Influenced Choice: Why Opt for Lockdown?

16 March 2021

Passing Laws: When the End Justifies (or not) the Means

16 March 2021

Social service for children in moral danger, 1932. Source: private archives of1932. Source: SSE private archives Olga Spitzer

Lola Zappi is a recent history PhD graduate of Sciences Po whose thesis, which was awarded the Chancellery Prize and the Social Security History Committee Prize, focuses on the birth of social services (or social work) in the interwar period. Her research provides a highly instructive back-and-forth between an institutional and social history and individual narratives. Based on a body of files from the Service Social de l’Enfance, (SSE) a social service for children acting on behalf of the juvenile court, this work uncovers tensions between the impulse to help and the impulse to control, and between intentions and results. By analysing the institutionalisation of social services in the 1930s, this work exposes the ambitions and limitations of the developing social state. Interview.

Why did you pursue a research career after getting your Master’s in Public Affairs?

Lola Zaipi: Before enrolling in the Master’s program at School of Public Affairs, I had first considered pursuing a research master’s in history. But I wasn’t sure I wanted to pursue an academic career, especially since I knew that passing the agrégation and getting a PhD would be difficult! I ultimately opted for a hybrid solution: a Master’s degree in public affairs combined with a minor in history, replacing the internship with a research dissertation.

Louise Weiss, demonstration of “suffragettes”, May 1935 ©Public domain

This experience convinced me. In writing my dissertation on feminist activists at the beginning of the 20th century, I drew on a body of several hundred letters they had written to one another: it was very moving to access these letters that depicted times of struggle, but also of social encounters between women, daily life in Paris in the early 1900s, etc. I realised that history, even more so than sociology, enabled a detailed analysis of these life trajectories: without models or ideal-types, and with a real concern about not betraying sources and constantly paying attention to the context. I believe that the humility of this discipline, and the painstaking aspect of its work, contributed to my decision to pursue research.

You worked on social workers and assisted families in the interwar years. Why this subject?

Madeleine Delbrêl (1904-1964), social worker. © Friends of Madeleine Delbrêl, work on photos J.Faujour.

Lola Zappi: I wanted to combine my interest in public policy with a social history approach by asking myself how these policies affect individuals. More specifically, I wanted to understand how social services emerged in the interwar period and what the nature of the assistance relationship was between female social workers and those receiving assistance. I was able to explore this subject thanks to the discovery of an extraordinary trove of archives: the investigation and follow-up files of the Service Social de l’Enfance [Children’s Social Service], a private organisation of female social workers entrusted with taking care of families referred to the juvenile court of the Seine department (which included Paris and its suburbs at the time).

I was later able to study the student files schools of social work from the interwar years. The social worker profession first appeared then: I could see the first generations of women with this occupation. In my thesis, I sought to pair a history of the institution – what are social services? – and a history with social and human dimensions – that of the social workers and the people who were assisted..

What are the highlights of your thesis?

Lola Zappi: What I show is that social services institutionalized at a time of initiatives to rationalize social action while fighting “social scourges” such as tuberculosis, alcoholism, and endemic poverty. There was a strong impulse to control the lifestyle of working-class families exposed to these risks, and the care that social workers offered became a form of guardianship.

« Un aperçu de mes fils »: the Foyer de Soulins in Brunoy (1931) – Marie-Thérèse Vieillot: social worker (1920-1951)

This was also disconcerting to the young women who pursued the social worker profession: coming from the bourgeoisie and often imbued with Christian values, they primarily sought to become “friends” with working class families before realising that their profession also involved a certain amount of supervision and control. However, social services do not have an absolute power to control, and assisted people, including in the very specific field of judicial youth protection, managed to retain a certain level of freedom. In any case, the relationship between the social workers and the families they supported was distant.

What were the main objectives of these assistants?

Lola Zappi: The assistants from the Service Social de l’Enfance were in a way the precursors to probation officers (who appeared in France only in the 1950s). This translated into a particularly coercive approach: when they were entrusted with monitoring a child, whether the child was a delinquent or “in danger”, their first step was to place the child outside of his/her family home. These placements accounted for over half of all cases.

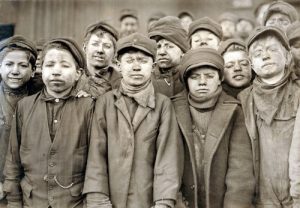

Child laborers portrayed by Lewis Hine in 1911. Crédits : Everett Collection, Shutterstock

Second, their actions mainly focused on the moral supervision of children (countering indiscipline, bad company, etc.), as well as professional guidance. In the interwar period, teenagers’ apprenticeship was crucial for both public authorities and private philanthropy. But this idea of investing in the professional training of young people often clashed with the will of the families followed by the Service Social de l’Enfance, since they were poor households looking to have their children work as soon as possible so that they could contribute to the family budget. Only a few families supported placements in vocational training institutes, either because they were better off or because the adolescent was placing too great a burden on the family..

Are there any other types of obstacles they had to overcome?

Lola Zappi: Yes, because they lacked the legal tools to enforce their decisions, particularly with regard to placements. What we see in the files is that the families would comply with the decision for the first few months, probably because the memory of the court continued to weigh as a symbolic threat. But I found that, on average, placements lasted only a year and a half; many parents ended up taking back their children despite the assistant’s disapproval.

Finally, families most resented the intrusion of social workers into family life. I observed many avoidance strategies (not being at home on the day of the visit, no longer showing any sign of life, and even being openly hostile) deployed to maintain some form of intimacy and independence.

You also underscore tensions between intentions and their effects…

Lola Zappi: That’s right. The interwar period saw the highly paradoxical birth of the social state: while reform-minded elites wanted to better integrate working class populations into society, their actions actually helped solidify a gulf between the institutions tasked with helping the working classes and the latter. This does not mean, however, that involved families refused social services altogether: they were keen on mobilising the financial, material, and even educational resources offered. I observed in particular how crucial social services were in 1930s Paris for families facing economic crisis and unemployment.

Albert Anker, The soup of the poor at Ins II, 1893 © Bern Museum of Fine Arts

You are now a history PhD. What are your plans?

Lola Zappi: As far as my research projects are concerned, I am beginning work on social services in rural areas in the 20th century. My thesis made me realise that the history of social protection remains highly focused on cities, and especially capital cities; we know nothing about the levels and forms of poverty in rural areas, and how it was addressed. I hope that this project will better convey the history of rural territories and bring to light those who were left behind by rural economic modernisation in the 20th century.

Interview by Violette Toye, PRESAGE

Lola Zappi is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the research center of the demography institute at Paris 1 University (Labex iPOPS), associate researcher at the Centre for history at Sciences Po (CHSP), and associate professor of history. Learn more.