ELIPSS: Portrait of the French Under Lockdown

3 July 2020

How Voters Respond to Crime Control Policies

3 July 2020In his book Les maladies du bonheur [Happiness diseases] published last March, Hugues Lagrange, an emeritus CNRS research director at the Observatory of Social Change (OSC) has tried to reflect about modernity.

He has chosen to focus on the evolution of mental and behavioral diseases, which he considered to be emblematic of an individualised way of life – an essential mark of modernity. Written before the appearance of Covid-19, he has announced that “future illnesses could once again bear the mark of collective responsibility, and, as a result, encourage a return to activities that are more conducive to psychological balance, if not meaning”. Current events appear to have proven him right, at least in terms of collective responsibilities. Debates about the post-Covid world are only just beginning.

The Coronavirus Draws an Inverted Map

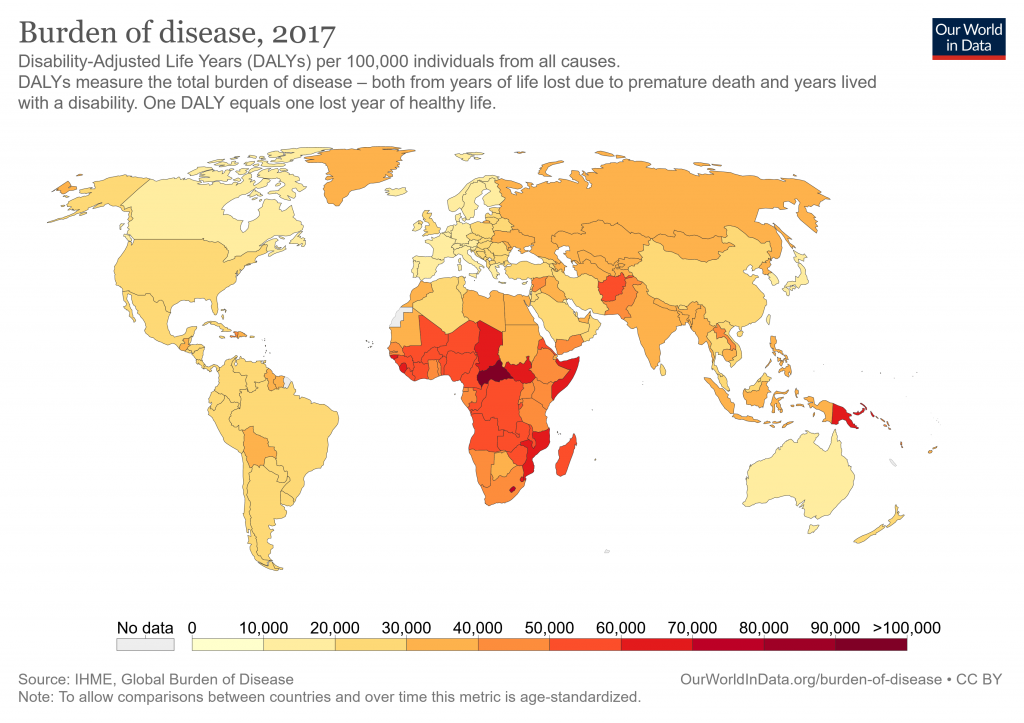

The dissemination and severity of the epidemic in Western countries is surprising in many ways. Fifty years ago, as antibiotic and vaccine use became widespread, it looked like the battle against mass infections had been won. The world of “Pasteurian” diseases seemed to be a thing of the past for Westerners: Ebola, Zika and Chikungunya were seen as exotic threats, but the current epidemic is reviving the collective terrors of the past – plague, cholera, typhus. Over the last thirty years, reports from the Global Burden of Disease, a World Health Organisation (WHO) research program that monitors global morbidity trends, have underscored a massive reduction in the load of communicable diseases in emerging countries, identical to that observed in Western countries at the beginning of the 20th century.

Thirty years ago, communicable diseases dominated the nosographic landscape in emerging countries(1)An infectious disease is a disease caused by a microorganism and thus transferable to new individuals. It may or may not be transmissible. A non-communicable infectious disease can be attributable to toxins from food or the environment, such as tetanus. The GBD program’s “communicable diseases” category includes infectious and parasitic diseases, particularly lower respiratory tract infections, diarrhea, AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria..

Thirty years ago, communicable diseases dominated the nosographic landscape in emerging countries(1)An infectious disease is a disease caused by a microorganism and thus transferable to new individuals. It may or may not be transmissible. A non-communicable infectious disease can be attributable to toxins from food or the environment, such as tetanus. The GBD program’s “communicable diseases” category includes infectious and parasitic diseases, particularly lower respiratory tract infections, diarrhea, AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria..

Since then, there has been a shift towards diseases – cancers, cardiovascular diseases, obesity, mental disorders, drug use – that reflect the individualisation of lifestyles. This trend, which is also unfolding in the poorest countries, remains very partial. And the life expectancy of the residents of these countries is still drastically lower than that of wealthy and emerging countries, in particular because of the persistence of infectious diseases. As a result, the map of the burden of disease on life expectancy shows the contours of poverty: life expectancy is short in countries where the burden of communicable diseases remains high, chief among which are sub-Saharan African countries.

The current pandemic does not follow this pattern. While the number of deaths attributed to the coronavirus is around 400,000 worldwide, the pandemic is mainly affecting the population of wealthy countries with close economic ties to China; it has relatively spared sub-Saharan Africa, eastern Indonesia, and poor areas of the Caribbean. It is noteworthy that around April 10, the Dominican Republic – a country of 10 million people with a per capita GDP of $7,650 – recorded 265 deaths, while Haiti – a country of a similar size but among the world’s poorest, with $854 per capita – reported only 5 deaths. A strange reversal has thus occurred: the coronavirus pandemic is now drawing an almost inverted map, where the most and least developed countries have switched places.

Individualisation of the Severity of Contamination

Epidemics usually strike indiscriminately, providing a shared fate. This is not the case with the coronavirus, which has proven to be a disease that affects each individual differently. This individualisation has manifested itself during this epidemic in several ways that Hugues Lagrange analyses in his book.

DNA © Tartila, Shutterstock

The first way relates to the role of our biogenetic identity. The severity of coronavirus-related diseases is based on the genealogical dimension of our individuality, as suggested by Jean-Laurent Casanova of the Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases (Imagine Institute, Paris). “The [current] hypothesis is that these patients have a genetic predisposition that remains silent until the first encounter with the virus, and then manifests itself in the form of a serious disease, leading the patient to an intensive care unit. According to this hypothesis, it is upon encountering the infectious agent that the phenotype manifests itself, that is, that your genotype – the vulnerability of your genes to this infectious agent – is revealed. […] Several teams have already discovered genetic variations that confer selective susceptibility to certain infectious diseases, depending on the age of encounter with the infectious agent… making each person’s reaction unique”.

The virus thus reminds us that the resistance of each one of us depends on an inheritance from the gene pool that links us to our ancestors. The danger is not only, and perhaps not primarily, external, since the host’s genes determine the vulnerability to coronaviruses. The seriousness of the risk linked to these predispositions is not only fatality, but the manifestation of the fact that, from the inside, we are aggravating the destruction wrought by an external agent.

Another aspect of this virus’ action pertains to the individualisation of ways of living. “Sometimes hosts may overreact to the presence of the virus. This is the case, for example, with hepatitis B, where the liver disease is linked to immune hyper-reactivity; this is also the hypothesis of researchers working on the coronavirus. The most serious cases may be linked to a runaway immune system in the host via inflammatory mediators called cytokines”(2)This description comes from Eric Caumes and Mathurin Maillet from the infectious disease department of Pitié-Salpêtrière, Le Monde 17 April 2020 . In these patients, the immune system – as is the case with autoimmune diseases – attacks the body it is supposed to defend. Here again, individual qualities play a major role; the virus is surprisingly reflexive.

Animated map (click on the image) of the United States showing the prevalence of obesity 1985-2010. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In addition to this genetically and immunologically differentiated susceptibility, the severity of the damage and the probability of death associated with the coronavirus reveal the burden of the long-term diseases that are emblematic of modernity. It has euphemistically been written that the severity of the ailments attributable to the coronavirus is particularly high among individuals with comorbidities. Yet these diseases – cancer, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and the deterioration of lung tissue – are precisely, and more so than infectious diseases, the expression of our lifestyles and our choices. While the elderly are more seriously affected (30 times higher lethality for people over 70 than for those under 40), the variability of the impact on them highly depends on maintaining physical activity and avoiding excessive alcohol and sugar.

Hugues Lagrange highlights the processes by which the current epidemic is modern: its seriousness may well be more variable among individuals than among social classes, because it is the differential fragilities accumulated over the course of life that create inequalities vis-à-vis the coronavirus. If poverty in rich countries is associated with the case-fatality rate of the virus, it is because poverty is generally synonymous with poorer health. This is not the case at the global level, where poverty is correlated with a triangular age pyramid(3)The pyramid has a very wide base (high birth rate) and a very thin top (high mortality). In France, the age profile is more bell-shaped (wide for the 40/60 year olds). A country with an ageing population has a fairly small base and a broad top..

In this sense, in affluent societies, the SARS-Cov2 pandemic presents a range of pathological variations that reflect the importance of our genetic legacy, our personal immune history, and above all the consequences of the individualisation of our behavior. It echoes the individualisation of ways of living.

The Disappearance of Security and Solace

August 5, 1969: Beginning of the Woodstock festival © Flickr / Paille

The author recalls that in the 1950s and 1970s, as the world opened up and authoritarianism receded in the West, there was a constant denunciation of the social control and disciplinary role of states. On both sides of the Atlantic, there was talk of repressive de-sublimation(4)According to Freud, civilisation can only rise by repressing the instincts that would make social life impossible. The repression of the pleasure principle causes the instincts to sublimate themselves.. In the United States, psychiatrists and psychoanalysts considered the growing caseloads of anxiety and depression to be associated with tensions between emerging desires and restrictions imposed by society on lifestyle freedoms. Interpreting Freud in a hemiplegic way, the psychological malaise was given the same diagnosis as that of the Viennese women of 1890 and the women of Victorian society in England and the United States.

The study of 20th-century Western diseases developed by Hugues Lagrange shows, on the contrary, that social straightjackets are not behind the discomfort. He explains that people indiscriminately stripped themselves of a second skin consisting of primary communities – extended families, local solidarity, and communities of faith. At the same time as religious ties dissolved, they experienced urban anonymity, the disappearance of extended families, and a rise in divorces: the combination of these developments had negative consequences for many. The disappearance of the interlocking securities that these ties formed was particularly harmful for the working classes.

Pietà de Nouans. Painted by Jean Fouquet, around 1460-1465 © Public domain

The author also shows that with the Reformation and the establishment of consistories, a consoling god was replaced by a guilt god. And the guilty man from the Reformation, weakened by the disappearance of micro-social protective envelopes, experiences a more individualised anxiety. The anxio-depressive syndrome has indeed been more prevalent in northern Europe and the United States than in southern and eastern Europe (at least until recently). Ordinary mental diseases in Europe in the second half of the 20th century overlay with advances in freedom and the de-institution of ways of living. This suffering is geographically more acute where freedom from personal dependencies is achieved.

An Illusory Emancipation?

Correlating modern suffering with the hubris of freedom is obviously schematic. Developed by Kierkegaard – with the image of the man on the edge of the cliff, suffering from the dizziness of freedom – it also suggests that modern man can only regain psychological balance by making freedom a requirement. Indeed, while suffering, especially in the dominated classes, is associated with freedom in ways of living, the suffering does not derive from the freedom.

© Shutterstock

The movement towards freedom erred when it gave up on the quest for autonomy in all areas and become about nothing more than eliminating moral constraints – a pure emancipation from dependencies. And for many freedom has been defeated because freedom acquired in the private sphere has not been accompanied by an expansion of autonomy in the work world.

Refuting the idea that emancipation from interpersonal dependencies assigned at birth has made man truly free, Hugues Lagrange stresses, in an analysis of meritocracy, the extent to which inherited native inequalities have not disappeared. The elimination of statutory distinctions attached to birth has brought to light inequalities in the distribution of abilities that are no less strong. We are, he says, probably not the authors of our successes and failures any more so than in past, but rather only modest co-authors of our lives. To be real, the expansion of legal freedoms needed to be accompanied by freedom from debt, and this was rarely accomplished.

Freedom and Bio-Power

Questioning the excesses of freedom, Hugues Lagrange disagrees with the idea that a form of bio-politics has developed in Western countries over the past few decades. The very invocation of surveillance societies in European countries, where substantive measures were put in place to combat terrorism, is misguided. True, surveillance – perpetual commercial tracking and its use by Western states – has developed to the point of excess, but to label them as bio-political is a complete misinterpretation. In the 1980s, Michel Foucault envisioned an evolution towards a continuously growing state hold.

Manifestation à Clermont-ferrand © Loz Pycock, CC BY-SA 2.0

But the state, even where it is most firmly established in Europe, has been continuously delegitimised. As we moved away from a state that intervened directly in our lives(5)Although the share of public spending in GDP continues to grow, its pace shows the hesitation over the state’s role that appeared in the 1980s. The rise in public spending came to a halt under the influence of anti-redistributive ideas in the United Kingdom, the United States and Ireland (which, incidentally, saw spending resume its growth from 1990 to 2000), while the most typical social democratic states – Sweden and Norway – saw the share of this spending stagnate from 1990 onwards, and its growth slowed significantly in Germany. Only France saw its public spending grow steadily from 1930 to 2010. and as guaranteed moral freedoms continued to expand, the perception of a disciplinary state, making its mark through bodies, nevertheless flourished over the last thirty years. For examples of bio-politics, we need to look elsewhere, and especially during this epidemic, in China. The Chinese state has interfered in the most intimate areas of life, notably with the single child in 1979, the control of suicides in the 1990s, and the massive use of geo-location and facial recognition. During the SARS-Cov2 pandemic, following the example of several Asian countries, with the exception of China, northwestern European countries distanced themselves from purely coercive practices imposed physically. They instead relied on other resources. Meanwhile, Italy, with its very strict closure of the northern regions; Spain, with the intervention of the army; and France, with police control of travel permits – have exercised a mix of coercion and oversight. Even in the latter cases, however, surveillance did not taken the Orwellian and totalitarian form it did in China or Iran.

Thus, Hugues Lagrange’s analysis of the happiness diseases opens multiple avenues to thoroughly question our societies’ relationship to health, to the evolution in our ways of living, to our beliefs, to the effects of our “responsible” solitude, and to our attachment to “good freedoms”.

Translated by Carolyn Avery

Hugues Lagrange, Emeritus CNRS Senior researcher at the Observatoire sociologique du changement (OSC), is interested in socialisation and identity relationships.

Notes

| ↑1 | An infectious disease is a disease caused by a microorganism and thus transferable to new individuals. It may or may not be transmissible. A non-communicable infectious disease can be attributable to toxins from food or the environment, such as tetanus. The GBD program’s “communicable diseases” category includes infectious and parasitic diseases, particularly lower respiratory tract infections, diarrhea, AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | This description comes from Eric Caumes and Mathurin Maillet from the infectious disease department of Pitié-Salpêtrière, Le Monde 17 April 2020 |

| ↑3 | The pyramid has a very wide base (high birth rate) and a very thin top (high mortality). In France, the age profile is more bell-shaped (wide for the 40/60 year olds). A country with an ageing population has a fairly small base and a broad top. |

| ↑4 | According to Freud, civilisation can only rise by repressing the instincts that would make social life impossible. The repression of the pleasure principle causes the instincts to sublimate themselves. |

| ↑5 | Although the share of public spending in GDP continues to grow, its pace shows the hesitation over the state’s role that appeared in the 1980s. The rise in public spending came to a halt under the influence of anti-redistributive ideas in the United Kingdom, the United States and Ireland (which, incidentally, saw spending resume its growth from 1990 to 2000), while the most typical social democratic states – Sweden and Norway – saw the share of this spending stagnate from 1990 onwards, and its growth slowed significantly in Germany. Only France saw its public spending grow steadily from 1930 to 2010. |