Migrations: On-Going Research Projects

16 November 2020

Is There Such a Thing as “Anti-White Racism”?

16 November 2020

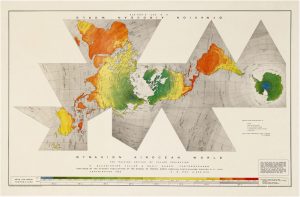

The dymaxion world view of R. Buckminster Fuller, 1954

Researchers in migration politics predominantly examine immigration and integration policies in Western democracies. Just like any other field in social sciences, this empirical ethnocentrism mirrors the geography of scientific institutions, the economics of research funding and the politics of academic publications.

Apart from raising ethical issues, these limitations constrain our understanding of international migration politics, firstly, by neglecting empirical realities that are relevant – notably migration politics in the Global South – and secondly, by creating methodological biases. Documenting less-researched cases offers an obvious remedy to the problem. Yet the future of research on migration politics is not only about more research on “non-Western others”. It is about using single-case studies and comparative research across types of states and political contexts to weed out some of the most blinding assumptions of migration theories and to open up new research avenues.

This could first be achieved by considering seemingly “most different” political contexts across countries and comparing, for instance, democratic apples and authoritarian pears. It could also be achieved by paying more attention to migration histories and tracing political processes and institutions across time with greater care. By doing so, we would go beyond merely including more Southern case studies but rather expanding, amending or recasting migration theories based on the new knowledge generated by this approach.

Gaps and Biases in Migration Politics Research Today

Understanding migration requires looking across the various units of analysis that are traditionally distributed across academic disciplines – states, individuals, families, ethnic groups, cities, labour markets, firms, networks, l’individu, la famille, le groupe ethnique, la ville, le marché du travail, l’entreprise, les réseaux – and taking into account multiple levels of enquiry, from the most intimate to the global. As more experienced social scientists have written, this is the main challenge for migration studies in the next decade.

Anthropological research and its critique of biases induced by methodological nationalism have infused a “transnational awareness” into migration studies. Yet, the citizen- migrant dichotomy still shapes academic discussions on contemporary polities, rights, memberships and identities. Additionally, states are still often studied as operators of migration politics and not the other way around, as if migration could not affect the state. The most-cited scholarship on migration politics looks at power configurations and influences within the state: state-business relations or state- courts relations, civil society activism or political cultures of incorporation.

When scholars bravely step across the borders of Western-centric social sciences for single-case or comparative studies , they often use Western analytical frameworks to describe the inputs, drivers, substance and effects of migration policies in the Global South. Unlike anthropologists, geographers and sociologists, political scientists rarely take cities, neighbourhoods, groups (including diasporas), regional groupings, inter-governmental or transnational institutions as units of analysis for migration politics.

To sum things up, research on migration politics 1) still generally focuses on immigration or asylum in Western case studies; 2) when dealing with non-Western context, it mostly focuses on emigration and diaspora politics to Western contexts or on mass asylum 3) considers that states are still the main unit of analysis.

A UNHCR worker prepares repatriation kits which are distributed to returnees of Internally Displaced Persons, East Timor, November 1999. Crédits : United Nations Photo. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

In democratic settings, for instance, the key factors for migration politics are considered to be institutional or political-party bargaining, business or civil society lobbying, the impact of courts or the media, and the role played by expert knowledge. Conversely, undemocratic contexts, the key factors for migration politics are considered to be informality, criminal networks, family/ patrimonial/kinship dynamics, structural economic determinants (poverty, development level), and, last but not least, international interventions (whether development, humanitarian, security/peace- related).

New Research Venues

Single and multiple-case comparisons in migration politics across time and space will not only help fill these gaps but also change our assumptions, expand existing research methods and widen the scope of migration theories:

- Emigration politics from the Global North/ developed countries (“expatriate studies”) which are often depoliticised and analysed through a merely economic lens;

- Immigration and integration politics in the Global South;

- Asylum politics and refugee integration in the Global South.

To expand the validity of migration theories, scholars have used Western- grounded frameworks in non-Western contexts. Several authors, for instance, have expanded theoretical discussions on the making of migration policy and empirical examples from the Global South of “migration states” which James Hollifield defined as states where migration discourses and management is central.

Rajasthan government has set up a panel to ensure ease of travel for stranded labourers. 96,000 migrant labourers have been taken to their home states May 2020 © Awaz Multimedia

Audie Klotz has contributed to international relations theories of norm diffusion by looking at migration politics in South Africa ; Katharina Natter has tested the effect of political systems on migration policy making in Morocco and Tunisia; Fiona Adamson and Gerasimos Tsourapas have offered new typologies of states built from examples from the Global South. Political scientists have also paid attention to the privatisation of migration management in Europe, both through its legal and illegal actors and institutions. Political anthropologist Biao Xiang has explicitly charted an innovative theory of state/non-state relations in Asian migration politics. Similarly, by grounding their insights in Asian cases, Brenda Yeoh and Gracia Liu-Farrer have sought to bring about original theories in migration studies on the politics of space, mobility and immobility along gender, ethnicity and class identities. We can also remember that Myron Weiner’s much-cited work on migration politics and security stemmed from in-depth knowledge of the political demography of India.

Building upon these experiences, comparing migration politics in immigration countries like the United States, Singapore, Russia, Canada, Saudi Arabia, Côte d’Ivoire, Qatar, or Germany could shatter our assumptions about migration policies, their drivers and effectiveness and the strength or weakness of states across regimes and times.

Migration Politics as State Making

Migration is commonly seen as a challenge to sovereignty , a threat to national identity or state security , or even as a life- biological threat as the restrictions on mobility in times of pandemics have shown. Emigration is also conceptualised as a threat to regimes and nation-states, a domain where the authority of states seeks to be extended often at the expense of non-state actors. This is what historians tell us when they narrate the invention of passports and explain how states have tried to control human mobility. This is what studies of diaspora politics illustrate as well. But apart from a few exceptions, theorists have rarely taken the critical stance seriously enough: what if “mobility makes states” rather than immobility? This argument, made by Darshan Vigneswaran and Joel Quirk based on a collection of African cases, should be expanded. By determining international relations between states, delineating the contours of the nation, shaping state capacity and authority over “their ” population at home and abroad, and organising state-societies relations, migration politics can be seen as a promising way to understand state making.

Thinking about migration politics as a determinant of state-making processes across time answers Abdelmalek Sayad’s invitation to rethink, denaturalise and rehistoricise the state.

Réunion d’information pour les migrants du centre d’hébergement du Secours Catholique « Cité Bethleem », Déc. 2016. Crédits : Alain Bachellier

Firstly, immigration makes states, through politics and processes of formal and informal incorporation or exclusion. Such a perspective obviously moves away from the idea of incorporation into pre-existing social “containers” according to predefined political norms regarding diversity (ethnic, multicultural, republican, etc.). On the contrary it is an invitation to conceptualise integration as a process of co-production of the Nation rather than assimilation. It calls for combining governmental and everyday politics in order to understand the production of otherness (integration, exclusion) as co-producing nations. Alongside formal integration policies and labour market dynamics, the everyday politics of spatial segregation and access and political and social interactions and practices offer a bottom-up, practice-based and spatialised viewpoint on migration politics as nation-builder. These are the sites where the processes of boundary making, polity building and institutionalisation of politics can be observed. Ethnographers have shown, for instance, how refugee politics are determined between official policies and asylum laws, humanitarian interventions and the everyday interactions that impact access to material and immaterial resources in migrant camps, jungles and informal urban encampments.

By way of transnational extension, the building of the nation and the state also happens “from afar” via diaspora politics. In Eritrea, in the Philippines, in Turkey, in Senegal, in India, in China, in Algeria, as well as in France or Italy, emigration politics enforce political control over nationals abroad, extract remittances, and organise or prevent political participation through external voting.

©TonelloPhotography, Shutterstock

Moreover, emigration and transnational dynamics also change states and change our assumptions on the territorial dimension of state building. Beyond the well- known case of Israel, various state-building processes (Palestine, Eritrea, Sri Lanka, Kurdistan) need to be approached through the diasporic lens. Diasporas make states; diasporas can also make, or change, political regimes. Such insights feed into scientific debates on democratization and transnational politics: can emigrants from non-democratic countries settled in democracies change the regimes of their state of origin? More generally, the relationship between emigration, immigration and revolution started to be discussed during the Arab Springs and within debates around transnational activism and external voting. Taking migration into account would certainly enrich and deepen existing theories of revolution.

Finally, “migration as state building” is obviously relevant to conceptualise and investigate state building in settlers’ states and colonial and post-colonial contexts like the United States , Australia Canada but it is also fruitful to understand state transformations across history in the United Kingdom , France, Germany, Latin America, the Gulf monarchies etc. Scholars of migration politics would benefit from building even more upon the work of global historians who have brought migration and citizenship into a comparative analysis of state building processes both in former colonies and in imperial metropolises.

Seeing migration politics as a structuring feature of state-building processes amounts to investigating what migration does to the nature of the state, its practices and policies, to political regimes and state-society relations, therefore reversing the usual perspective on “migration control.” In this perspective, I have argued that mass immigration to the oil-producing Gulf monarchies is more than a consequence of labour market demands and that immigration policies are not mechanically “determined” by oil rentierism. Rather than incidental, migration policies and politics are constitutive of a regional social order and modern state-building processes happening both in immigration and emigration states).

References

- Adamson, F. B., & Tsourapas, G. (2019). The Migration State in the Global South: Nationalizing, Developmental, and Neoliberal Models of Migration Management. International Migration Review.

- Sayad, A. (1999). Immigration et “pensée d’État”. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, 129(1), 5–14.

- Thiollet, H. (forthcoming). Illiberal Migration Governance in the Arab Gulf. In J. Hollifield & N.Foley (Eds.), Understanding Global Migration. Stanford University Press.

- Vigneswaran, D., & Quirk, J. (Eds.). (2015). Mobility makes states: Migration and power in Africa, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Hélène Thiollet, CNRS researcher at the Center for Internanational Studies examines migration policies in developing countries. She is particularly interested in the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa. See her publications