The EU’s planned reconstruction efforts of Ukraine: A game changer?

13 November 2023Organised crime encompasses a broad range of activities and people, from peasants in Colombia to transnational corporate actors. Due to the diversity of actors, a global analysis of organised crime does not allow us to understand its different workings. Moreover, some activities are still poorly documented. In order to fill these gaps, Federico Varese, a professor of sociology at the Centre for European Studies and Comparative Politics and specialist of mafias, proposes a new framework that distinguishes three key activities of organised crime groups: production, trade and governance.

Based on extensive data collection, he wants to find out whether or not those functions overlap and shed light on how groups specialised in one function differ from those with other specialisations. This is the ambition of the CRIMGOV project (2021–2026) for which he has received support from the European Research Council highly selective Advanced Grants programme. Interview.

Mafias have been the main focus of your research. What have you learned about the conditions for their emergence and survival? Are there common features?

Federico Varese: I have been studying mafias since I was a PhD student in Oxford. At the time, I was interested in the end of the Soviet Union. My first published paper(1)Is Sicily the future of Russia? Private protection and the rise of the Russian Mafia, European Journal of Sociology, 1994 , in 1994, was a comparison between the emergence of the Sicilian mafia and the Russian mafia.

Federico Varese: I have been studying mafias since I was a PhD student in Oxford. At the time, I was interested in the end of the Soviet Union. My first published paper(1)Is Sicily the future of Russia? Private protection and the rise of the Russian Mafia, European Journal of Sociology, 1994 , in 1994, was a comparison between the emergence of the Sicilian mafia and the Russian mafia.

It drew on the work of my supervisor, Diego Gambetta, who had shown that the mafia in Sicily emerged as a consequence of a flawed transition to a market economy, which happened quite late compared to other parts of Europe. In the early 1800s, feudalism ends in Sicily, land and water access are privatised, there is a market which needs to be regulated, a middle class emerges. But the state is unable to define and protect property rights. And at the same time, there is a supply of people trained in the use of violence, who used to work for feudal lords, and now start to provide protection, not just to one particular lord but to the members of the middle class.

I wanted to check whether that idea also applied to the case of the Russian mafia, in the context of the end of the Soviet Union. It was also a case in which the state was not equipped or able to define and protect the new property owners. And at the same time, in Russia, too, there were people trained in the use of violence who became suddenly unemployed, coming either from the Afghan war, or they were coming out of prison as a consequence of the transition to democracy.

Other cases like that of Japan are very similar. In the 19th century, Japan went through wars between feudal lords, which exhausted them, and the power ended up to be centralised in the figure of the emperor. The people who used to work for the feudal lords became unemployed and started to offer their protection to the new property owners, because the Japanese state took a long time to meet legal protection needs. That’s how the Yakuzas emerged. So you start to see a framework that explains the emergence of mafias. And they survive, ultimately, because the state continues to be unable to convince people to use its services when they need, for example, to settle disputes. In Sicily, for instance, the legal settlement of disputes is extremely inefficient: it can take 12 to 20 years for a case to be settled in court. So the mafia can settle all kinds of disputes in the legal markets (such as disputes over access to premises, payment of rents, the delivery of construction works, as well as retrieving stolen goods), and of course, it also continues to operate in the illegal markets, where drugs are the main commodity.

In my book Mafia Life (Oxford University Press, 2018), I took a step further, trying to highlight more similarities between mafias: the Japanese Yakuzas, the Hong Kong Triads, the Russian mafia, the Sicilian mafia, the Italian-American mafia. A lot of the scholarship on mafias was about the differences between these organisations; and of course, there are cultural and historical differences. But my contribution is to show that there are also key similarities that we need to highlight, and not only in the way they emerge: all the mafias that I studied are organised in a similar way, they penetrate similar markets, they’ve got similar rules of behaviour for their members, they’ve got rituals.

In your current project, you go beyond mafias and study different types of organised crime, from cybercrime production hubs, to the international trade of drugs from Colombia to Europe, gangs in London, and the emergence of criminal governance in prisons in the former Soviet Union. What is the aim of this comparison?

F.V. :I am very grateful for this European Research Council grant (an Advanced ERC) which allows me to take a risk into exploring something new. The CRIMGOV project really takes this step forward, way beyond traditional mafias, and it makes a key contribution by considering that the illegal markets – in which mafias operate, but not only mafias – are divided in three key functions.

Within illegal markets, you have people who are involved in the production of goods and services. The quintessential example is the peasants working in coca fields in Colombia, harvesting coca leaves that are eventually processed into cocaine. They are employees of a firm, as agricultural workers (just as are the chemists transforming coca leaves). They are very much localised, and they don’t make that much money.

So it would be a huge mistake to confuse these people with big drug traffickers who have the job of transporting cocaine powder across the world. The professional profiles and skills are very different.

Coca cultivation. Credits: Alain Labrousse

The third building block of this framework is that, next to those who produce, next to those who trade, there are those who govern a place – be it a local market, or a community, a small neighbourhood. And those are, in a sense, the traditional mafias, but not only. There are other forms of criminal governance, ranging from some urban gangs (which often start out controlling local drug distribution) to insurgent groups (that control and govern territories, like the FARC in Colombia used to). And of course, governance can also occur within prisons, and that’s a very big topic in Latin American, studied for example by our colleague Gabriel Feltran, and a contribution of my work in Russia.

So the point of this framework is to help us clarify the different types of activities that go on in the underworld, which we can broadly call organised crime, or just illegal markets.

You often say that this framework allows you to study the state without studying the state. What do you mean?

I think studying mafias can highlight the raw behaviour of states. Mafias have to govern territories, they have to settle disputes, enforce property rights of commodities – that happen to be most of the time illegal, or illegally obtained.

A reputation for being effective and strong is very important to build up their ability to govern and that also stands for states: states use their reputation to deter attacks from others (this is how nuclear deterrence works). Mafias and the state tend to be monopolies of power: they want to be the only one in a territory to govern – now, they do not always succeed because mafias exist within states. Also, mafias protect some businesses and reduce competition for those businesses they protect, and this also applies to states that apply protectionist measures.

So if I were to write a textbook in sociology, I would not put organised crime and mafias under the part of crime and deviance, I would put them in the chapter on the state because for me they belong to the same theoretical ‘box’, they are closely related concepts.

In people’s minds, mafias and organised crime are part of a mysterious underworld. What tools do you use in this project to study those ‘hidden’ activities and organisations?

When you study the mafia, you have to triangulate and use all the sources you can: qualitative data, quantitative data, archival material. Ethnography, based on field interviews and observations (not participant observation with the mafia, but observations of life in the places we go to) is an invaluable tool. For this project, the team that I brought together stayed in Colombia for three months and will do some more fieldwork there. We were planning to do field work in Russia but because of the war, we are going to Georgia instead. We did repeated trips to London and Nottingham. Of course you have to keep yourself safe: we are not undercover, we make sure we’re not hiding anything or pretending to be someone different from who we are. I always said to the people I was interviewing: ‘never tell me anything that is a secret that only you and I know, I want to know what everybody knows.’

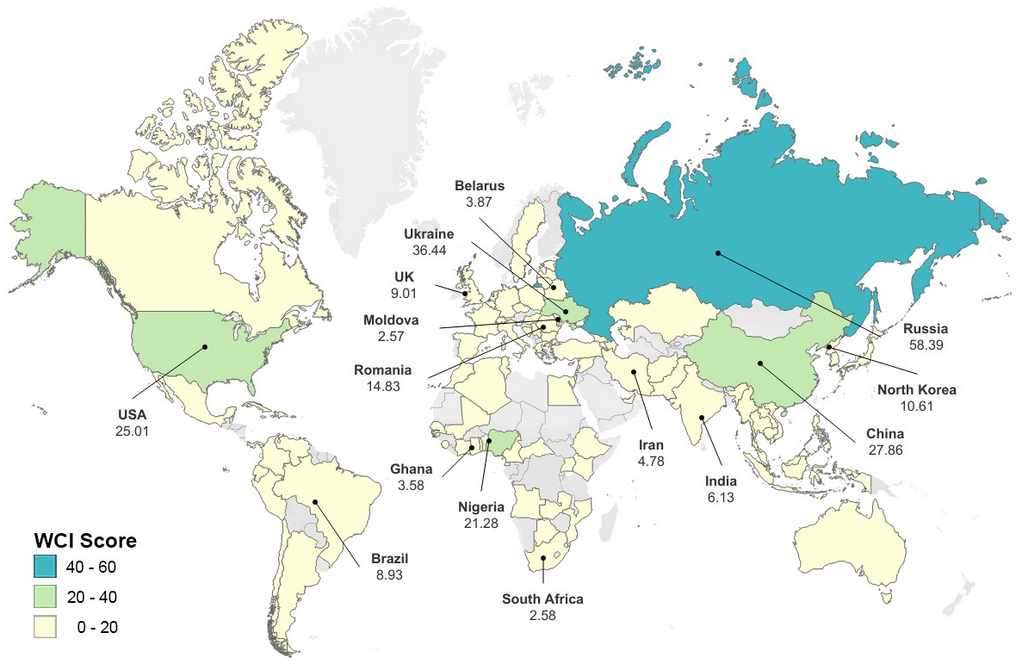

We also interview journalists, prosecutors and community activists in other parts of the world (in Italy, for example). And we created a worldwide index of cybercrime — Mapping the global geography of cybercrime with the World Cybercrime Index — , that was based on a survey among experts, in order to locate the main production hubs of cybercrime, based on the type of attacks. We just published a paper that had good media coverage and the data set can now be used by other people.

Once you have collected the data, you can analyse them in different ways. Something I spent a lot of time doing is social network analysis (i.e. the analysis of structures made of social actors). This is a very suitable technique for studying criminal organisations, because the groups we study are rather small (20, 50 maybe 100 people but that’s already huge), with people that are not independent from each other. Social network analysis allows you to see who is in touch with whom. Taking one step further, we can test some hypotheses using sophisticated data techniques developed by statisticians: for example, what amount of reciprocity do we find? What is the effect of gender or social status?

Mapping the global geography of cybercrime, World Cybercrime Index

by Miranda Bruce, Jonathan Lusthaus, Federico Varese

Europol recently published a report about the EU’s most threatening criminal networks. How does your research project contribute to the knowledge used in policy making?

I think that those kinds of reports, as valuable as they are, still fail to distinguish that criminal networks or criminal organisations do different things.

If you want to fight, say, the fact that a poor guy, in order to survive and to feed his family, is working as a peasant in a field which happens to produce coca leaves, the kind of strategy you have to follow is very different from arresting a burglar.

And if you want to fight the mafia, of course, you have to arrest the mafiosi who murder and kill. But the essence of the mafia is that they govern territories in alternative to the state. So you also need to make the state more efficient at dispensing justice or protecting the citizens, for instance.

Those are the key policy implications: you have to tailor your intervention to what people actually do and not, as often is the case in policing in this field, at how these people are organised as a hierarchical structure or a flat network. This is our policy, as well as intellectual, contributions.

Interview by Véronique Etienne, academic outreach officer at the CEE

Federico Varese is professor of sociology at Sciences Po and researcher at the Center for European Studies and Comparative Politics (CEE). His research interests include organized crime, corruption, Soviet criminal history, social network analysis, and analytical social theory. He is the author of four monographs — The Russian Mafia. Private Protection in a New Market Economy (2001), Mafias on the Move: How Organized Crime Conquers New Territories (2011), Mafia Life.Love, Death and Money at the Heart of Organised Crime (2018) and Russia in Four Criminals (Polity , 2024), and an edited collection, Organized Crime (2010). Previously, he was Professor of Criminology (2004-2023) and Head of the Department of Sociology (2021-2023) at the University of Oxford. He has testified before parliamentary committees in Canada, Italy and the United Kingdom. He was selected by the American Society of Criminology as the 2024 Recipient of the Thorsten Sellin, Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck Prize.

Notes

| ↑1 | Is Sicily the future of Russia? Private protection and the rise of the Russian Mafia, European Journal of Sociology, 1994 |

|---|