me because he defined himself as Maghrebi. This story led me to broaden my conception of the Maghreb to a wider geographical area.

Nadia Murad Basee Taha, telling her story during the Security Council meeting, Dec. 2015 © UN Photo/Amanda Voisard

Finally, a more recent event convinced me of the need to draw on the testimonies of slaves: listening to the testimony that Nadia Murad, a Yazidi woman enslaved by members of the Islamic State in Iraq, gave at a conference. She has since been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

You cover a period ranging from the mid-18th century to the interwar era. This is a much longer period than is generally associated with the abolition of slavery. Why did you choose this timeframe?

Many of us – and certainly the readers of this article – think in terms of abolitions and of particular moments regarding abolitions and black slaves in European history: the 1848 constitution in France, the Civil War in the United States, etc. But like other historians, rather than studying these issues at the short moments of abolition, I prefer to think over a longer run of the ends of slavery. These were gradual and sometimes very slow, if not uncertain. One need only think of West Africans who are still violently exploited during their migration to Europe today to realise that the last page of this history has not been turned.

I especially focus on the Maghreb and the Mediterranean, which were at the crossroads of at least four types of trafficking: the slave trades of West and East Africa (especially Ethiopia); the captivity of European slaves in the Maghreb; that of Maghrebi slaves (Muslims and Jews) mostly in southern Europe; and finally the much less known trafficking of Caucasians and Greeks in the Ottoman Empire, and especially in the Maghreb provinces of that empire.

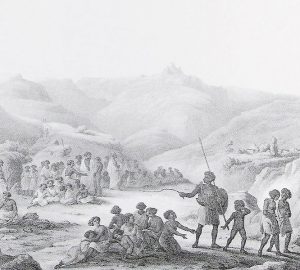

Slaves in Ethiopia – 19th century © Unknown / Public domain

Each of these forms of trafficking ebbed at different times. Thus, beginning in the last decades of the 18th century and up to the first two decades of the 19th century, diplomatic agreements concluded between Maghrebi and European countries enabled a reduction in the number of European and Maghrebi captives on each side of the Mediterranean, while the slave trade of Caucasian and West African slaves did not subside until the interwar period, and even then only very gradually. In short, there was a succession of ends to slavery worth studying together over what I would call a very long 19th century, especially because we need to understand why the enslavement of West and East Africans was so persistent, be it in this region or elsewhere in the world.

This leads you to qualify the role of the European colonisation of the Maghreb in both the establishment and abolition of slavery

I would not phrase things that way. First, in a context of rivalries, wars, and races between European and Maghrebi powers, men, women, and children were enslaved on both sides of the Mediterranean. Modern-era historians have shown that slave traders were not limited to the Maghreb. Malta, Rome, Cadiz, Venice and many other cities in southern Europe were terrible places of Muslim slave exploitation until the end of the 18th century. In addition, during both the modern period and the colonissation of the Maghreb, Europeans adopted different attitudes towards slavery: they either participated in the African slave trade or, in the case of British diplomats, they pushed for the abolition of slavery. There were also many French, Italian, and Spanish colonial officials in the Maghreb who considered that the fate of African slaves was not in their hands, but rather a private matter for the families and households employing these slaves in domestic service.

Sadok Bey meets Napoléon III in Algiers, 1861, by Alexandre Debelle ©, Institut national du patrimoine, collection Qsar es-Saïd

In fact, my priority is not to determine whether European powers were the only driving forces behind the abolition of slavery in the Maghreb, or whether there were also local movements pushing for abolition. This question has been explored at length in recent years to determine the rationales for, and limits to, the ends of slavery in the Muslim world. The goal of some historians was to show – legitimately – that the history of the end of slavery could not only revolve around Europe. Rather, this issue had to be considered in light of the specific social history of Muslim countries. For others, on the contrary, it was to demonstrate that Muslim countries were incapable of ending slavery on their own because enslavement and then slave ownership were Islamic precepts. The latter type of interpretation raises the risk of reductionism of the Muslim world, and the problematic insinuation that Muslim powers cannot modernise themselves.

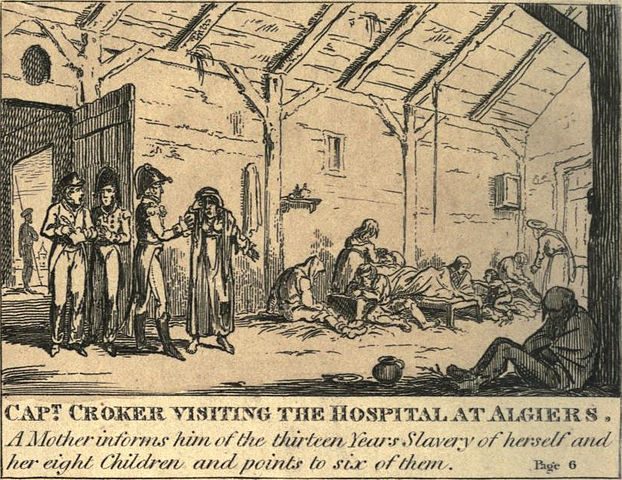

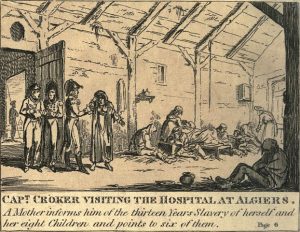

Captain Croker visiting the hospital at Algiers. A mother informs him of the thirteen Years Slavery of herself and her eight Children and points to six of them. juillet 1815 © Domaine public

In order to get out of this sometimes fraught and sometimes dead-end debate, and to think differently about the ends of slavery, in this project I followed the paths traced by historians of the Ottoman Middle East such as Eve Troutt-Powell and Ehud Toledano. I sought to understand the demise of the slave trade and of abolitions not only in terms of the actions of governments and diplomats, but predominantly in terms of the various experiences of slaves, starting with the documents pertaining to them: petitions written by slaves, testimonies collected during trials, and some rare life stories collected by European consuls and Maghrebi scholars …

An innovative aspect of this project is that you rely on written testimonies from captives. It is hard to imagine literate slaves taking up the pen, and it is also hard to believe that such documents have been preserved…

Yes, this is the major challenge, and one of the essential questions I find fascinating in this project: depending on the age, gender, and social and geographical origins of the slaves, as well as the types of administrative institutions in their countries of origin, slaves’ access to the written word was completely unequal. This is reflected in the first archives I was able to consult. For a first group of slaves – those who came from southern Europe and found themselves in captivity in the Maghreb, until the beginning of the 19th century, the European archives are overflowing with petitions and pleas for liberation addressed by the European captives to this or that Spanish, Italian, or French authority. At the same time – and this is the exciting work I have been involved in since this spring – slaves from the Maghreb (men, and more rarely, women) also managed to send their sovereigns and parents petitions written in Arabic. Only this type of writing is less widespread than the petitions from European captives, either because European powers censored the Maghrebi captives (we have extensive evidence of this), or because the Maghrebi powers did not attempt to, or had no interest in, keeping this type of petition.

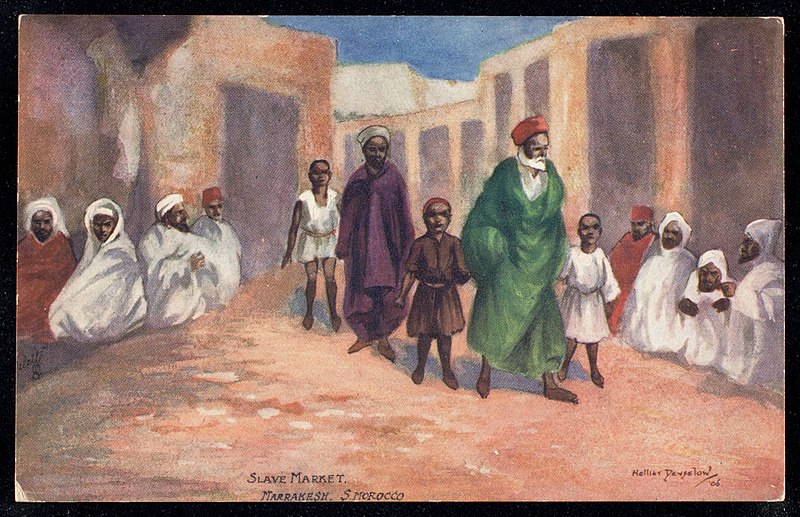

Slave Market. Marrakesh. S Morocco. Unknown author. Public Domain

While these archival imbalances will make it even more difficult to find the voices of West African male and especially female slaves, these voices have not been completely silenced. Traces of them remain in scattered form, especially beginning in the second half of the 19th century. For the latter group, we will have to be more creative in conducting our archival research. But these various asymmetries and archival inequalities once again say something fundamental about the diversity of the successive and unequally documented ends of slavery in the Maghreb and the Mediterranean.

Apart from the book that will result from this work, are you considering other media to share the results of this research? Can you mention them?

A central purpose of this research – to find and make the voices of the dominated heard – is to speak to different audiences. The publications resulting from this project will, of course, be academic pieces on the history of the Mediterranean, the Maghreb, slavery, and its abolition. But thanks to funding from the European Research Council and the support of the Center for History and other Sciences Po departments*, we also plan to produce a written anthology and perhaps audio or video recordings of slave testimonies that could be used by teachers in secondary and higher education. Looking forward, we hope that people in drama will channel the voices of slaves that we unearth and bring them to life onstage in various languages.

*I would especially like to thank Régine Serra, Marie-Laure Daggieu, Olivier Roméo, and Carole Jourdan for their daily and invaluable support.

Translated by Carolyn Avery

As a full professor at Sciences Po’s Center for History, and former associate professor at Princeton University, M'hamed Oualdi has focused his research on studying the modern and contemporary history of Maghreb areas that were under Ottoman domination. He is particularly interested in colonial domination issues and in the social and political trajectories of captives.

Esclaves et maîtres, Les Mamelouks des Beys de Tunis du xviie siècle aux années 1880, Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2015, available online

A Slave Between Empires: A Trans-Imperial History of North Africa, Columbia University Press, 2020