The secrets of the Hermitage

6 July 2019

Are Domestics Back?

10 July 2019 Who remembers that worker unions used to be organized at the international level, much earlier than the corporate and financial worlds? In his book La Lutte et l’Entraide. L’âge des solidarités ouvrières , Seuil, 2019 [The struggle and mutual aid. The age of worker solidarities], the historian Nicolas Delalande revisits the “internationals”. These transnational worker movements were inescapable for close to a century, before experiencing a slow decline at the turn of the 1970s.

Who remembers that worker unions used to be organized at the international level, much earlier than the corporate and financial worlds? In his book La Lutte et l’Entraide. L’âge des solidarités ouvrières , Seuil, 2019 [The struggle and mutual aid. The age of worker solidarities], the historian Nicolas Delalande revisits the “internationals”. These transnational worker movements were inescapable for close to a century, before experiencing a slow decline at the turn of the 1970s.

This book is a history of worker internationals: what about this topic interested you?

Nicolas Delalande: In current debates about Europe and globalization, open and borderless elites are often set in opposition to the immobile and protectionist working classes. This vision obscures a major historical fact: for close to a century – from the 1860s to the 1970s – worker movements were at the cutting edge of internationalism.

The creation in London of the International Association of Workers in 1864 was a turning point. What would later be called the “First International” aspired to bring together European and American workers across languages, nationalities, and trades. It was a major undertaking in a context marked by opening borders, moving capital, and exploding inequalities. The objective of my book was simple: to understand how international worker solidarity developed, what it accomplished in the 19th and 20th centuries, and why it collapsed over the past forty years, to the point of disappearing from our memories.

You focus on practices and not just ideologies. What is interesting about the exploration of practices?

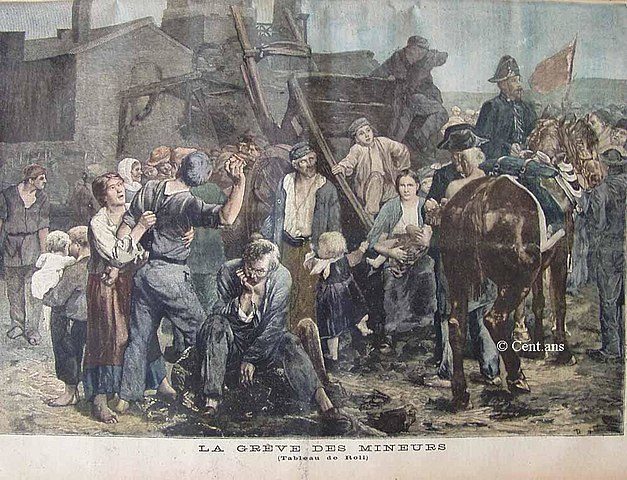

![Illustration of the 1892 miner's strike at the Compagnie minière de Carmaux, by Alfred Philippe Roll [Public domain] Illustration of the 1892 miner's strike at the Compagnie minière de Carmaux, by Alfred Philippe Roll [Public domain]](https://www.sciencespo.fr/research/cogito/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/627px-La_Greve_des_Mineurs_Le_Petit_Journal_1_Octobre_1892.jpg)

Illustration of the 1892 miner’s strike at the Compagnie minière de Carmaux, by Alfred Philippe Roll [Public domain]

The question of competition between local and immigrant workers was raised early. How did internationals address this question?

N. D.: We sometimes forget that the second half of the 19th century saw the birth of mass migration at the continental and transoceanic level. Societies at the time were far from still. Tens of millions of Europeans left their region or country of origin to go look for work elsewhere. For internationalist activists, this mobility marked both an opportunity and a risk. Free movement is a fundamental right that workers proudly asserted.

Climbing into the Promised Land, Ellis Island. 1908. Source : Library of Congress. Public Domain

It was becoming increasingly easy for capital and goods to circulate, so why wouldn’t this be the case for workers? But questions were already being raised at the time about the potentially negative effects of this opening if employers used foreign labor to break strikes and depress salaries. Herein lied the internationalist struggle: how to reconcile the free movement of workers and the collective improvement of their work conditions?

A first option consists of establishing unions in many countries to coordinate strikes and demands. This accounts for the big wave of mobilizations in the 1890s-1900s, with a watchword shared by the whole workers movement: the 8-hour workday. But in the 1880s-1890s, protectionist trends started to emerge. Some unions, especially in the United States, called for closing borders (vis-à-vis Asian migrants), in the name of the defense of existing workers on the national territory, even if the latter were also of immigrant descent….

Securing and harmonizing social rights at the supranational level does not appear to have been an important objective of the internationals. Why?

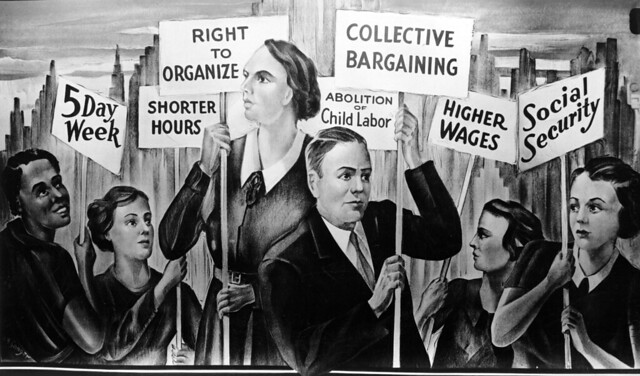

Mural of workers holding placards. Kheel Center. Collection: International Ladies Garment Workers Union Photographs (1885-1985). CC BY 2.0

ND.: At the time of the First International (1864-1876), workers aspired to emancipate from any form of tutelage, be it capitalist or statist. They wanted to build horizontal solidarity based on reciprocity and interdependence. It is through struggle and mutual aid that they sought to defend their rights and challenge authoritarian powers. The anti-state dimension of their mobilization was clear.

This strategy evolved during the Second International (1889-1914). Worker parties increasingly seized on universal suffrage and called for the adoption of social legislation (labor law, retirement, progressive taxation). It is not until after 1919, with the creation of the International Labor Organization, that reformers started promoting social justice internationally. In response, the Soviet Union sought to universalize its revolutionary project during the Third International (1919-1943), which was must more centralized and bureaucratic than the previous two.

You say that the weakening of “local” intermediary bodies, and especially unions, played an important role in the decline of worker internationalism. Isn’t this contradictory?

N. D.: Worker internationalism has deeply ebbed since the 1970s. Unions’ decline and their waning political influence partly explains the return of a situation that Marx and the founders of the First International had decried: one featuring a profound imbalance between the free movement of capital and the atomization of work worlds. Yet international consciousness is always rooted in local experiences. Mobilizations for climate justice and tax justice continue to show this today: it is through small solidarities that great causes are born.

Nicolas Delalande is a professor at Sciences Po’s History Center. His recent research focuses on the history of the State, inequalities, and solidarity in 19th- and 20th-century Europe. He previously worked on the history of consent and resistance to taxation (Tax battles. Consent and resistance from 1789 to today, 2014) and coordinates an international research project on the global political history of political debt since the end of the 18th century (Emergence of the City of Paris program).

Nicolas Delalande, La Lutte et l’Entraide. L’âge des solidarités ouvrières, Seuil, avril 2019 All the publications of Nicolas Delalande