![Palais du Luxembourg By Ibex73 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Salle_du_Sénat_2-80x80.jpg)

Lawmaking: a spurt of acceleration

10 April 2018

Understanding inequalities in higher education steering

11 April 2018University professor Marco Oberti is the head of the Center for Studies in Social Change. His research is often comparative and focuses on segregation in urban areas, especially in education. He has conducted many studies on the democratization of access to higher education. He uses both quantitative and qualitative approaches. Here he presents the findings of research based on a mapping of inequalities that relates socio-professional classes to academic results.

The variables often used to explain educational inequalities are the student’s gender and family type, the parents’ social origin and education, and – more rarely in the French case – the student’s migration origin. Inequalities in access and outcomes, guidance, skills and achievements, including  non-cognitive ones, are explained in relation to these factors, either considered in isolation or in interaction with one another.

non-cognitive ones, are explained in relation to these factors, either considered in isolation or in interaction with one another.

Spatial dimensions are rarely considered, even though they are key to understanding the dynamics unfolding in metropolises.

What are the relationships between urban segregation and school segregation? To what extent does their overlap affect the academic world and structure inequalities more broadly? How does the location of the institution attended by students influence their success and educational path?

When school segregation is greater than urban segregation

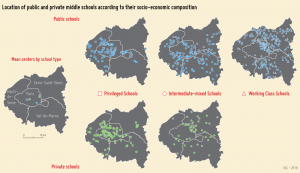

Location of public and private colleges according to their social profile. Source: OSC, Sciences Po. Click on picture to magnify

The mapping of academic results at the institutional level reveals that school segregation does not just reflect the urban segregation caused by districting. It is compounded by both the avoidance of this districting and the use of private options. At both ends of the social hierarchy, with upper class children on one end and working class children on the other, students are more segregated academically than residentially. For example, middle schools that should have a 30% share of students from working class families on the basis of their “district” actually had double that share! Similarly, while Paris’ three most working-class arrondissements (18th, 19th and 20th) are well represented in terms of being the residence of students admitted to Sciences Po from Paris, they disappear if one looks at the location of the high school; most admitted students come from high schools located in the capital’s central and western arrondissements.

Mapping and geographical variables enable a precise territorial grasp of these processes and resulting inequalities in terms of institutions’ social composition and in terms of success. They also help to assess the contiguity of spaces and to explain the difficulty of producing more social and academic diversity in the Parisian metropolis.

Socio-spatial hierarchies are reflected in school hierarchies. The mapping of types of middle schools by status – public or private, social composition and middle school exit exam results – shows how extreme the situation is.

The social and academic homogeneity of the central and western part of Paris and Hauts-de-Seine is clearly distinct from that of Seine-Saint-Denis.

The social and academic homogeneity of the central and western part of Paris and Hauts-de-Seine is clearly distinct from that of Seine-Saint-Denis.

The “rich neighborhoods” include institutions that are mostly home to students from the middle and upper classes, with a high concentration of private schools. Regarding middle school exit exam results, between 30 and 50% of students obtained the two highest distinctions (bien or très bien), compared to average shares that rarely surpass 13 %.

Finally, while chances of obtaining one of the two highest distinctions on the exit exam are the same for upper-class students regardless of whether the school is public or private, chances are respectively 2.2 and 2.5 times higher for working-class girls and boys when they attend a private school. Similarly, chances are 2.2 times higher if they attend a middle school with mostly privileged people versus a working-class middle school.

The advantage of being educated at a public Parisian middle school

A second spatial inequality exists: when only working class middle schools are considered, the chances of obtaining one of the two highest distinctions are significantly higher at middle schools located in Paris than in ones located in the suburbs. This effect is particularly strong for upper-middle-class students who attend predominantly working class middle schools in the Hauts-de-Seine, a suburb where areas and institutions with a high share of upper and upper-middle class students coexist with predominantly working-class ones. For these students, attending a working class school is often associated with downward mobility and strong stigmatization.

The socio-spatial dimensions of admissions at Sciences Po

The relevance of spatial dimensions is also reflected in analysis of admissions at Sciences Po. If one looks at a combination of factors – high school location, the student’s social environment and his/her academic performance – and differentiates between two admissions processes (the Convention Éducation Prioritaire – CEP – and exams), relatively distinct admissions results appear.

For the CEP, admissions in the Parisian region include more working class students with lower academic results; in other French regions, admissions include more privileged students of a higher academic level.

In the exam process for admissions to Sciences Po, the gap is widest between upper-class students from high schools in Paris or in privileged Western suburbs and students from other regions with a lower social status but better grades on the early exams of the baccalaureate; the latter do better.

This reflects differences in social structures, with the Parisian metropolis characterized by a much larger share of higher-income groups, particularly in the private sector. The result is a relatively less favorable position in a particularly selective academic environment, wherein the relative position of the middle class in the rich neighborhoods of the Parisian metropolis is less privileged that that of their counterparts residing in other regions.

Another hypothesis linked to the previous two is based on the idea of compensation for social rank, or even territorial position, through academic rank. Thus, the legitimacy of applying to Sciences Po for students from other regions is predicated on “academic excellence”, whereas this is less true for Parisian students, who are more likely to automatically apply to the institution despite average academic results. The lower “social legitimacy” of applying to Sciences Po for students from the regions is thus partly compensated by their stronger “academic legitimacy”: regardless of social origin, the share of students with grades above 16 (equivalent to an A) is systematically higher for students from regional high schools.

This might also reflect an effect from the high schools themselves, given that the most prestigious ones, which are mostly located in Paris and several privileged towns in the Western suburbs, precisely built their reputation on their ability to place students in selective programs. The proximity of some of the teachers of these “grands lycées” to the grandes écoles promotes dissemination of a norm of guiding students towards these prestigious programs. In some ways this trivializes a choice that in other contexts requires academic excellence. From this perspective, the situation of students from the diverse and working-class suburbs of Paris is closer to that of students coming from “ordinary” high schools in other French regions.

Previous article: Learning to read: encouraging family reading to reduce inequalities <-> Next article: Understanding inequalities in higher education steering