Armed Conflict: the Growing Impact of International Law

16 April 2023

Counterterrorism: How to Fail Most Successfully

16 April 2023By Chiara Ruffa

As conflicts change and evolve, there is one fundamental tool of multilateralism that does not wane: United Nations (UN) peacekeeping. Symbolised by the iconic image of Blue Helmets deployed in every corner of the planet, the United Nations deploy peace missions to keep and build peace, enforce temporary governance, conduct limited combat operations for the sake of security, and prevent the outbreak of conflict. With 92 different countries deploying almost 70,000 military troops to 12 missions worldwide as of 2020, UN peacekeeping is a complex and massive endeavour with important implications for world peace and global security. Studying peacekeeping is not only important per se: studying this microcosm allows us to capture key features of contemporary international politics, such as the nature of their hierarchies and their diversity.

UN Peacekeeping: A Success Story

Since its inception, the UN has deployed 72 missions of which 12 are still ongoing today. A wealth of studies using a plurality of sources and models are adamant: set aside notable and devastating failures, like the genocide in Rwanda or Srebrenica, peacekeeping works and protect civilians from violence. For instance, estimates suggest that over a 13-year period, UN peacekeeping operations were able to save 150,000 lives in comparison to a scenario without a peacekeeping mission(1)Hegre, Havard ; Lisa Hultman & Håvard Mokleiv Nygård, 2019 – Evaluating the conflict-reducing effect of UN peacekeeping operations, in The Journal of Politics..

But, perhaps surprisingly, we know a lot less about how peacekeeping actually works to achieve those aims. Researchers have highlighted the importance of the deterrent effect of having peacekeepers deployed, others think that it is rather persuasion, signalling or commitment of the Blue Helmets on the ground(2)Howard, Lise. 2019. Power in Peacekeeping. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press.. There seems to be a growing recognition that mandates alone – often rather vague and recycled from mission to mission – do not directly determine what actually happens in the field. We know that mandate interpretations differ across peacekeepers as a function of pre-existing military cultures, training templates, and routines(3)Bove, Vincenzo, Chiara Ruffa, and Andrea Ruggeri. 2020. Composing Peace. Mission Composition in UN Peacekeeping. Oxford: Oxford University Press.. We still know little, however, about how – once deployed – such interpretations emerge and how Blue Helmets translate an ambiguous mandate into action. To fill this lack of information and analysis, I study peacekeeping on the ground as a complex and multifaceted endeavour(4)Ruffa, Chiara. 2018. Military Cultures in Peace and Stability Operations. Afghanistan and Lebanon. University of Pennsylvania Press..

Some Interesting Facts About Peacekeeping

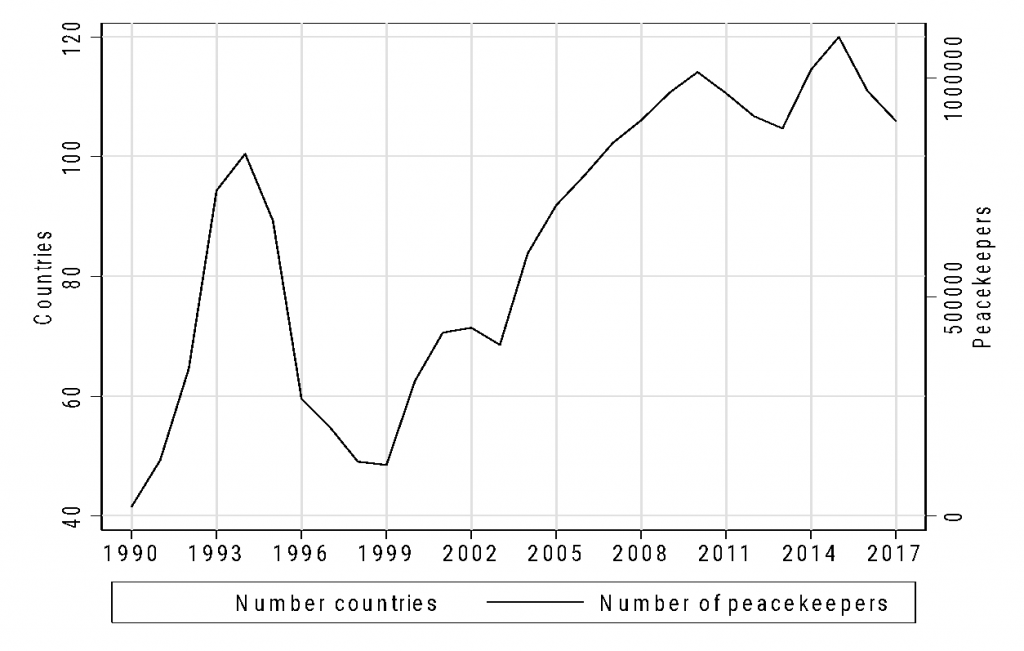

Peacekeeping today is a quintessential multilateralist endeavour. Over the past 30 years: peacekeeping missions have become larger and more complex(5)Bove, Vincenzo, Chiara Ruffa, and Andrea Ruggeri. 2020. Composing Peace. Mission Composition in UN Peacekeeping. Oxford University Press..As we can see in this graph, UN peacekeeping personnel increased a lot both in terms of numbers of peacekeepers deployed and in the number of countries supplying peacekeepers. We went from 46 countries contributing peacekeepers in 1990 to 124 in 2018. Along similar lines, the UN went from 11,000 peacekeepers deployed globally in 1989 to over 100,000 peacekeepers in 2018.

Graph 1 – Numbers of countries which mobilised peacekeepers (1990–2017)

Vincenzo Bove, Chiara Ruffa and Andrea Ruggeri, 2020, Composing Peace: mission composition in UN peacekeeping, Oxford University Press, p. 5.

This has meant that most missions are now larger: missions like the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) deploys 18,000 personnel. The increased level of ambition has made missions not only larger but also structurally more complex, with diversified and specialised command structures and compositions, and increasing need for specialised skills with specialised units and tasks.

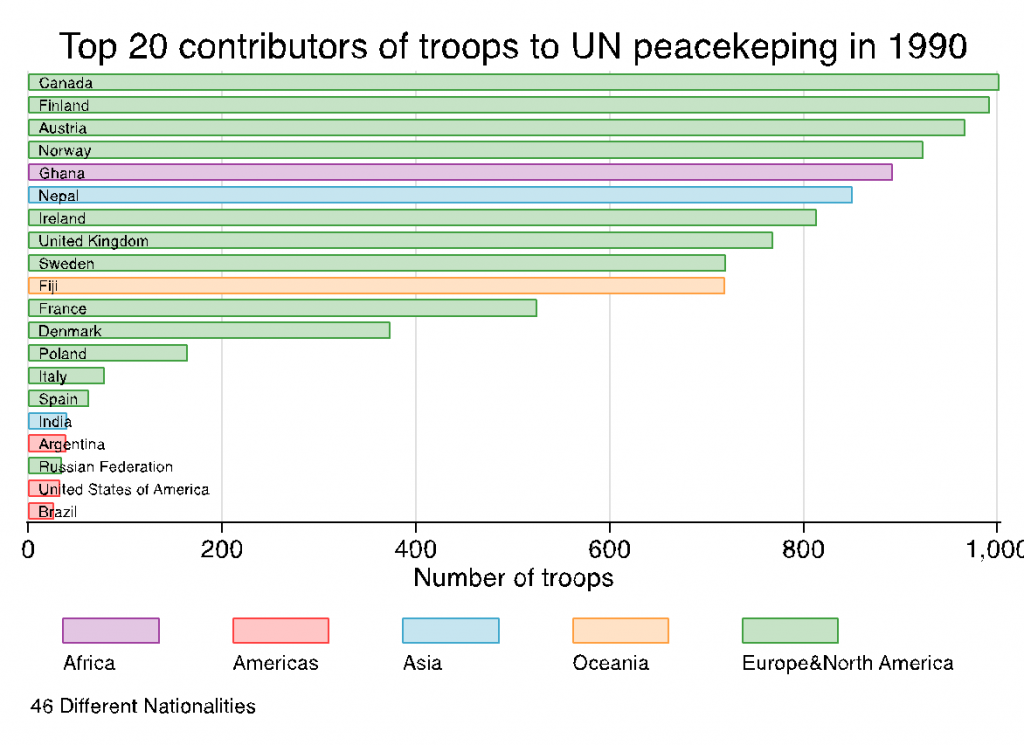

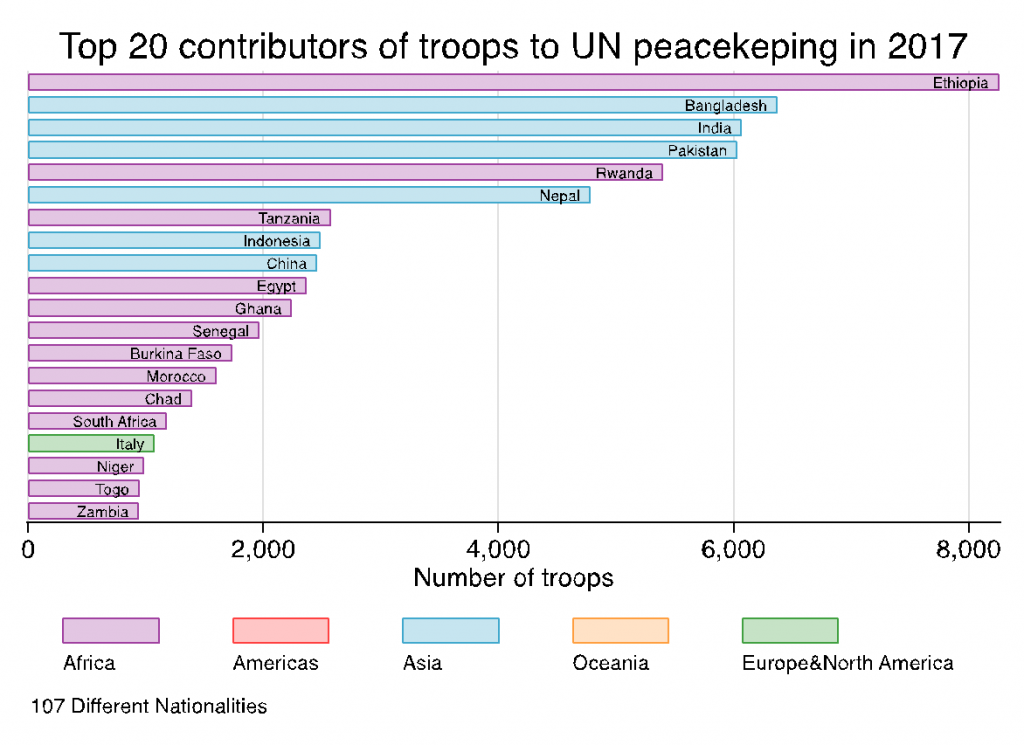

The second fact about peacekeeping is perhaps even more revolutionary: the composition has changed completely and missions have become very diverse. Graphs 2 and 3 show that while in 1990 the top Blue Helmet contributors were from the Global North(6)We use the categories of Global North and Global South. This last being short-hand of the regions of Latin America, Asia, Africa and Oceania. If these categories are questionable, they allow us to capture the production and reproduction of hierarchies in UN peacekeeping. (in green), as of today we have a predominance of Blue Helmets from Asia and Africa. Importantly, Blue Helmets from the Global North have not disappeared but are deployed in specialised functions, for instance collecting intelligence and usually performing functions that do not require the Blue Helmets to be much outside the base. Each mission displays a lot of cultural diversity. To illustrate, as of today, the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) deploys peacekeepers from 64 countries. To sum up, peace missions have become larger, more complex and multilateral. In Composing Peace: mission composition in UN peacekeeping, we show that the increased diversity per se – as shown by these trends – is actually a decisive determinant for peace outcomes. We find that overall diversity of mission composition is a powerful tool for peacekeeping effectiveness across dimensions of mission composition.

Graph 2 – Top 20 contributors of troops to UN peacekeeping in 1990

Vincenzo Bove, Chiara Ruffa and Andrea Ruggeri, 2020, Composing Peace: mission composition in UN peacekeeping, Oxford University Press, p. 8.

Graph 3. Top 20 contributors to UN peacekeeping in 1990

Vincenzo Bove, Chiara Ruffa and Andrea Ruggeri, 2020, Composing Peace: mission composition in UN peacekeeping, Oxford University Press, p. 10

However, these different cultures coming together to each single mission and having to work together towards the same mandate can occasionally also create friction.

Studying multilateralism on the ground: from New York to Bamako

To study these dynamics, we need to examine peacekeeping on the ground. Within the field of International Relations, researchers tend to study multilateralism at a high level, for instance in the corridors of the United Nations Headquarters in New York. But what happens if we shift our focus from New York to, for instance, Bamako, where one of the biggest and most ambitious peacekeeping missions is deployed? In several of my articles and books, I have explored how multilateralism runs through the various layers of multilateral institutions and organisations, all the way to the ground where agents from diverse backgrounds take action to implement decisions. In a recent article, my co-author Bas Rietjens and I study precisely that, how this multilateralist endeavour plays out on the ground. We focus on one of the most ambitious ongoing peacekeeping missions, the UN Integrated Multidimensional Stabilisation Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) which currently is deploying Blue Helmets from 56 troop-contributing nations. We specifically explore processes of meaning-making by peacekeepers in this mission to document the process through which soldiers from the Global South and Global North translate an ambiguous mandate into action(7)Ruffa, Chiara, and Sebastiaan Rietjens. July 2022. “Meaning Making in Peacekeeping Missions: Mandate Interpretation and Multinational Collaboration in the UN Mission in Mali.” in European Journal of International Relations.. We focus on one dimension of peacekeeping practices that has become increasingly important, namely, how peacekeepers relate to other peacekeeping contingents with whom they are supposed to implement their mandate, thus being in need of interaction. Unveiling meaning-making helps us understand how to enhance coordination and collaboration among contingents serving together in multinational contexts and how to dismantle racialised hierarchies.

Meaning Making in UN Peacekeeping: Three Strategies

Meaning-making is a very common human activity, which we all practise and which has received a lot of attention in other disciplines beyond International Relations. In this paper, we borrow the concept of meaning-making from the sociological literature, in which it is often used to refer to the human and common process through which individuals give meaning to their surrounding context. Meaning-making is common because ‘humans constantly seek to understand the world around them, and that the imposition of meaning on the world is a goal in itself, a spur to action, and a site of contestation(8)Kurzman, Charles, 2008, “Meaning-making in social movements”, in Anthropological Quarterly..

Makilimbo, Haut Uele, DR Congo: Peacekeepers helping the civilian population in their daily activities in Makilimbo. Photo MONUSCO/Force

Meaning-making is particularly likely to occur when the surrounding context is ambiguous, in other words, when it is open to more than one interpretation. While meaning-making constantly happens, it becomes particularly crucial in times of stress and ambiguity. We systematically documented how deployed peacekeepers display three different meaning-making strategies: Voltaire’s garden (Candide, ou l’Optimisme, 1759), building bridges, and othering. We label the first strategy ‘Voltaire’s garden’, following Candide’s habit to tend his own garden. Here, soldiers try to focus on narrowly defined terms of the mission. Voltaire garden type of interpretation entails that soldiers respond to ambiguity by explicitly and strictly focusing on their day-to-day tasks and activities and ignoring perceived absurd or strange things that may be happening. We find that Voltaire’s garden is associated with behaviour that does not improve other troops’ efforts and is ultimately diminishing the ability to fulfil the mandate. While Voltaire’s garden is about how (narrowly) a unit interprets the mandate, othering and building bridges are about how a unit understands and interacts with other ones. We label the second strategy of building bridges: ambiguity is dealt with by activating several informal connections with other troops or units. Building bridges may lead to a more creative interpretation of the mandate, thereby helping soldiers to adopt a problem-solving approach. The third strategy is othering, or the distancing of a group – the high-tech Western troops in this case – from the rest of the mission, hence making it less likely to overcome inconsistencies. ‘Othering’ ultimately reinforces identity differences, thereby diminishing peacekeepers’ ability to implement the mandate. As such, othering and building bridges lie on two extreme ends of the spectrum of the us/them divide, Voltaire’s garden by contrast relates to the extent to which the peacekeepers abide by the mandate: strictly or not. Each of those strategies leads to distinct modes of cooperation, with implications for the mandate implementation.

But how did we capture those dynamics? My coauthor and I embarked on extensive fieldwork in the UN multidimensional mission in Mali. We adopted a pragmatic, exploratory, approach that started from the empirical observation on the ground. Our study necessitated a focus on how the peacekeepers understood and made sense of their mandate, how they talked and reflected about it and its interpretation. To be able to study meaning making, we embraced an interpretive sensibility. We acknowledge that ‘the “view from nowhere” is an illusion […] We rather get to “reality”, or make sense of it((Kurowska et Bliesemann de Guevara, 2020 – Interpretive Approaches in Political Science and International Relation, SAGE Publishing.).

Much like interpretivists, we emphasise the impossibility to completely distinguish the object of our study from who studies it. The nature of the evidence and the accidental way in which it was collected obliged us to be pragmatic, humble, and aware of the limits of our approach. We have let ‘the meaning of the concepts themselves “emerge” in situ as the researcher learns what is meaningful to situated members, rather than being defined as a priori and brought to the field to be tested’. Our approach has been iterative – based on a back and forth between the field and the concepts under construction – as well as accidental and we have let the field speak to us.

Meaning Making Matters

25 April 2015. Bukavu, South Kivu – DR Congo: Egyptian peacekeepers during a ceremony organized in their honor prior to leaving the Mission. Photo MONUSCO/Abel Kavanagh

These trends manifest themselves on the ground and multilateralism on the ground is crucial for macro-outcomes. How the mandate is implemented and which meaning making strategies also prevail matter for peace because it helps us understand how these mandates are carried out and how civilians are protected. For instance, ‘othering’ lead to severe coordination failure between some troops, some of the contingents taking eventually a decision to withdraw their contribution or to move to other sectors and no longer protect civilians from attack. When we adopt this micro sociological approach, we are able to capture things that we could not see before. We observe a neocolonial pathology that is concerning through these racialised hierarchies but also via cooperation and building bridges. Peacekeepers create and co-create the meaning of the policy itself through formal and informal dynamics, which means how multilateralism works and even what it is constantly created and recreated. Our work suggests that some specific creative solutions, such as “building bridges” may increase effectiveness, even though it may entail violating the mission structure. “Othering ” should be discouraged at all organisational levels. We need to minimise” Voltaire’s garden’, train peacekeepers to be flexible, and facilitate ‘building bridges, induce structural changes to dismantle racialised hierarchies and build trust, for instance, by having cultural diversity in each area of responsibility, through pre-deployment training and socialisation. It is a key priority to work on cross-cutting cleavages to undermine racialised hierarchies, whereby we do not associate specialised tasks with Global North Blue Helmets and foot patrol with Global South Blue Helmets. Better understanding multilateralism on the ground could improve the ability of peacekeepers to implement their mandate, keep peace and protect civilians. In other words, one of the main challenges of UN peacekeeping should also be one of its main strengths.

Chiara Ruffa is a Professor of Political Science, specialising in International Relations, at the Centre for International Studies (CERI). Her research is about multilateralism on the ground, peacekeeping operations, norms, cultures and civil-military relations. In particular, her research agenda revolves around multilateral governance and management of peace and security across different regions.

Notes

| ↑1 | Hegre, Havard ; Lisa Hultman & Håvard Mokleiv Nygård, 2019 – Evaluating the conflict-reducing effect of UN peacekeeping operations, in The Journal of Politics. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Howard, Lise. 2019. Power in Peacekeeping. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press. |

| ↑3 | Bove, Vincenzo, Chiara Ruffa, and Andrea Ruggeri. 2020. Composing Peace. Mission Composition in UN Peacekeeping. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

| ↑4 | Ruffa, Chiara. 2018. Military Cultures in Peace and Stability Operations. Afghanistan and Lebanon. University of Pennsylvania Press. |

| ↑5 | Bove, Vincenzo, Chiara Ruffa, and Andrea Ruggeri. 2020. Composing Peace. Mission Composition in UN Peacekeeping. Oxford University Press. |

| ↑6 | We use the categories of Global North and Global South. This last being short-hand of the regions of Latin America, Asia, Africa and Oceania. If these categories are questionable, they allow us to capture the production and reproduction of hierarchies in UN peacekeeping. |

| ↑7 | Ruffa, Chiara, and Sebastiaan Rietjens. July 2022. “Meaning Making in Peacekeeping Missions: Mandate Interpretation and Multinational Collaboration in the UN Mission in Mali.” in European Journal of International Relations. |

| ↑8 | Kurzman, Charles, 2008, “Meaning-making in social movements”, in Anthropological Quarterly. |