Pesticides. How to Ignore What We Know

3 July 2020

Cogito 11

3 July 2020

HE Uhuru Kenyatta, President, Republic of Kenya © Chatham HouseCC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Better understanding the state of political systems – particularly in developing countries – via methods used by economists does not appear to be commonplace. However, it is an increasingly popular approach that provides results complementing those obtained by political scientists. Benjamin Marx, a researcher in the Department of Economics, has demonstrated their relevance in research he has conducted in sub-Saharan Africa and Indonesia.

You study political economy questions in developing countries with an economist’s approach. Why this choice? What does economics bring to the analysis of phenomena that are usually the focus of political scientists?

Benjamin Marx – I am convinced that an interdisciplinary approach brings immense value to the study of political phenomena. Several of my projects are collaborations between economists and political scientists: this is the case of a n experiment I conducted on vote buying in Uganda(1)Eat Widely, Vote Wisely? Lessons from a Campaign Against Vote Buying in Uganda Benjamin Marx, Chris Blattman, Horacio Larreguy and Otis Reid, NBER Working Paper, September 2019., and of a study exploring the relationship between the 1960 land reform and Islamic institutions in Indonesia(2)The Institutional Foundations of Religious Politics: Evidence from Indonesia, Benjamin Marx, Samuel Bazzi and Gabriel Koehler-Derrick, Quarterly Journal of Economics, May 2020.. Both projects were collaborations involving researchers across the two disciplines.

Election day in Uganda – 18 February 2016 © The Commonwealth, CC BY-NC 2.0

In this interdisciplinary approach, political science brings its conceptual tools, its deep knowledge of institutional mechanisms (indispensable for understanding electoral phenomena), and its precise understanding of local contexts. In my work on Africa I have especially drawn on the work of political scientists such as Joel Barkan and Jeffrey Herbst, who have influenced many scholars in both disciplines.

Meanwhile, economics and econometrics bring their methodological tools as well as great rigor to causal inference, which refers to a researcher’s ability to establish a causal relationship between two variables X and Y. This type of approach has recently allowed economists to improve our understanding of political phenomena in developing countries.

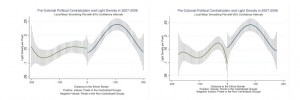

Precolonial Politcal Centralisation and Light Density, © Stelios Michalopoulos and Elias Papaioannou

For example, two Greek economists – Stelios Michalopoulos and Elias Papaioannou(3)Stelios Michalopoulos and Elias Papaioannou, Pre-colonial Ethnic Institutions and Contemporary African Development, Econometrica, January 2013. – have established the existence of a long-term relationship between pre-colonial political institutions and the different levels of economic development observed in sub-Saharan Africa. Other economist-led research has improved our understanding of phenomena at the crossroads of economics and other social sciences, such as corruption.

There is now a fairly broad consensus among development economists around the importance of institutions in the emergence of longstanding trends in economic development. My thesis supervisor, Daron Acemoglu, has significantly contributed to this research. To study the political economy of developing countries is to attempt to understand the political and institutional mechanisms that hinder the eradication of poverty, the improvement of health and education conditions, good governance, etc. It also sparks imagination about potential solutions.

H.N. – You recently studied voter turnout in Kenya. How did you proceed and what conclusions did you reach?

Kenya Election Posters

© Heinrich Böll Stiftung CC BY-SA 2.0

B.M. – This was a project conducted in collaboration with the Electoral Commission of Kenya in 2013, aiming to promote citizen participation in a difficult institutional context. The previous presidential election in 2007 had led to an outburst of interethnic violence in the country, leading Kenya to reform its electoral process and to adopt a new Constitution.

The experiment focused on the evaluation of simple messages transmitted to citizens by SMS, providing basic but essential information on the revamped electoral process. For example, some messages contained simple reminders about the practicalities of the voting process, while others sought to explain in simple words the role of various political functions.

Using a randomised evaluation, we were able to show that these messages increased voter turnout– a promising result in a country where more than 20% of the adult population is illiterate. On the other hand, these messages had another, more unexpected effect: in a survey conducted several months after the election, we observed that citizens who received these messages had lower levels of trust in their electoral institutions.

Election day in Uganda – 18 February 2016. © The Commonwealth, CC BY-NC 2.0

We explain this result by the fact that the messages increased the salience of the election for voters, while sending potentially ambiguous signals about the transparency and administrative capacity of the Commission. Once confronted with the reality of the election and the logistical difficulties observed on the ground, voters were able to interpret the content of these messages in a different way. Our study therefore highlights the benefits of an information campaign of this type, while showing the importance of the content of the messages: any information about a “sensitive” electoral process can give rise to potentially contradictory interpretations, which will affect citizens’ trust in their democratic institutions in the long term.Using a randomised evaluation, we were able to show that these messages had increased voter turnout, which is a major challenge in a country where more than 20% of the adult population is illiterate. On the other hand, these messages had another, more unexpected effect: in a survey conducted several months after the election, we observed that citizens who received these messages had a lower level of trust in their electoral institutions.

You have also studied the relationship of Muslim institutions to society and politics in Indonesia, and have highlighted the importance of land reform in this relationship. How do you explain this?

B.M. – This work was part of a broader research agenda exploring the relationship between the Indonesian state and Islamic organisations since 1945. Indonesia has approximately 225 million Muslim citizens, making it the largest Muslim country in the world.

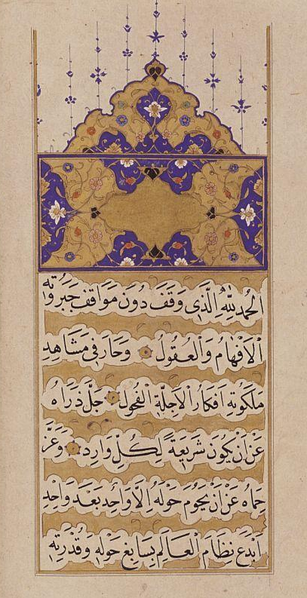

Endowment Charter (Waqfiyya) of Haseki Hürrem Sultan, 16th century ©Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts. Public domain

In this case, the purpose of this first study was to investigate the effects of an agrarian reform initiated by the Indonesian government in 1960, and that ended in resounding failure. This work revealed the decisive role of Islamic institutions in the failure of this reform. We showed that an institution of Islamic law called waqf (known in French as biens de mainmorte or habous in North Africa) allowed large landowners to eschew the redistribution of their farmland. The waqf is an original legal status based on a donation made in perpetuity for the purpose of financing a work of public or religious utility. For example, a landowner can endow his land as waqf by stipulating that the land will be used to finance an Islamic school. A property benefiting from waqf status cannot be subject to expropriation and its purpose cannot be changed after the deed of foundation. This institution has historically played an important – and probably negative – role in the economic development of certain regions, particularly in the Ottoman Empire.

Under pressure from Islamic organisations, the Indonesian government of the time had accepted the fact that land with waqf status could not be subject to the redistribution law. This legal obstacle greatly contributed to the failure of land reform. Indeed, landowners massively transferred their land to waqf status to escape redistribution. We show that these transfers led to a strengthening of local Islamic institutions, especially in the educational sphere. A large number of Islamic boarding schools (known in Indonesia as pesantren) are financed by waqfs, and many of these institutions play an important role in local political life. We argue that land transfers to waqf status in the 1960s had a lasting effect on support for political Islam. Today, Islamist parties (which remain a minority nationwide) garner most votes in the regions that should have been most affected by land redistribution. These regions are also adopting more local laws based on Islamic law (Sharia). Land reform has thus enduringly shaped the trajectory of political Islam in Indonesia, due to the mediating role played by the waqf.

© Shutterstock

We are currently working on a second study that focuses more specifically on the role of Islamic schools. This article shows how Islamic schools have adapted to the growth of public education since the 1970s. We also study the ideological consequences of the competition between public and Islamic schools(4)Islam and the State: Religious Education in the Age of Mass Schooling, Benjamin Marx, Samuel Bazzi and Masyhur Hilmy, NBER Working Paper, May 2020...

You have also studied corruption phenomena related to obtaining housing in slums and the issue of slums in general. What have you learned about this topic?

B.M. -My colleagues and I learned a lot over the course of this project. I’ll give you two examples.

First, the fact that slums in developing countries are not areas of lawlessness, as they are often described. Slums have a complex system of informal regulations and a dynamic housing market. In Kibera, Nairobi’s largest slum and one of the largest slums in Africa, 92% of residents pay a monthly rent. This market is dominated by powerful local political actors who have the power to intercede on behalf of landlords or tenants in conflicts over land use.

Kibera Electronics © neajjean, CC BY-SA 2.0

Another key takeaway is that the fundamental question raised by slums is the question of social mobility. Is life in the slums a stepping stone towards a better life, integrated in the metropolis, with greater access to public services and better jobs? Or, conversely, do slums create conditions for “poverty traps” to emerge, with residents remaining prisoners of their precarious living conditions from one generation to the next?

Paradoxically, most economists have a very optimistic view of slums: since living standards are generally much higher in urban areas, many people think that slums are a springboard for rural-urban migrants, who get closer to the opportunities offered by the city. However our understanding of these mechanisms is relatively limited in practice. Few long-term longitudinal studies have been carried out to understand whether there is real mobility from the slums to the urban middle classes and the formal sector. In our study of Kibera, we show that half of the residents live in the slum for more than eight years. This may lead to a less optimistic perspective on the phenomenon. To answer these questions, we will need to continue to follow the families who responded to our survey in 2012-13, in order to better understand whether the social mobility of residents of slums such as Kibera is a myth or a reality.

Can your research findings give rise to exchanges with politicians and/or citizens in the studied fields, particularly to consider solutions?

Uganda : elections 2016 © with courtesy of Pascale C. France. All rights reserved

B.M. – Of course! All this research aims to help governments, civil society, and citizens to better understand how to improve the governance and transparency of their institutions, how to promote political participation, and so on. Several of the aforementioned studies were carried out in partnership with local actors. For example, the study conducted in Uganda aimed to assess the impact of an information campaign on vote buying conducted by 13 local civil society organisations . This coalition of NGOs had contacted us in 2015 to implement a randomised evaluation of their operations. The study in Kenya was also a collaboration with the government, as I mentioned earlier.

Finally, I have been working for several months on the implementation of a project on decentralisation with the government of Indonesia and the World Bank. The purpose of this study is to enable Indonesian villages to better spend the funds they receive from the central government (which have been growing sharply since 2014) by improving village governance villages. It also aims to train municipalities on issues of local democracy and accountability. This project will allow us to apply what we have learned from other recent studies on decentralisation in Indonesia and other emerging countries. These countries are often ahead of us in terms of evaluation policies: in Indonesia, but also in India, South Africa, and Brazil (until recently) there is a real interest in collaborations between governments and researchers to evaluate and better understand the effects of a program or public policy.

Interview by Hélène Naudet, office of the VP for Research

Translated by Carolyn Avery

Benjamin Marx is Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at Sciences Po. His research focuses on the political economy of developing countries. In particular, he studies issues related to institutions, governance and electoral behavior.

Notes

| ↑1 | Eat Widely, Vote Wisely? Lessons from a Campaign Against Vote Buying in Uganda Benjamin Marx, Chris Blattman, Horacio Larreguy and Otis Reid, NBER Working Paper, September 2019. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Institutional Foundations of Religious Politics: Evidence from Indonesia, Benjamin Marx, Samuel Bazzi and Gabriel Koehler-Derrick, Quarterly Journal of Economics, May 2020. |

| ↑3 | Stelios Michalopoulos and Elias Papaioannou, Pre-colonial Ethnic Institutions and Contemporary African Development, Econometrica, January 2013. |

| ↑4 | Islam and the State: Religious Education in the Age of Mass Schooling, Benjamin Marx, Samuel Bazzi and Masyhur Hilmy, NBER Working Paper, May 2020. |